For a long time, I thought about writing an article on Russian ophthalmologist, Svyatoslav “Slava” Nikolayevich Fyodorov, MD but was uncertain how to approach a topic about the early days of refractive surgery.

Should it be a tribute to Dr. Fyodorov, who reinvigorated radial keratotomy from the earlier work by Sato? Should I report on my initial exposure to radial keratotomy in Moscow? Should it be about the formation of the Prospective Evaluation of Radial Keratotomy (PERK) study? Or should I include all of that?

Today, the impetus for me to sit down and finally tackle this project is the recent American withdrawal from Afghanistan.

I arrived in Moscow on Jan. 24,1980. I had been personally invited by Dr. Fyodorov and more formally through an invitation by the Ministry of Health. Four days earlier, then President Jimmy Carter proposed that the summer Olympics be moved from Moscow if the Soviet Union did not remove its troops from Afghanistan.

Two months later, on March 21, President Carter pulled the United States Olympic Team from the Moscow Olympics in a boycott, along with 64 other nations . Forty-one years later, although in a different context, Afghanistan’s domestic problems are still being played out on the world stage.

Dr. Fyodorov was a visiting professor in New York during my residency and was active in teaching IOL implantation of the Sputnik lens after intracapsular cataract extraction. Many of us had the opportunity to spend time with him and learn his implantation technique. In subsequent years he was a frequent visitor to New York where several equestrian shops became his usual haunts. It was during one of these visits that he suggested I visit with him to learn to the radial keratotomy procedure and to examine post-radial keratotomy patients, both recent and long-standing. By that time several thousand patients already had radial keratotomy performed in Moscow.

Radial keratotomy had been introduced into the United States by Dr. Leo Bores, who had spent time in Moscow with Dr. Fyodorov. Several other U.S. ophthalmologists were also engaged in either learning about or already performing radial keratotomy. Fyodorov was interested in developing a surgical procedure to treat myopia and modified an earlier Japanese technique that created incisions into both the epithelial and endothelial corneal layers. Professor Tsutomu Sato working at the Research Institute of Ophthalmology of the Juntendo University School of Medicine did this surgery in animal models and then performed human clinical studies. In his 1953 American Journal of Ophthalmology publication, he stated, “This new surgical approach to myopia (anterior and posterior half-corneal incisions) is a proven, safe method which definitely cures or adequately alleviates over 95% of all cases of myopia in Japan.” As we learned later, virtually all these eyes developed corneal decompensation because of endothelial damage. Dr. Fyodorov was undaunted by this prior unfavorable experience. He believed that there was a surgical solution for myopia.

Although his major emphasis was on a corneal approach to the condition, members of his department and others in Russia were also investigating methods to strengthen the posterior sclera in cases of high myopia. Dr. Fyodorov’s approach used anterior incisions into the “peripheral circular ligament of the cornea” to reshape the cornea. These incisions would produce peripheral corneal bulging and central corneal flattening to reduce the myopic refractive error. Many ophthalmologists were skeptical of his reported results. I firmly believe that Dr. Fyodorov’s persistence, dynamism and positive drive were responsible for the ultimate acceptance of radial keratotomy.

My two week stay in Moscow was professionally, culturally and socially enlightening. From the moment I was met at Sheremetyev Airport, where Dr. Fyodorov plopped a fur hat on my head while telling me that one loses 40% of body heat through the scalp, until my last morning in Moscow having breakfast in his apartment, I was awed by the complexity of this man. I learned that a ranking member of the Communist Party lived a completely different life than the citizen who waited in line for hours to buy food and clothing.

