Senior ophthalmologists share the best of what they’re reading this Spring. Share what you’re reading and send your review to scope@aao.org.

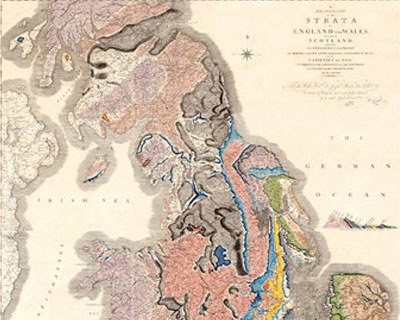

The Map That Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology

By Simon Winchester

Reviewed by Alfredo A. Sadun, MD, PhD

In this edition of Scope, you will read about Dr. Robert Tibolt’s avocation of mapmaking. I was immediately drawn to Dr. Tibolt’s work having previously read Winchester’s remarkable story of W. Smith.

Smith was an unpretentious, non-academic whose map of England showed data, but more importantly, perspective, on our planet, its geological processes, its time scale and even inklings on biological evolution five decades before Charles Darwin.

Winchester, a remarkably lucid writer, begins with the excellent biography of William “Strata” Smith. Smith’s education ended at age 11, but he taught himself as an apprentice to be a surveyor. His job involved overseeing the digging of a canal for the newly lucrative business of finding and transporting coal. This was a quarter-century after the discovery of the steam engine and the unearthing in England of vast amounts of the original black gold: coal.

Finding, extracting, and moving coal became the basis of the industrial revolution and prompted great economic growth in England. In 1793, at the age of about 23, Smith had the epiphany that there existed geological strata. Smith figured this out from his hobby of fossil collecting. He transformed his house into a fossil museum and kept himself in debt by buying larger houses to accommodate his growing collections. But this allowed him to recognize that there were patterns of animal and plant fossils which lay in specific layers of rocks. Intriguingly, these layers did not parallel the surface.

Smith began analyzing this locally, then across England. He envisioned, for the first time, a 3-D map of the world. He charted the unknown underside of the earth which initially allowed for the discovery of new coal veins. Then, more importantly, he revealed the truth of the ancient processes of geology. The earth was old. That challenged the bible and opened space in many sciences. Crossing England from east to west meant traveling backwards, thousands of years of geological time for every yard.

Ultimately, Smith spent over 20 years creating an amazing hand-painted map. Personally, it caused him no end of troubles. He was initially not understood and ultimately vilified by jealous contemporaries and academics. He was rejected by the scientific establishment and went to debtors' prison. But the map survived and changed the way we saw the world. It now rests in the lobby of the Geological Society, ironic as Smith himself was denied entry.

As Dr. Tibolt’s story retells, maps are effective ways to convey a lot of facts through images, but they are also a means of seeing things a different way. They are portals to national interests, cultures and the planet itself. Winchester made these points brilliantly.

The 3D Map

Three Simple Lines: A Writer’s Pilgrimage into the Heart and Homeland of Haiku

By Natalie Goldberg

Reviewed by J. Kemper Campbell, MD

Natalie Goldberg’s brief book, “Three Simple Lines,” is a wonderful introduction to the haiku.

A septuagenarian, Goldberg’s life has been seasoned by a bout of cancer and her longtime study of Zen philosophy. She teaches creative writing and has now published her 15th book. This one unfolds like a haiku, simply and succinctly with unexpected subtlety.

Each haiku is a three-line, unrhymed poem consisting of 17 syllables. Haiku entered the Japanese culture in the 17th century and later became popular in all languages. Goldberg was introduced to its four classic practitioners by the American Beat poet Allen Ginsberg. Her book is a tribute to the four Japanese poets, Basho, Busan, Issa, and Shiki, who originated the form as well as a travelogue of her visits to Japan and a personal memoir.

The book succeeds in all three areas. The history of haiku’s development is fascinating. Her descriptions of modern Japan will transport readers across the sea and her memoir will remind readers that classifications by age, gender, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, and race dissolve within the world of haiku.

Although in English the haiku traditionally consists of a 5-7-5 division of syllables, translations of the Japanese poets seldom adhere to this pattern. Multiple examples show that a pure haiku should involve a commonplace subject, often rooted in nature, which should result, according to Ginsberg in the mind experiencing “a small sensation of space which is nothing less than God”.

