EPIDEMIOLOGY

Global Information

- Worldwide, diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness among working-aged adults.

- Global burden of diabetic retinopathy: 93 million people

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy: 17 million

- Diabetic macular edema: 21 million

- Vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy: 28 million

- Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy is worldwide with only slight ethnic differences.

Region-Specific Information (Sub-Saharan Africa)

- Data is limited; see Table 1.

|

Table 1. Epidemiology Statistics for the African region

|

|

Prevalence of diabetes (in Nigeria)

|

4.7%

|

|

Blindness prevalence of diabetic retinopathy (in Nigeria)

|

0.5%

|

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/DEFINITION

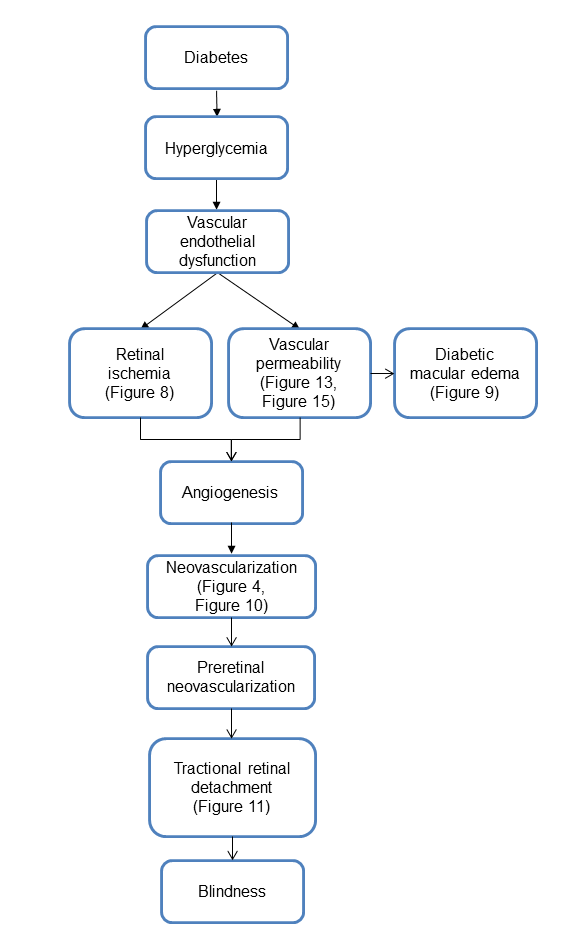

Chart 1. Pathophysiology. See Image Library for figures.

Risk Factors

- Blood glucose

- Duration of diabetes

- Blood pressure

- Blood lipids

- Renal impairment

- Pregnancy

SIGNS/SYMPTOMS

- Asymptomatic

- Decreased vision

- Floaters

- Metamorphopsia

- Symptoms of retinal detachment

- Examination findings consistent with pathophysiology (Chart 1)

MANAGEMENT

Classification

See Table 2.

|

Table 2. International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy Disease Severity Scale

|

|

Proposed Disease

Severity Level

|

Findings Observable Upon Dilated Ophthalmoscopy

|

|

No apparent retinopathy

|

No abnormalities

|

|

Mild NPDR

|

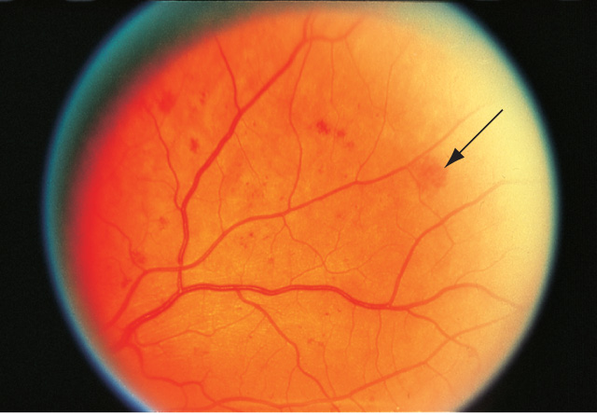

Microaneurysms only (Figure 13)

|

|

Moderate NPDR

|

More than just microaneurysms but less severe NPDR

|

|

Severe NPDR

|

Any of the following and no signs of proliferative retinopathy:

