EPIDEMIOLOGY

Global Information

- Worldwide, diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness among working-aged adults.

- The global burden of diabetic retinopathy includes:

- 387 million people with diabetes mellitus (DM) in the world, estimated to increase to 592 million people in 2035.

- 93 million people with diabetic retinopathy

- Affects 1 out of 3 persons with diabetes mellitus

- Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR): 17 million people

- Diabetic macular edema: 21 million people

- Vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy: 28 million people

- Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy is worldwide with only slight ethnic differences.

- Worldwide prevalence of DR in patients with type 1 DM is 77.3% and with type 2 is 25.1%.

- Changes in diet and lifestyle are suspected in the increase in DR prevalence.

- Earlier detection of DR in patients with diabetes, owing to better health care systems, contributes to the prevalence figures.

- 5%-8% of people with DR will need laser treatment.

- 3%-10% will have diabetic macular edema and 30% of them will have visual impairment.

- 0.5% of diabetic patients will need a vitrectomy.

Region-Specific Information (Middle East)

- Six of the 10 countries with the highest prevalence of diabetes in the world are in the Middle East (Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates).

- The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy ranges from 19% in the UAE to 64% in Jordan (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy in the Middle East

|

|

Saudi Arabia

|

19.7%

|

|

Yemen

|

55%

|

|

Qatar

|

23.5%

|

|

Kuwait

|

up to 40%

|

|

Egypt

|

20%

|

|

Jordan

|

up to 64%

|

|

Iraq

|

37%

|

|

UAE

|

19%

|

|

Iran

|

29.6%

|

|

Bahrain

|

25.8%

|

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/DEFINITION

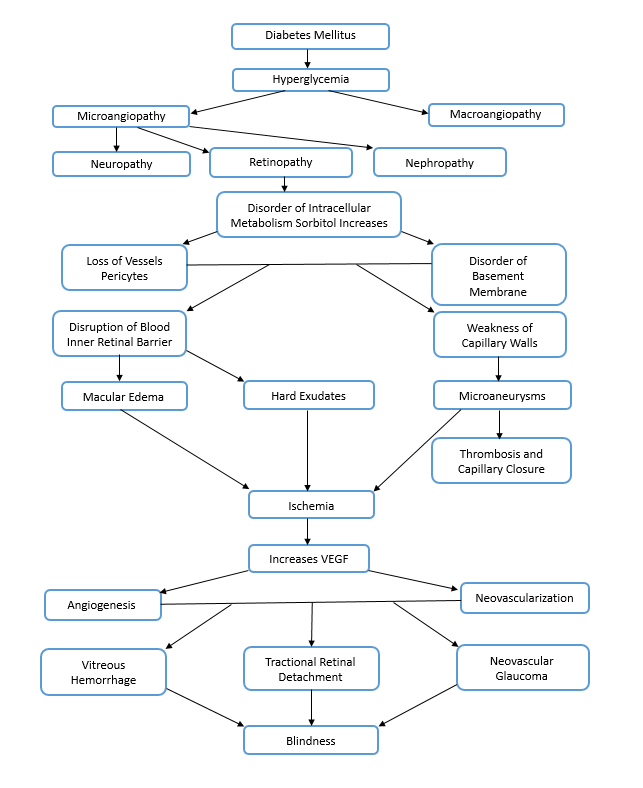

Chart 1. Pathophysiology.

Risk Factors

Duration of Diabetes

Type 1 DM

- 25% of patients will have DR after 5 years, 60% after 10 years and 80% after 15 years

- 50% of patients under 30 years old will develop PDR if duration of DM is 20 years or more (WESDR)

- 18% of patients after 15 years of diagnosis will develop PDR with no difference between type 1 and 2 (LALES-VER)

Type 2 DM

- Patients >30 year 19 years, percentages are 84% and 53% respectively.

- PDR will develop in 2% of patients if duration of DM is < 5 years and 25% if > 25 years

Glycemic control

- Key modifiable risk factor

- Recommendation: Hb A1c 7% or 6.5% in selected cases

High Blood Pressure

- Slows progression of diabetic retinopathy

Blood Lipids

- Slows progression of diabetic retinopathy

Pregnancy

- Gestational diabetes does not require an eye examination during pregnancy and does not increase the risk of diabetic retinopathy.

