Many of us have been fortunate to have a mentor or two during our training. I have been blessed with four of them: Paul Chandler and Morton Grant taught me the finer points of glaucoma; Tom Hutchinson taught me the finer points of surgery and the practice of glaucoma; and Trygve Gundersen taught me the finer points of enjoying life and how to balance work with leisure.

As a first-year resident at Massachusetts Eye and Ear (MEEI) in 1972, I assisted staff ophthalmologists in their surgery. Dr. Gundersen was already slowing his surgical practice; at that time, he and Dr. Paul Chandler were the only surgeons who still scrubbed their hands with Betadine, shunned surgical gloves and wore their surgical masks beneath their noses.

While assisting with the few Graefe section cataract surgeries that I was privileged to be part of, Dr. Gundersen regaled the operating staff with tales of his yearly fishing trips to the Laerdal River in Norway. Between the third and fourth year of medical school at Yale, I had taken a research fellowship in Copenhagen and traveled extensively in Scandinavia. As a rank amateur fly fisherman, I knew about this legendary Laerdal River where the King of Norway fished; I then brazenly spoke up and expressed a desire to one day fish that river. Thereafter, Dr. Gundersen took me under his wing and became a second father to me and my family.

July, 1982, on Rangeley Lake, Dr. Gundersen teaching

my oldest son Andy the finer points of fishing

I have many wonderful memories of time shared with Dr. Gundersen, but a few stand out of his exceptional joie de vivre. No dinner could start without the requisite martini; my wife and I had our first martini at the Gundersen home. To this day, it remains our favorite cocktail and I cannot have one without thinking of Tryg.

He was a member of the Explorer Club of NY and shared the story of how he brought back a large piece of iceberg from a Norwegian fjord and served chunks of it in cocktails before one of their dinners. Because air had been compressed within the iceberg over hundreds of years, as the piece of iceberg melted, the air was released and tiny ancient bubbles rose through the cocktail. Even the extremely well-traveled Explorer members had never experienced this before.

He had exquisite taste in wine and food, and as a prominent physician, whom patients loved, he received many gifts of wines, which he gladly shared. Going to his house or going out to eat, there would always be three bottles of wine on his fireplace mantel, and he would ask me to choose one to have that evening. There were never any didactic lectures on wines but during the meal, in casual conversation about what we were drinking, he passed on his knowledge of wines.

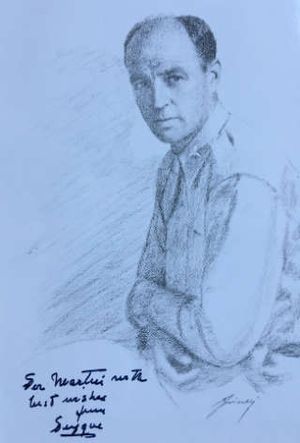

Sketch of Dr. Gundersen when he was

Lt. Colonel during World War II

He had a compound in Rangeley, Maine, where he built a main house and a cabin for family and friends. We were privileged to visit a number of times. Besides being on Rangeley Lake, he had also built two large ponds which he stocked with trout that he caught from Rangeley Lake and then carried in buckets to these ponds. Knowing of my budding interest in fly fishing, he invited my family to visit him there.

That first morning we went fishing; I set up my inexpensive beginner’s fiberglass rod and with the first cast, half of the rod flew into the water. I gamely, but weakly, tried to explain that it was a cheap rod and that might explain what happened. Without any hint of criticism, he asked to try the rod. He then proceeded to make the rod sing and the line gracefully floated out 30 feet. He agreed that it was not a great fly rod, but explained that much more important than the rod is getting the timing right. At this point, he put the rod down, pulled out about 35 feet of line, and proceeded to cast the line, without using the rod, out 30 feet. I learned then to never blame poor equipment in any endeavor.

Dr. Gundersen was a raconteur par excellence, and, if it involved him, he always made light of himself. One classic example is his recounting his 1962 award of the Royal Order of Saint Olav, established in 1847 by the then King of Norway and Sweden, “to reward individuals for remarkable accomplishments on behalf of the country and humanity.” He went to Oslo to receive this award and had a 15-minute audience with King Olaf. Apparently, the king was a man of few words and it was an extremely strained and seemingly endless “conversation.” Finally, Dr. Gundersen said to the King, “I want to thank you for this honor you have bestowed upon me — this Cross of St. Olaf. I don’t feel that it was in any way deserved.” As Dr. Gundersen then recounted, the king then said, “Vell, that sometimes happens.”

NEOS Gundersen Festscrift in March 31, 1985,

with Harriet and Tygve Gundersen and Martin and Karen Wand

But, it needs to be mentioned that Dr. Gundersen was also an astute observer, inquisitive researcher, and a surgical innovator. He published 30 journal articles as the senior author and developed the Gundersen flap, which saved many eyes before the advent of newer techniques to save a globe from perforating. If the war had not disrupted his academic career, he undoubtedly would have continued with great success at Harvard. Instead, he established a stellar reputation as an ophthalmic surgeon with patients coming from around the world to see him.

One notable patient was King Saud of Saudi Arabia. The king first learned of Dr. Gundersen because Dr. Gundersen had spent most of his World War II time in charge of the 80 hospitals in the Mediterranean Theater. When the king needed cataract surgery, he flew to Boston with “his 10 sons, 10 concubines and 4 wives on two 707 jets, and they took over a whole floor of the Brigham Hospital.” His entourage included “a cadre of military people with machine guns and our whole FBI was up here in force.” Needless to say, the surgery went very well and before the king left, everyone who came into contact with him at the Brigham received a gold watch.

Dr. Gundersen died at age 85 on Feb. 25, 1987. He was an exceptional physician and surgeon, an extraordinarily charming bon vivant, and a most generous friend; his life lessons will not be forgotten.