- More than 20 intraretinal hemorrhages in each of four quadrants

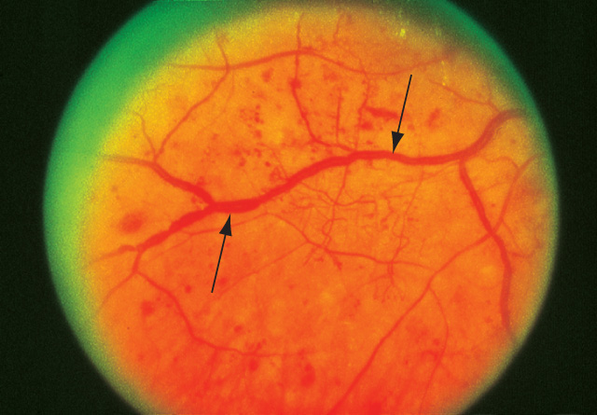

- Definite venous beading in 2 or more quadrants (Figure 14)

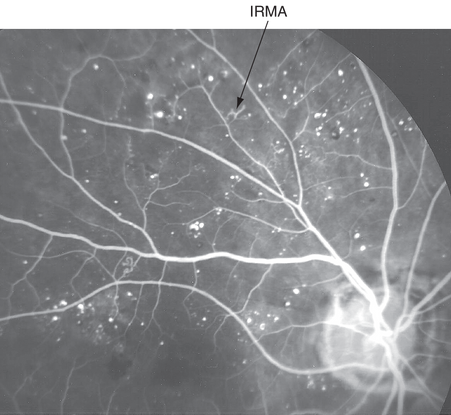

- Prominent IRMA in 1 or more quadrants (Figure 15)

|

|

PDR

|

One of both of the following:

|

IRMA = intraretinal microvascular abnormalities; NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Diabetic Retinopathy. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2008 (4th printing 2012). Available at: www.aao.org/ppp.

Treatment of Diabetic Macular Edema

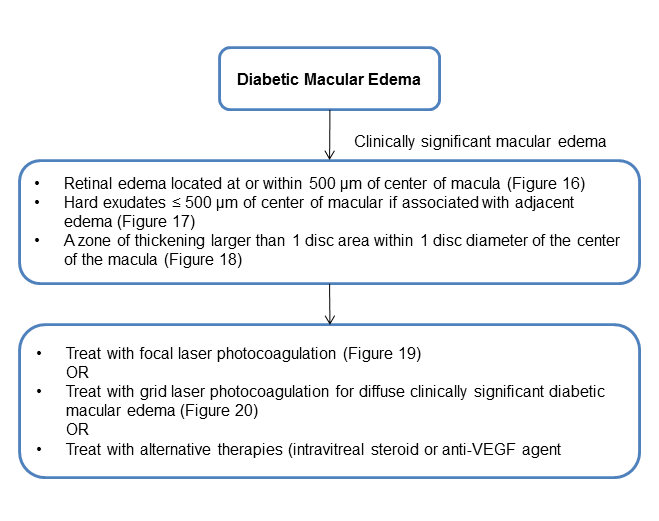

Chart 2. Treatment of diabetic macular edema. See Image Library for figures.