- Diabetic retinopathy can worsen during pregnancy; patients should have an eye examination before pregnancy and during the first trimester.

- If a patient has no retinopathy or mild to moderate NPDR, examinations should be performed every 3 to 12 months.

- If a pregnant patient has severe NPDR or worse, eye examinations should be performed every 1 to 3 months.

- If neovascularization is detected during pregnancy, laser therapy should be performed.

- Macular edema in pregnant patients can improve with delivery, no intravitreal anti-VEGF is recommended. Consider intravitreal steroids.

- Diabetic retinopathy in a pregnant patient is not a contraindication for natural vaginal delivery.

Renal Impairment

Age

Clotting factors +

Renal Disease +

Physical Inactivity +

Inflammatory Biomarkers +

+ Encourage patients to be compliant with all medical aspects of their disease as these factors are associated with substantial cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

PATIENT HISTORY

- Medical history

- Micro- and macrovascular complications

- Meds: Insulin, oral hypoglycemics

- Duration and type of diabetes

- HbAc1

- Ocular history

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

- Visual acuity

- Intraocular pressure

- Slit lamp biomicroscopy

- Gonioscopy before dilating pupils

- Funduscopic examination of the posterior pole under dilated pupil

- Examination of peripheral retina and vitreous under dilated pupil

- Examination findings consistent with pathophysiology (Chart 1)

SIGNS/SYMPTOMS

- Asymptomatic

- Decreased vision

- Floaters

- Metamorphopsia

- Symptoms of retinal detachment

- Cotton-wool spots (Figure 8)

CLASSIFICATION

Classification of Diabetic Retinopathy

|

Table 2. International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy Disease Severity Scale

|

|

Proposed Disease

Severity Level

|

Findings Observable Upon Dilated Ophthalmoscopy

|

|

No apparent retinopathy

|

No abnormalities

|

|

Mild NPDR

|

Microaneurysms only (Figure 13)

|

|

Moderate NPDR

|

More than just microaneurysms but less severe NPDR

|

|

Severe NPDR

|

US Definition

Any of the following (4-2-1 rule) and no signs of proliferative retinopathy:

- Severe intraretinal hemorrhages and microaneurysms in each of four quadrants

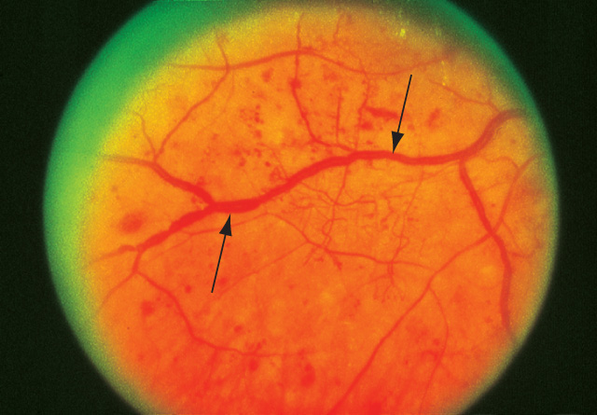

- Definite venous beading in 2 or more quadrants (Figure 14)

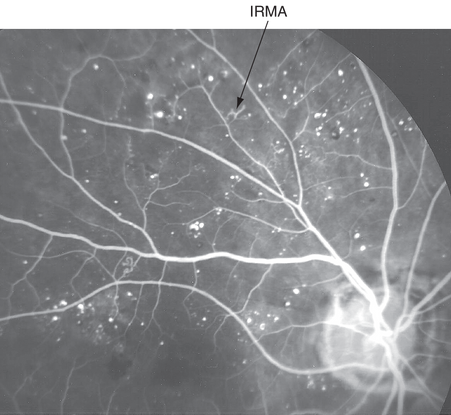

- Prominent IRMA in 1 or more quadrants (Figure 15)

International Classification

Any of the following and no signs of PDR

- More than 20 intraretinal hemorrhages in each of four quadrants

- Definite venous beading in two or more quadrants

- Prominent IRMA in one or more quadrants

|

|

PDR

|

One of both of the following:

|

IRMA = intraretinal microvascular abnormalities; NPDR = nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina-Vitreous Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Diabetic Retinopathy. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2014. Available at: www.aao.org/ppp.