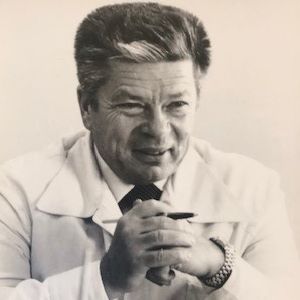

Svyatoslav “Slava” Nikolayevich Fyodorov, MD

Dr. Fyodorov used my visit to permit key members of his staff to invite me into their homes for dinner. They did not have to wait in line for food or beverages since they were entertaining a person invited by the Ministry of Health. I watched him bolster the confidence of one of his students, who was defending his doctoral thesis. This young man was being badgered by a professor, who was not favorably disposed to Dr. Fyodorov and his rise in the international ophthalmic community. As it was ultimately explained to me, Dr. Fyodorov told the professor that he should only be critical of a student’s work and not the institution where it was performed. He did not accept the ad hominem nature of this criticism.

A large shipment of equipment was delivered to the new eye institute Dr. Fyodorov was building. When I was there only two of the three buildings were functional. As an instrument shipment from Zeiss Jena was being unloaded from one truck, the crates and their insulating materials were being loaded onto another truck. I paid no attention to this at the time since I was so impressed with the quality and quantity of the instruments and questioned to myself who was paying for all this equipment.

Several days later, I was invited to Dr. Fyodorov’s dacha (a country home). Adjoining this area, filled with small weekend retreats for the Soviet elite, was a peasant village and small farm. It was here that Dr. Fyodorov kept his horses. As we walked into the barn, I was amazed to see Zeiss Jena crating and insulating materials filling many of the openings and crevices in the walls of the barn near his beloved horses. He was never one to permit the waste of resources, no matter how trivial, in a social environment where even small things were precious.

Dr. Fyodorov was a fair yet demanding boss. The people working for him were equally dedicated to creating a world-class eye institute. Dr. Valery Durnev was one of the young ophthalmologists who did the major work on astigmatic keratotomy. He reviewed most of the long-term patients with me as I examined them. He related how the radial keratotomy procedure had evolved from earlier techniques using only peripheral incisions that did not have a lasting effect, to those that were now being used that considered the depth and length of the incisions. My lasting memory of him was sharing cognac and chocolates and speaking about inviting him to visit the U.S. Sadly, his young life ended in a tragic accident a year later.

So, I returned to New York excited about the prospect of performing radial keratotomy surgery if I could get it approved by Mount Sinai Hospital. Then a strange thing happened. I received a call from Dr. George Waring, who I had known only casually from scientific meetings and in his role as an editor on Survey of Ophthalmology. He had learned that I had visited Dr. Fyodorov and wanted to hear about my experience. He also asked if I could reach out to Dr. Fyodorov to extend him an invitation. I told him I would contact Dr. Fyodorov but that I could not guarantee success. I also suggested that he might consider visiting Dr. Fyodorov on his own, since several American ophthalmologists appeared in his clinic, uninvited, while I was there. Dr. Waring did visit Dr. Fyodorov by invitation.

Then in March, I received an invitation from Dr. Waring to attend a meeting at Hartsfield International Airport in Atlanta. The purpose of the meeting was to explore the prospect for a research study of radial keratotomy. It was attended by ophthalmic surgeons and members of the National Eye Institute. This was the impetus for the PERK study that was later designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of this surgical procedure.

There were several reasons for studying radial keratotomy at that time that I presented at a Keratorefractive Society Meeting on Controversial Aspects of Radial Keratotomy in 1980. First, the procedure that Dr. Fyodorov had already made technical modifications from his initial procedure. Second, some of surgeons already performing radial keratotomy in the U.S. had further modified Dr. Fyodorov’s technique.

Third, we wanted a better understanding of how incising the cornea reduced myopia — how the number, length and depth of incisions influenced the effect. Fourth, we wanted to learn why some myopic eyes fared better than others. Finally, we wanted to learn all the variables that could be influenced to make the procedure predictable. A large body of data reflecting a singular surgical approach was lacking and the PERK study sought to fill this gap.

PERK also afforded me the opportunity to serve as a spokesperson to promote the study and to be interviewed by journalist Diane Sawyer and newscaster Earl Ubell (who also observed surgery) on local New York TV stations and on the nationally broadcast Phil Donahue Show. The Atlanta meeting also had an unintended consequence. Many of those who attended that meeting were ultimately sued for restraint of trade.

But that’s a story for another time.