Management of Diabetic Retinopathy

See Table 3.

|

Table 3. Management Recommendations for Patients With Diabetes

|

|

Severity of Retinopathy

|

Presence of CSME

|

Follow-up (Months)

|

Panretinal Photocoagulation (Scatter) Laser

|

Fluorescein Angiography

|

Focal and/or Grid Laser

|

|

Normal or minimal NPDR

|

No

|

12

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Mild to moderate NPDR

|

No

|

6–12

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Yes

|

2–4

|

No

|

Usually

|

Usually

|

|

Severe NPDR

|

No

|

2–4

|

Sometimes

|

Rarely

|

No

|

|

Yes

|

2–4

|

Sometimes

|

Usually

|

Usually

|

|

Non–high-risk PDR

|

No

|

2–4

|

Sometimes

|

Rarely

|

No

|

|

Yes

|

2–4

|

Sometimes

|

Usually

|

Usually

|

|

High-risk PDR

|

No

|

2–4

|

Usually

|

Rarely

|

No

|

|

Yes

|

2–4

|

Usually

|

Usually

|

Usually

|

|

Inactive/

involuted PDR

|

No

|

6–12

|

No

|

No

|

Usually

|

|

Yes

|

2–4

|

No

|

Usually

|

Usually

|

CSME = clinically significant macular edema; NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Diabetic Retinopathy. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2008 (4th printing 2012). Available at: www.aao.org/ppp.

CASE STUDY

History of Present Illness

A 63-year-old patient had a history of diabetes and was on insulin therapy for more than 15 years. She was a poor historian with poor socioeconomic status. She complained of poor vision in both eyes for many years. She never had an eye examination before, and she was not aware of the recommendation for an annual eye exam. It was difficult for her to find transportation to seek eye care. She reported that her blood sugar is poorly controlled. She denied other eye complaints such as pain, flashing lights, floaters and tearing.

Past Medical History

Diabetes mellitus for 15 years

Examination

- Visual acuity: Able to count fingers at ½ meter both eyes

- Extraocular movements: Full

- Intraocular pressure: normal both eyes

- Mild ptosis LEFT eye from past trauma

- Cornea: clear both eyes

- Anterior chamber: quiet and formed, with no neovascularization of the iris

- Lens: dense posterior subcapsular cataract RIGHT eye (Figure 26) and nuclear sclerotic cataract +2 in the LEFT eye.

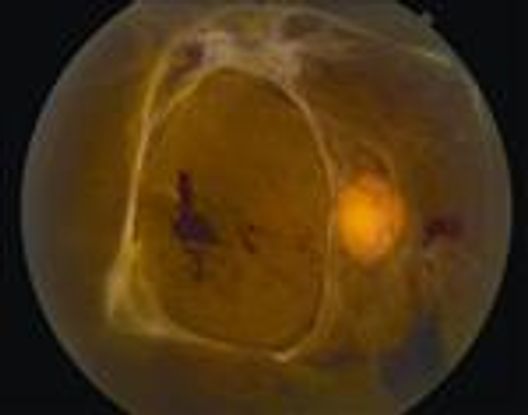

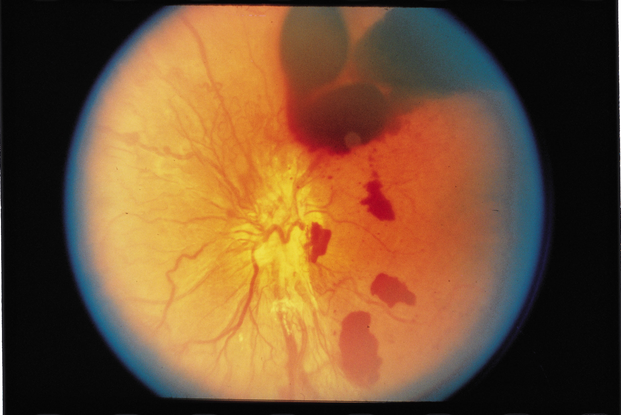

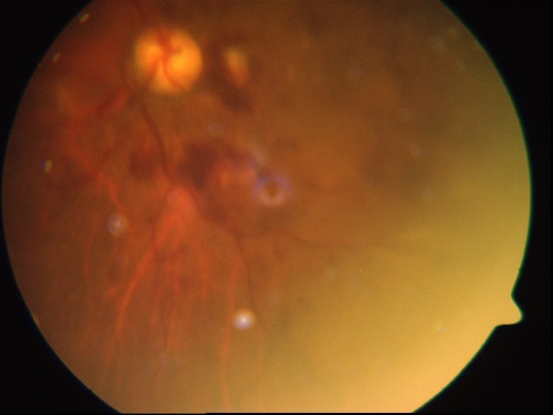

- RIGHT eye: hazy view but wide field contact lens fundoscopy revealed proliferative diabetic retinopathy with neovasularization of the disc and early fibrovascular membrane formation at the papillary area (Figure 27A).