Classification of Diabetic Macular Edema

|

Table 1. International Diabetic Macular Clinical Edema Severity Scale

|

|

Propose Disease Severity Level

|

Findings Observable Upon Dilated Ophthalmoscopy

|

|

Diabetic macular edema apparently absent

|

No apparent retinal thickening or hard exudates in posterior pole

|

|

Diabetic macular edema apparently present

|

Some apparent retinal thickening or hard exudates in posterior pole

|

|

If diabetic macular edema is present, it can be categorized as follows:

|

|

Propose Disease Severity Level

|

Findings Observable Upon Dilated Ophthalmoscopy

|

|

Diabetic macular edema present

|

Mild diabetic macular edema: Some retinal thickening or hard exudates in posterior pole but distant from the center of the macula

|

|

|

Moderate diabetic macular edema: Retinal thickening or hard exudates approaching the center of the macular but not involving the center

|

|

|

Severe diabetic macular edema: Retinal thickening or hard exudates involving the center of the fovea

|

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina -Vitreous Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Diabetic Retinopathy. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2014. Available at: www.aao.org/ppp.

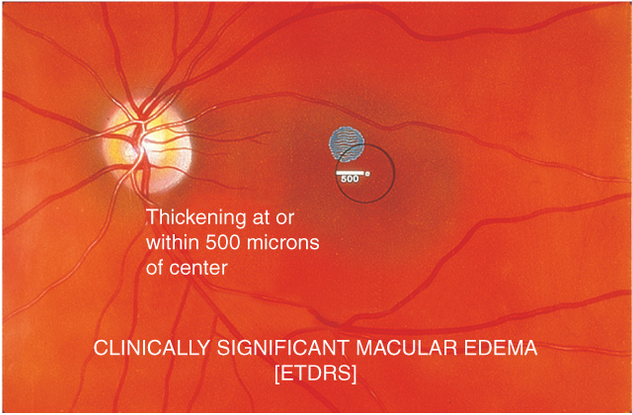

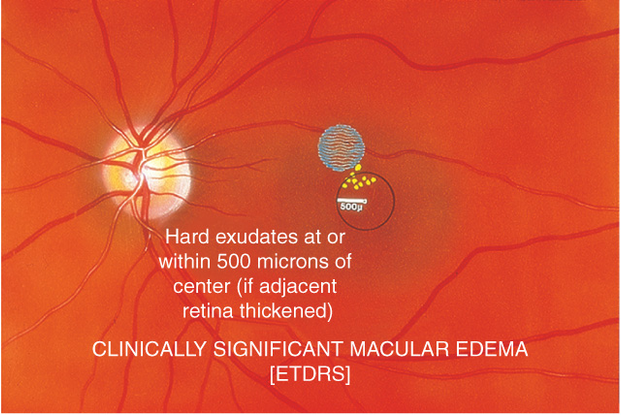

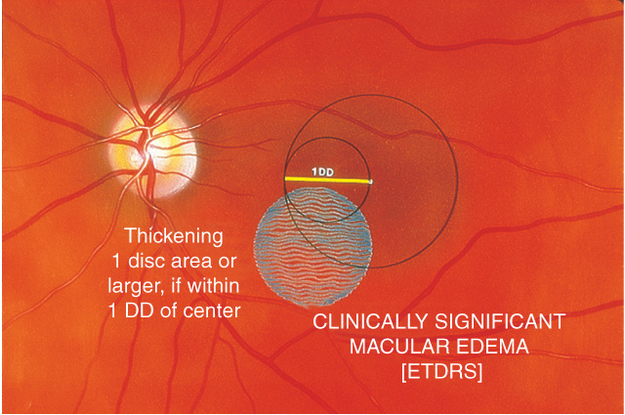

Clinically Significant Macular Edema

|

Table 2. Clinically Significant Macular Edema

|

- Retinal edema located at or within 500 μm of the center of the macula

- Hard exudates at or within 500 μm of the center if associated with thickening of adjacent retina

- A zone of thickening larger than 1 disc area if located within 1 disc diameter of the center of the macula

|

Source: Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 12, American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2014-2015.