Goldberg uses multiple translations of Basho’s iconic haiku to illustrate this point:

At the ancient pond

a frog plunges into

the sound of water

Finally, the book should inspire any reader to compose his or her own haiku such as the reviewer’s example:

Howling winds drift snow

Coffee cools as pages turn

Dogs and tulips dream

Neanderthals Rediscovered: How Modern Science is Rewriting Their Story

By Dimitra Papagianni and Michael Morse

Reviewed by Thomas S. Harbin, MD, MBA

Most of us know by now that we all carry Neanderthal genes, and I suspect most of us conjure up the stereotypical image of a Neanderthal as a highly muscled caveman with a brutish skull and very limited capabilities.

This book will change your mind. Neanderthals buried their dead, cared for their sick, hunted large animals and had some degree of a spoken language. They had many more abilities including the use of fire, clothing, and medicinal plants, to name just a few. The authors provide up-to-date archeological details and a complete chronology of these closest of our hominid cousins comparing them to species such as Homo erectus and H. heidelbergensis. They, like us modern humans, evolved over many thousands of years and spread into Asia and Siberia. Modern humans may have caused their ultimate extinction, and we get all the evidence and thinking in this book.

If you want a good discussion of this subject and an overview of human evolution, this is the book for you.

Apollo’s Arrow: The Profound and Enduring Impact of Coronavirus on the Way We Live

By Nicholas A. Christakis

Reviewed by John R. Stechschulte, MD

Written between March and August 2020, Nicholas A. Christakis describes the known and unknown elements of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a physician and sociologist, he presents the biological, clinical, epidemiological, social, economic and political impacts and the likely long-term outcomes of this plague.

Christakis writes about the pandemic in such detail that this book could later serve as a compelling textbook for medical students to understand this plague and how it compared to those going back a few thousand years.

With his careful analysis and use of modern research, the reader is left with hope that we will recover over the next couple of years or sooner, as he anticipated, thanks to the rapid development of vaccines. He was expecting powerful vaccines because “the biology of the coronavirus is less daunting than even that of the common flu.”

This book chronicles the circulation of the coronavirus in China during December 2019, the stroke of luck that led to the diagnosis of America’s “patient zero” in Snohomish, Wash. and how Christakis’s personal contact with his Chinese colleagues on Jan. 24, 2020 led him to redirect his research and studies.

The author states that this coronavirus is a moderately contagious and a moderately lethal virus which is spread by asymptomatic patients making very early and drastic shutdowns crucial for significant reduction in worldwide deaths. Surprisingly, due to unrecognized early spread of this virus, halting international flights has had little or no impact on the pandemic. He does demonstrate the importance of widespread accurate viral testing which must be paired with intense contact tracing. Both efforts have been difficult to accomplish in the U.S. due to longstanding inadequate support for public health.

I found the book’s genetic description of this virus fascinating. Only 29,903 letters long, the SARS-CoV-2 virus is 96.2% identical to a bat coronavirus found years ago in China. The author says this “confirms” that SARS-CoV-2 originated in bats. By mapping the virus genome, it was determined that this virus undergoes a tiny mutation about every two weeks on average. Knowing this rate and the genomes found in specific U.S. cities, virologists were able to trace the timing and path of infections.

Surprisingly, the large outbreak in a Seattle nursing home and patient zero’s infection did not spawn other new variants or infect other individuals. Rather a later importation was to blame for the Washington outbreaks, and importation from Italy led to most of the outbreaks in New York. This book covered many of the social, economic, and political aspects of COVID-19. Not surprisingly, these aspects resemble the problems that were encountered in many past plagues. Christakis ends the book describing the hope we all have that the world will handle the next pandemic (no matter how soon that could arrive) with greater preparedness, and less fear and denial.

Bonus: Podcast Series – The Rewatchables

Reviewed by John R. Stechschulte, MD

www.theringer.com/21445741/the-rewatchables-podcast-complete-episode-archive

Dr. Masket recently recommended this podcast to me. He is a movie buff, I would say an expert, and seriously enjoys the great classic movies, like The Godfather. Most of us watch movies a second time and maybe many of us watch some movies over and over. Who has not used a quote more than once from their favorite movie? “I’m going to make him an offer he can’t refuse.” The Rewatchables podcast began in 2015, when Bill Simmons and Chris Ryan produced the first of what is now over 150 episodes. The Ringer staff “remember, celebrate and meticulously dissect the movies that we just can’t stop watching.” Visit this website to search for your favorite movie, then listen to learn more about what makes great movies so enjoyable.

Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions

By Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths

Reviewed by Alfredo A. Sadun, MD, PhD

I loved this book. They had me by chapter 3 (sorting) when I read that most filing systems invest too much effort into the filing.

Neatness and many forms of over sorting are not optimal. Insofar as the last item filed has the greatest likelihood of being needed in the future, stacking things as, “Last in” equals “First out” make sense. And for me, that means legitimizing the vertical stack of papers on my desk where the top is the most likely place to find what I need next.

It was delightful to appreciate that a messy garage is a formal algorithm for filing, and that we are always making and using other types of algorithms in daily living. When do you take the next parking space or stop looking for a new apartment (stopping strategy originally formulated on finding a spouse)? When do you invest in exploration and when do you exploit your knowledge (such as trying new restaurants or revisiting the tried and true)? How should you schedule priorities (Easy things first? Important things? Urgent things? A sampling of all?). How can using randomness improve the outcome of calculations? These things can be mathematically expressed.

However, no formal training in mathematics is required to understand the authors’ lucid thinking. They employ simple terms and use examples of common human behavior as well as addressing new technologies and methodologies.

They did a brilliant job discussing one of my favorite concepts that I think is necessary to evaluate a patient’s lab tests. It is true that they justified the approach by evoking La Place’s Law and Bayes’ Rule, but their take-home message of considering the pretest probability is crucial for all physicians.

These mathematical tools give us a lot of power to predict the future and to utilize and analyze the right tests. I wish more physicians understood this and the concept of why NOT getting a test (such as an MRI or a mammogram) is smarter when the suspicion for disease is low. I learned a lot about the limits of analysis with or without computers when considering the concept of overfitting. No wonder big data can mislead. I’m now going to use relaxation strategies in a lot of my thinking. You will be astounded by the shortcuts and heuristics in thinking strategies that this book allows. Or you will be astounded by the common errors in analysis that we commonly accept.

Having heard this on audible, I bought the paperback and have often gone back and referred to the effective simple graphs. In short, the book was about optimizing strategies, and I will require it as reading for those doing doctoral work in my lab.

The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft and the Golden Age of Journalism

By Doris Kearns Goodwin

Reviewed by Samuel Masket, MD

Doris Kearns Goodwin provides us with a most unusual and intense biography in that it encompasses much of the life of two rather than one U.S. presidents, both significant American historical figures.

Among the remarkable facets of both of their lives is the power, intelligence, and level of education of the women in their backgrounds who, to my sense, afforded both great developmental advantage.

We come to learn much about social, economic, and cultural reform in the U.S. under Theodore Roosevelt’s leadership, stimulated initially by his friendship with Jacob Riis during Roosevelt’s time in New York and brought to light by other journalists, led by Ida Tarbell, who led a movement that came to be known as the Muckrakers; among other things they helped shed negative light on the ultra-wealthy “robber barons” of the day.

We also become witness to great personal tragedy with Roosevelt experiencing the deaths of his mother and wife on the very same day. William Howard Taft too suffered personal tragedy as his beloved wife Nellie suffered a serious stroke in the early months of his presidency and would not fully recover her faculties.

But truly the main thrust of the book is the relationship between these two men who would both become president. As the senior of the two, Roosevelt groomed Taft to succeed him, asked much of him and occasionally disappointed him with undesirable appointments. But Taft was dutiful and accepted his fate.

Eventually he was Roosevelt’s choice as successor in 1908 when Roosevelt declined to run, having already served seven years, the first three when President McKinley was assassinated, and then elected to a four-year term in 1904. Upon leaving office in 1908, Roosevelt was arguably the most popular president in history and quite likely could have remained so. However, he sorely missed the “bully pulpit” and returned from adventures abroad to challenge Taft’s reelection bid in 1912.

Roosevelt, driven by ego, heavily denigrated his former friend and protege, split the Republican ticket as he formed the Bull Moose Party, and assured the election of Democrat Woodrow Wilson, altering the course of history.

The book is by necessity voluminous, as Kearns Goodwin’s research is impeccable and beyond comprehensive. There is so much to be learned.