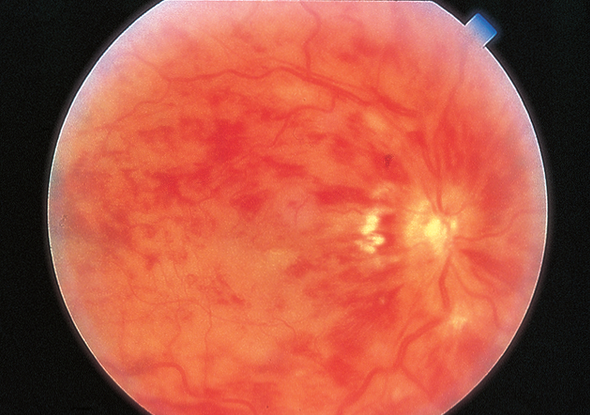

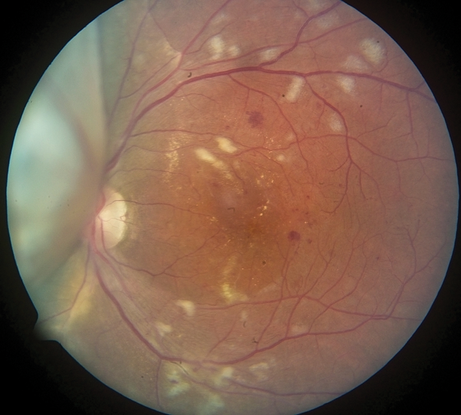

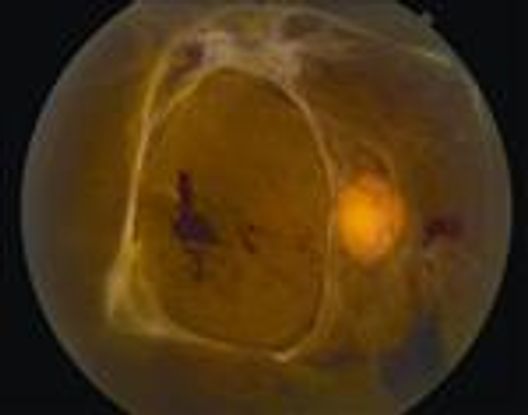

- LEFT eye: severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy with retinal hemorrhage in 3 quadrants of the retina including the macula (Figure 27B).

Treatment

- Recommended that the patient undergo panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) in both eyes followed by phacoemulsification and intraocular lens placement in the RIGHT eye.

- The patient underwent PRP in the RIGHT eye with power 700mW and only 500 shots were given before the patient refused further treatment due to pain. She refused any further treatment and an arrangement was made to speak to a relative at her next visit.

IMAGE LIBRARY

Differential Diagnosis

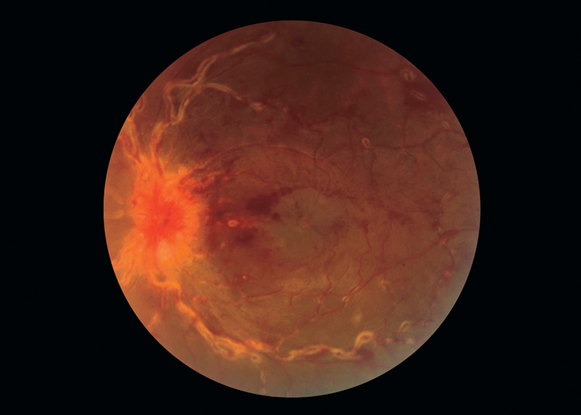

Figure 1. Hypertensive retinopathy. Note the disc edema, macular exudates, intraretinal hemorrhage with nerve fiber layer infarct, and venous congestion.

(© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 2. Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). CRVO in an eye with hand motions vision. The veins are dilated, and retinal hemorrhages are present. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 3. Branch retinal vein occlusion. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 4. Neovascularization of disc. (Reprinted from the Digital Reference of Ophthalmology, Retina and Vitreous, Retinal Vascular Disease, with permission from the Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology of Columbia University.)

Figure 5. Radiation retinopathy. Image of an eye that has undergone plaque brachytherapy for treatment of choroidal melanoma. The melanoma can be seen nasally, obscuring part of the disc. (Reproduced, with permission, from Schubert HD. Retina and Vitreous. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 12, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014. Courtesy of Tara A. McCannel, MD, PhD.)

Figure 6. Sickle cell retinopathy, with peripheral neovascularization (“sea fan” neovascularization) with autoinfarction. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 7. Sarcoidosis, with retinal vascular sheathing. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Pathophysiology/Definition

Figure 8. Cotton-wool spot (capillary retinal arteriole obstruction). (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

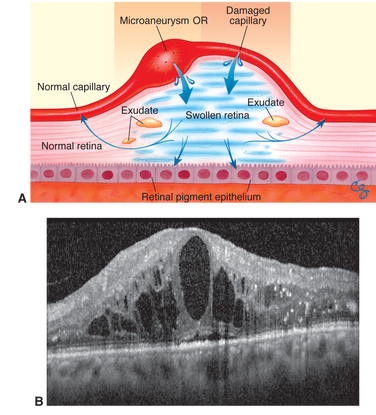

Figure 9. Diabetic macular edema. A.Mechanism of diabetic macular edema, demonstrating development of thickening from a breakdown of the blood–retinal barrier. B. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomogram of diabetic macular edema. Note the foveal detachment. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 10. Retinal neovascularization. (Image courtesy of Kellogg Eye Center, University of Michigan.)

Figure 11. Tractional retinal detachment. There is associated hemorrhage due to traction on fronds of neovascular ingrowth. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Management Classification

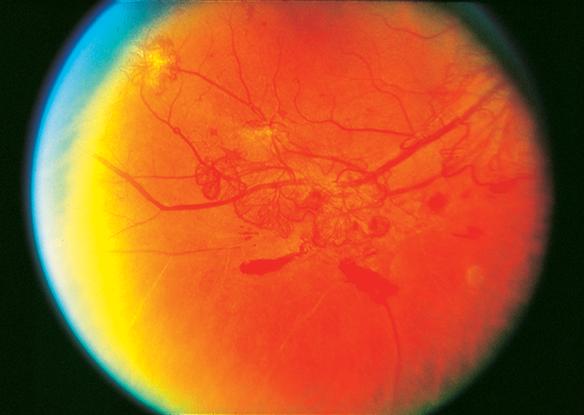

Figure 12. Moderate neovascularization elsewhere with preretinal hemorrhage. (Reproduced, with permission, from Schubert HD. Retina and Vitreous. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 12, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014. Standard photograph 7, courtesy of ETDRS.)