TREATMENT OF DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

- Treatment strategies are effective in 90% of cases to prevent severe visual loss.

- Most important factor in medical management of diabetic retinopathy is good glycemic control, which is associated with reduced risk of newly diagnosed retinopathy and of progression of existing retinopathy. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial-United Kingdom Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DCCT-UKPDS).

- Adequate control of hypertension reduces progression of retinopathy and loss of vision (UKPDS)

- Encourage changes in lifestyles and good metabolic control in all diabetic patients

- Treatment options

- Laser therapy

- Anti-VEGF drugs (bevacizumab, ranibizumab, aflibercept)

- Surgery

TREATMENT OF DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA

Available therapies are:

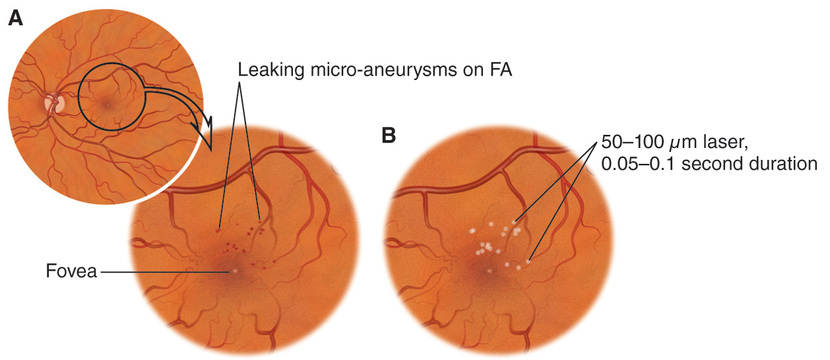

Laser Therapy

- Focal laser : FDA approved based on ETDRS findings

- Micropulse laser

Anti-VEGF Drugs

- Aflibercept : 2mg every 8 weeks after 5 initial monthly injections: Approved by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in July 2014 based on VIVID-VISTA clinical trials results

- Ranibizumab: 0.3 mg monthly Approved by FDA in August 2012 based on RISE- RIDE clinical trials results

- Bevacizumab: Off-label use worldwide

Steroids

- Intravitreal Injections

- Intravitreal implants

- Ozurdex (Dexamethasone): 0.7 mg, re-treatment after 6 months of previous treatment. Approved by FDA in June 2014 based on the MEAD study.

- Iluvien (Flucinolone Acetonide): 0.19 mg last up to 36 months Approved by FDA in September 2014 based on the FAME study.

