William Richard “Dick” Green spent his nearly 40-year career directing the Wilmer Eye Institute of Johns Hopkins Hospital, where he gained renown as one of the foremost eye pathologists of the 20th century. But his beginnings were modest.

Dr. Green grew up in Paducah, Ky., where he was the youngest of eight children. He had several jobs as a child and teenager, including a paper route, working as a short order cook and a laundry service and caddying at a country club. He played trombone in a high school band and was on his high school basketball team. He sang tenor at his church.

While attending Centre College in Kentucky, Dr. Green met his future wife, Janet Jones, and directed a band. After graduating in 1955, he attended medical school at the University of Louisville. In medical school he met Arthur Keeney, MD, who was influential in Dr. Green’s career and undoubtedly encouraged Dr. Green to pursue ophthalmology.

After graduation from medical school, Dr. Green completed an internship at the New England Medical Hospital of Tufts University, attended postgraduate courses in ophthalmology at Harvard, the Howe Lab and the Retina Foundation in Boston. He then completed a two-year ophthalmology residency at the Wills Eye Hospital and was a postgraduate student at the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness (there was no National Eye Institute at the time). He then did a fellowship at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) under the direction of Academy Laureate Award Recipient, Lorenz Zimmerman, MD. To top off his training, Dr. Green did a residency in anatomic pathology at Temple University and became board-certified in both ophthalmology and anatomic pathology.

Dr. Green spent a year heading the ophthalmic pathology laboratory at Wills and in 1968 became the director of the ophthalmic pathology laboratory at the Wilmer Eye Institute of Johns Hopkins Hospital. He had a forthright personality, a sound character, eschewed speculation and was not shy about making his opinions known. He maintained fidelity to these qualities in both his personal and professional life. He was not demure in the presence of almost anyone with the possible exception of Dr. Zimmerman. With that in mind, he was not afraid to disagree at times with the famous director of the Wilmer Institute, Edward Maumenee, MD, during grand rounds. This led to lively debates about various ocular conditions. I’m sure Professor Maumenee enjoyed and learned from these encounters.

Dr. Richard "Dick" Green and his wife Janet at Dr. Green's graduation from the University of Louisville School of Medicine.

Larger than life in every aspect, Dr. Green tackled his profession and personal life with gusto and enthusiasm. He was encyclopedic and made sure that his students were up to date on the current literature. Dr. Green was famous for carrying carousels of Kodachrome photos to his lectures and showing many examples of each condition he discussed. He authored over 700 articles in the peer reviewed literature and a number of book chapters.

Dr. Green’s best-known chapters were the extensive, state of the art chapters on the pathology of the retina and choroid in Spencer’s Ophthalmic Pathology, An Atlas and Textbook. These chapters remained the standard references for many years. He was the king of clinicopathologic correlations and his publications were cited for many years as the definitive articles about the pathology of virtually all diseases of the eye.

During his career, Dr. Green essentially accumulated his own dataset of eye pathology cases and he interrogated that dataset. He was in a unique position to do that as he was at the Wilmer Institute. The clinical tools at the time included fundus photography and fluorescein angiography. He used the pathology tools at the time, light microscopy and electron microscopy, to correlate the pathologic findings with the clinical findings in his large collection of cases. This better enabled understanding of many ocular conditions, including age-related macular degeneration and other retinal diseases.

Few had the capacity and tenacity to do this since Ernst Fuchs of Vienna who, in the early part of the 20th century, correlated fundus findings using the ophthalmoscope with light microscopic findings from his own large collection of enucleated eyes. In many ways, this was a metaphor for Dr. Green’s life-commitment, steadfastness and hard work.

Dr. Green taught at the microscope. He had twice-weekly sign-out sessions with medical students, residents, and fellows. Occasionally practicing ophthalmologists would attend these sessions. He would sit at a two-headed microscope. Others in the room would have their own microscopes and descriptions of the cases they worked up. They would take turns bringing their cases to Dr. Green at his microscope, which was perched on a small, flimsy table. If there was a slightest motion while both he and the student looked at the slides, Dr. Green would jump back from his microscope, cry out as if he were poked in the eyes and glare at the student. This was his method of controlling the process. Things never got out of hand; Dr. Green was always in control.

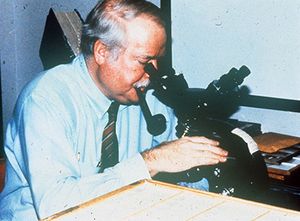

Dr. Richard "Dick" Green uses a microscope at the Wilmer Institute, Johns Hopkins Hospital.

At the time, Dr. Green was a voracious smoker, which was allowed in his laboratory. He would sometimes simultaneously have a lit cigarette and lit cigar in an ashtray while he also smoked his pipe. He usually had several cups of coffee during these sign-out sessions; he would press a button on the phone next to him, a beep would go off, and a technician would come in and fill up his coffee mug. Two beeps would summon his secretary, usually to modify a report or request some material. Dr. Green was a “gentle giant” who was kind and caring underneath his gruff outer coating. His fellows were most loyal to him and vice versa.

Dr. Green was a good cook. He would invite students and colleagues to his house, and either he or Janet would prepare a meal and enjoy it with his guests. I remember he introduced me to a true “Virginia ham”-one that is dried and salted. He also brought in dishes to the laboratory for his students.

One memorable meal with chili that Dr. Green made with chèvre (goat) meat. He enjoyed music and played the trombone in a band during his youth and was known as “Slide Bones Willie.” He would play music at the end of the day in his office; this could be classical music or country and western. I remember Dr. Green playing Willie Nelson songs. Dr. Green would sing to the music himself.

Dr. Green was a notable member of the American Ophthalmological Society (AOS) where he served as president and was awarded the Howe Medal. He would dance with his wife Janet after the annual AOS banquets. He was an avid traveler and would be invited to various venues around the world and travel with his wife. He and Janet enjoyed restaurants, conversation, sightseeing and music/dancing during the trips. Dr. Green and Janet raised two sons and, in later years, had three granddaughters.

Dr. Green’s legacy is his students. He taught the Wilmer residents for nearly 40 years with many fellows, and he was a great mentor and leader. The students learned that ophthalmology was more than cataract surgery: it was a branch of medicine and surgery. They learned to be honest, truthful, and ethical. These students took the life lessons of integrity, commitment and devotion that they learned from Dick Green with them throughout their professional and personal lives.

It is a testament to Dr. Green’s legacy that many of his students have become leaders in ophthalmology themselves.