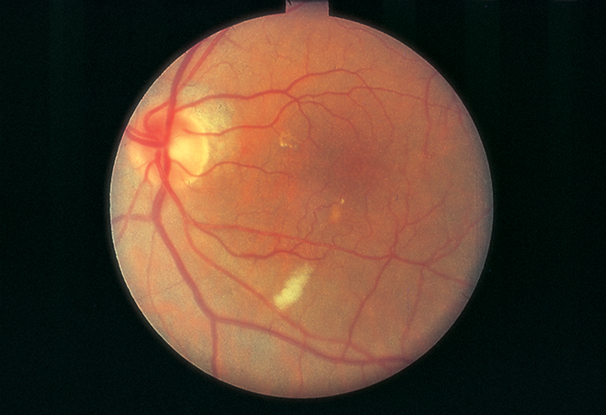

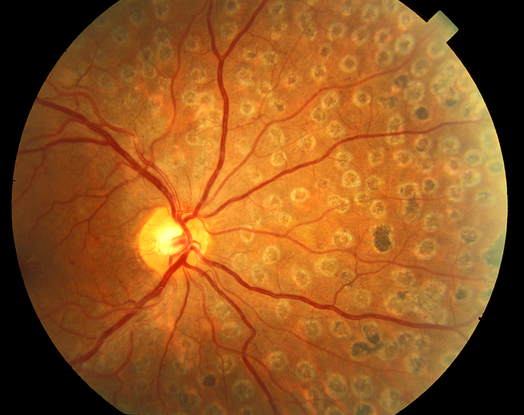

Figure 13. Diffuse intraretinal hemorrhages (arrow) and microaneurysms in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. (Reproduced, with permission, from Schubert HD. Retina and Vitreous. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 12, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014. Courtesy of ETDRS.)

Figure 14. Venous beading in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. (Reproduced, with permission, from Schubert HD. Retina and Vitreous. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 12, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014. Courtesy of ETDRS.)

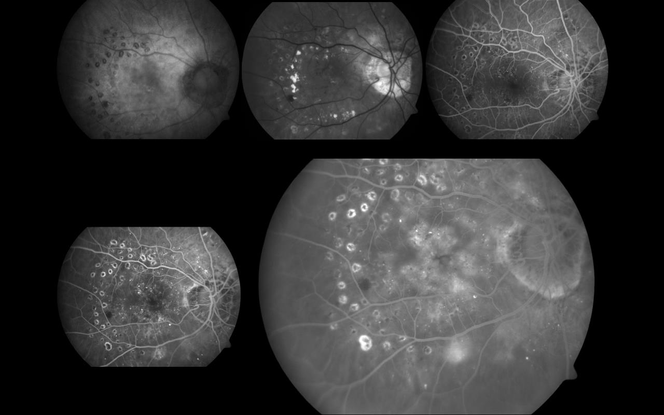

Figure 15. Intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMAs) in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Fluorescein angiogram showing microaneurysms, areas of nonperfusion, and intraretinal capillary remodeling. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