Anti-VEGF Drugs

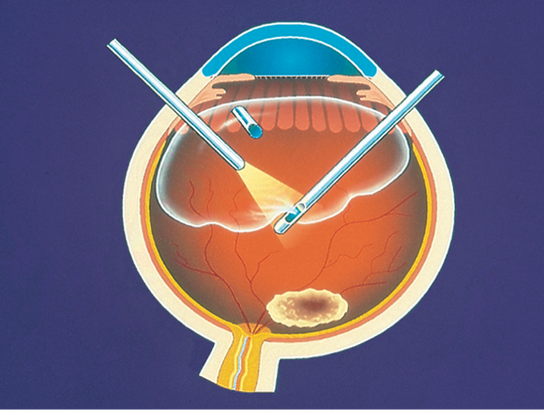

Surgery

- Consider in cases of vitreomacular traction

|

Table 1. Management Recommendations for Patients With Diabetes

|

|

Severity of Retinopathy

|

Presence of Macular Edema

|

Follow-Up Months

|

Panretinal Photocoagulation

(Scatter) Laser

|

Focal and/or Grid Laser *

|

Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Therapy

|

|

Normal or minimal NPDR

|

No

|

12

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

| Mild NPDR |

No |

12 |

No |

No |

No |

|---|

| ME |

4-6 |

No |

No |

No |

| CSME |

1 |

No |

Sometimes |

Sometimes |

| Moderate NPDR |

No |

6-12 |

No |

No |

No |

|---|

| ME |

3-6 |

No |

No |

No |

| CSME |

1 |

No |

Sometimes |

Sometimes |

| Severe NPDR |

No |

4 |

Sometimes |

No |

No |

|---|

| ME |

2- 4 |

Sometimes |

No |

No |

| CSME |

1 |

Sometimes |

Sometimes |

Sometimes |

| Non-High-Risk NPDR |

No |

4 |

Sometimes |

No |

No |

|---|

| ME |

4 |

Sometimes |

No |

No |

| CSME |

1 |

Sometimes |

Sometimes |

Sometimes |

| High-Risk NPDR |

No |

4 |

Recommended |

No |

Consider |

|---|

| ME |

4 |

Recommended |

Sometimes |

Usually |

| CSME |

1 |

Recommended |

Sometimes |

Usually |

CSME: clinically significant macular edema. ME: Non-clinically significant macular edema. NPDR: Nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. PDR: Proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Anti VEGF: anti-vascular endothelial growth factor

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina -Vitreous Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Diabetic Retinopathy. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2014. Available at: www.aao.org/ppp.

CASE STUDY

History of Present Illness

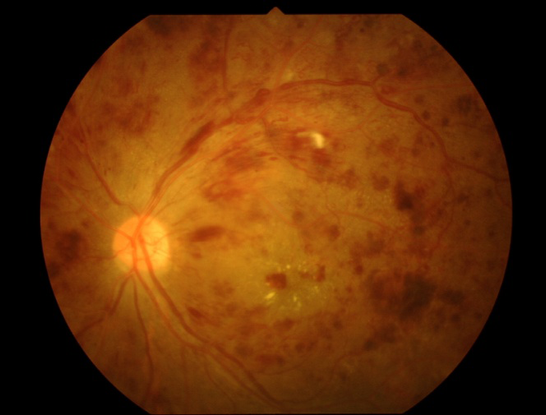

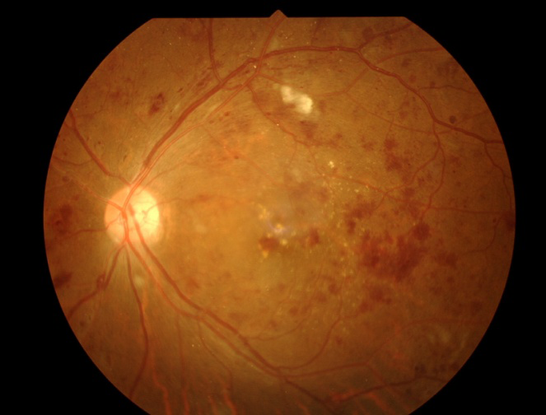

A 68-year-old male patient complained of poor vision in his left eye. He had never had an eye examination before and was not aware of the recommendation for an annual eye exam.

Past Medical History

Diabetes mellitus type 2 diagnosed 1 year ago. He reported that his blood sugar was well controlled. His HbA1c was 5.9%.

Examination

- Visual acuity: 20/30 right eye, 20/60 left eye

- Extraocular movements: Full

- Intraocular pressure: 16 mm Hg OU

- Cornea: clear both eyes

- Anterior chamber: deep and quiet, with no neovascularization of the iris

- Lens: Nuclear sclerotic cataract both eyes (+)

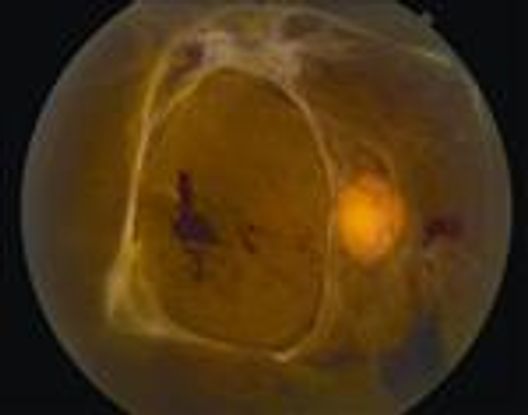

- OD: moderate NPDR and no macular edema. (Figure 27A).

- OS: moderate NPDR with severe macular edema. (Figure 27B)

Treatment

- Recommended that the patient undergo anti-VEGF treatment in his left eye.