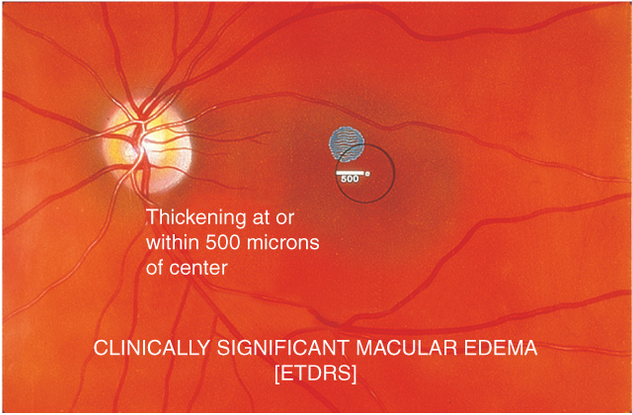

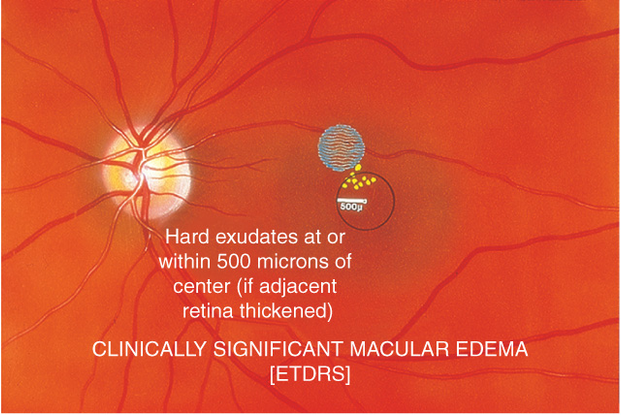

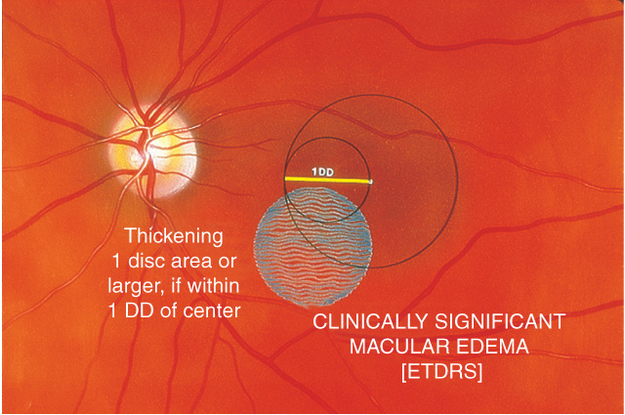

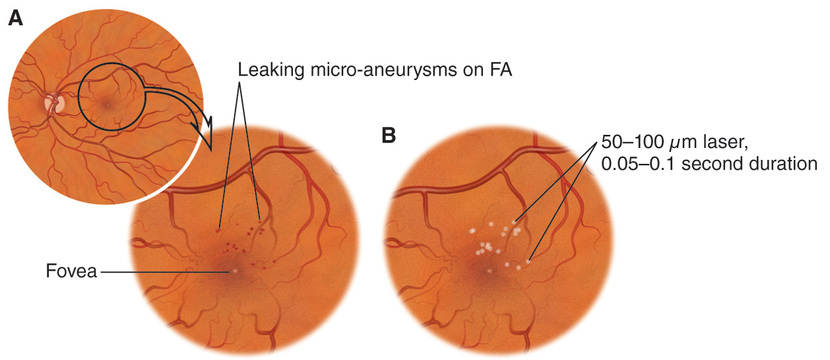

Treatment

Figure 16. Clinically significant macular edema. Retinal edema located at or within 500 μm of center of macula. (Reproduced, with permission, from Schubert HD. Retina and Vitreous. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 12, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014. Courtesy of ETDRS.)

Figure 17. Clinically significant macular edema. Hard exudates ≤500 μm of center of macular if associated with adjacent edema. (Reproduced, with permission, from Schubert HD. Retina and Vitreous. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 12, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014. Courtesy of ETDRS.)

Figure 18. Clinically significant macular edema. A zone of thickening larger than 1 disc area within 1 disc diameter of the center of the macula. (Reproduced, with permission, from Schubert HD. Retina and Vitreous. Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 12, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2013–2014. Courtesy of ETDRS.)

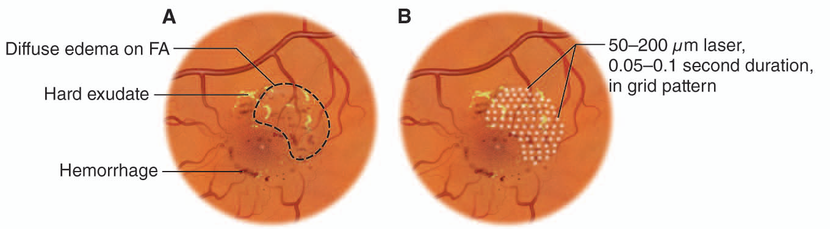

Figure 19. Treatment with focal laser photocoagulation. (Reproduced, with permission, from Dunn JP et al. Basic Techniques of Ophthalmic Surgery, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2009.)

Figure 20. Treat with grid laser photocoagulation for diffuse clinically significant diabetic macular edema. (Reproduced, with permission, from Dunn JP et al. Basic Techniques of Ophthalmic Surgery, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2009.)

Management

Figure 21. Scatter panretinal photocoagulation (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 22. Vitreous hemorrhage w/decreased vision for more than 3 months. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 23. Traction retinal detachment involving the macula. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 24. Macular epiretinal membrane or displacement of macula. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

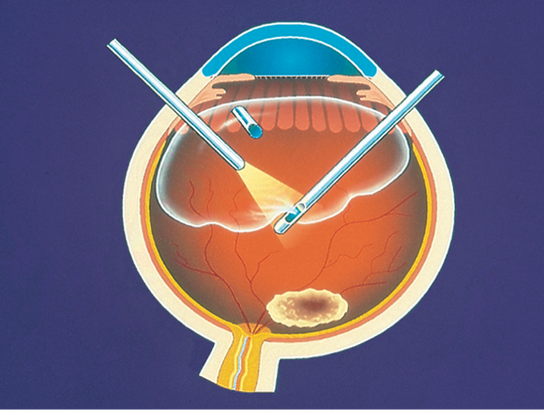

Figure 25. Pars plana vitrectomy. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Case Study

Figure 26. Posterior subcapsular cataract, right eye.

Figure 27. Fundus examination. A. Right eye, very hazy view. B. Left eye, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy.

REFERENCES

American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern®Guidelines. Diabetic Retinopathy. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2008 (4th printing 2012). Available at: https://www.aao.org/ppp.

Al-Adsani. Risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in Kuwaiti type 2 diabetic patients. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:579–583.

Al Alawi E, Ahmed AA. Screening for diabetic retinopathy: the first telemedicine approach in a primary care setting in Bahrain. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:295–298

al-Mahroos F, McKeigue PM. High prevalence of diabetes in Bahrainis. Associations with ethnicity and raised plasma cholesterol. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:936–942.

Al-Maskari F, El-Sadig M. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United Arab Emirates: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Ophthalmology. 2007 June 16;7:11.

Bandello F, Cunha-Vaz J, Chong NV, et al. New approaches for the treatment of diabetic macular edema: recommendations by an expert panel. Eye. 2012;26:485-493.

el Haddad OA, Saad MK. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy among Omani diabetics. Br J Ophthlamol.1998;82:901–906.

Heydari B, Yaghoubi G, Yaghoubi MA, Miri MR. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy: an Iranian eye study. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2012;22:393–397.

Janghorbani M, Amini M, Ghanbar H, Safaiee H. Incidence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in Isfahan, Iran. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2003;10:80–95.

Khan AR, Wiseberg JA, Lateef ZA, Khan SA. Prevalence and determinants of diabetic retinopathy in Al Hasa region of Saudi Arabia: primary health care centre based cross-sectional survey, 2007–2009. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2010;17:257–263.

Khandekar R. Screening and public health strategies for diabetic retinopathy in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:178–184.

Nwosu SN. Diabetic retinopathy in Nnewi, Nigeria. Nig J Ophthamol. 2000;8:7–10.

Nwosu SN. Low vision in Nigerians with diabetes mellitus. Doc Ophthalmol. 2000;101(1):51–57.

Prokofyeva E, Zrenner E. Epidemiology of major eye diseases leading to blindness in Europe: a literature review. Ophthalmic Res. 2012;47:171–188.

Rabiu MM, Kyari F, Ezelum C, et al. Review of the publications of the Nigeria national blindness survey: methodology, prevalence, causes of blindness and visual impairment and outcome of cataract surgery. Ann Afr Med. 2012;11:125–130.

World Health Organization. “Diabetes Fact Sheet.” Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2011.

Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al; Meta-Analysis for Eye Disease (META-EYE) Study Group. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:556–564.

Zhang X, Saaddine JB, Chou CF, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United States, 2005–2008. JAMA. 2010;304:649–656.

CONTRIBUTORS

Executive Editor:

R. V. Paul Chan, MD, FACS, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Section Editor:

Sub-Saharan Africa:

Bolutife Olusanya, MBBS(Ib), MSc, FWACS, FMCOphth

Assistant Editors:

Swetangi D. Bhaleeya, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Kristin Chapman, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Peter Coombs, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Michael Klufas, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Samir Patel, medical student, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Region Contributor:

Tunji S. Oluleye, MD, University of Ibadan and University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria

Copyright © 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology®. All Rights Reserved.