- The patient underwent 4 injections of aflibercept in the left eye monthly, followed up with OCT on each visit. Visual acuity improved to 20/20.

IMAGE LIBRARY

Differential Diagnosis

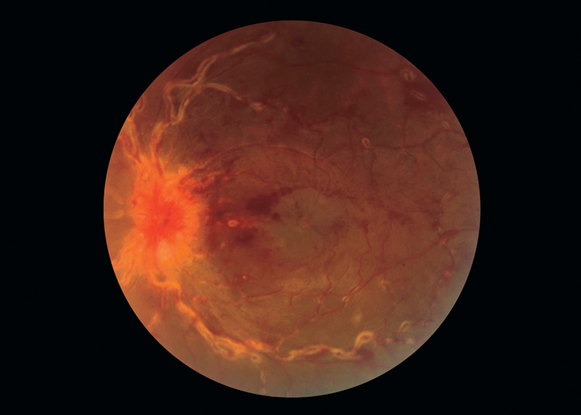

Figure 1. Hypertensive retinopathy. Note the disc edema, macular exudates, intraretinal hemorrhage with nerve fiber layer infarct, and venous congestion.

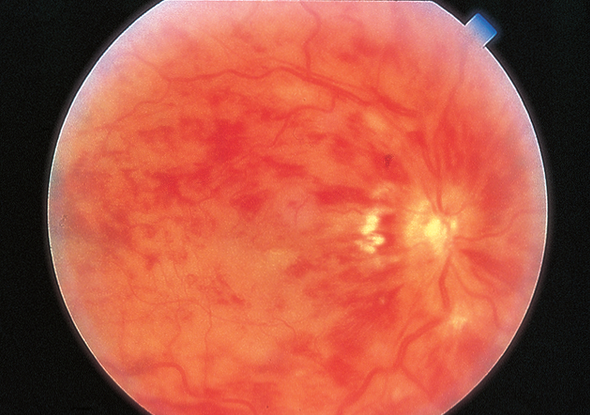

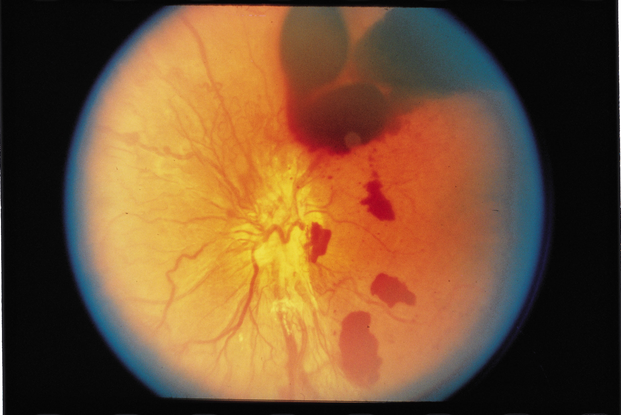

Figure 2. Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). CRVO in an eye with hand motions vision. The veins are dilated, and retinal hemorrhages are present.

Figure 3. Branch retinal vein occlusion.

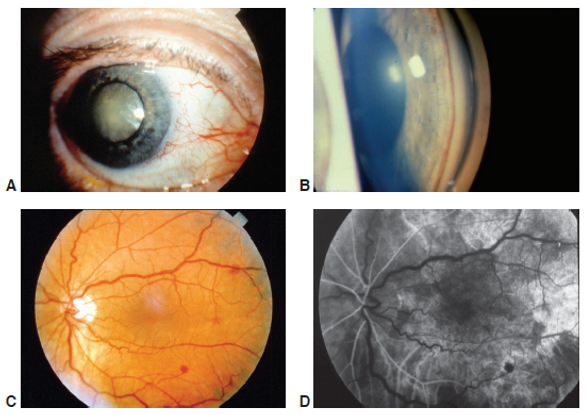

Figure 4. Ocular ischemic syndrome. A, Clinical photograph of an eye with ocular ischemic syndrome displaying features of conjunctival injection, cataract, and rubeosis irides. B, Gonioscopic appearance of neovascularization of the iridocorneal angle due to ocular ischemic syndrome. C, Fundus photograph of an eye with ocular ischemic syndrome showing features of venous dilation, midperipheral intraretinal hemorrhages, and attenuated arterioles. D, Fluorescein angiography image at 19 seconds (arterial phase) demonstrating a prolonged arm-to-retina circulation time and a patchy choroidal filling pattern.

Figure 5. Radiation retinopathy. Image of an eye that has undergone plaque brachytherapy for treatment of choroidal melanoma. The melanoma can be seen nasally, obscuring part of the disc.

Figure 6. Sickle cell retinopathy, with peripheral neovascularization (“sea fan” neovascularization) with autoinfarction.

Figure 7. Sarcoidosis, with retinal vascular sheathing.

Pathophysiology/Definition

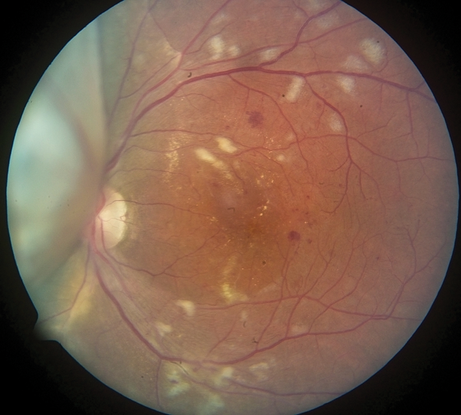

Figure 8. Cotton-wool spot (capillary retinal arteriole obstruction).

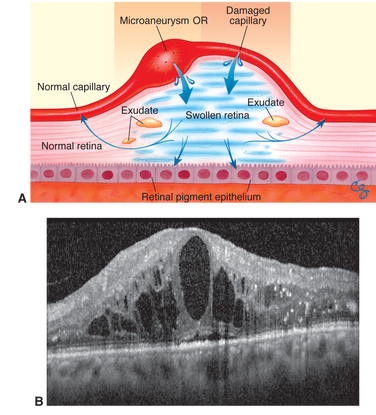

Figure 9. Diabetic macular edema. A.Mechanism of diabetic macular edema, demonstrating development of thickening from a breakdown of the blood–retinal barrier. B. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomogram of diabetic macular edema. Note the foveal detachment.

Figure 10. Retinal neovascularization. (Image courtesy of Kellogg Eye Center, University of Michigan.)

Figure 11. Tractional retinal detachment. There is associated hemorrhage due to traction on fronds of neovascular ingrowth.

Management Classification

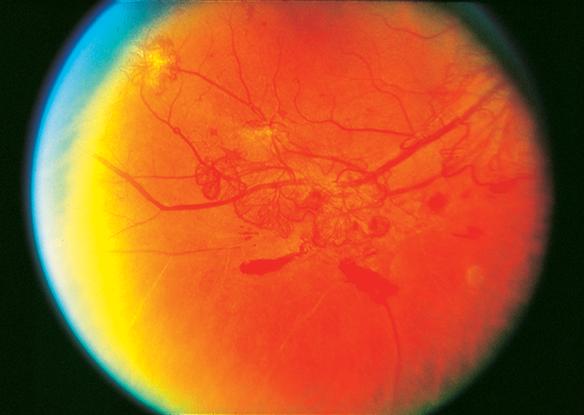

Figure 12. Moderate neovascularization elsewhere with preretinal hemorrhage. (Reproduced, with permission, from Schubert HD.

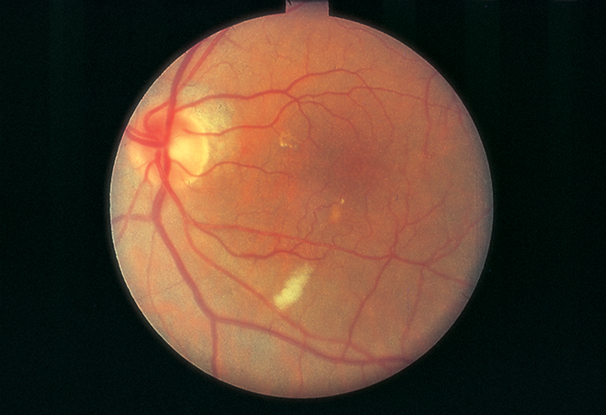

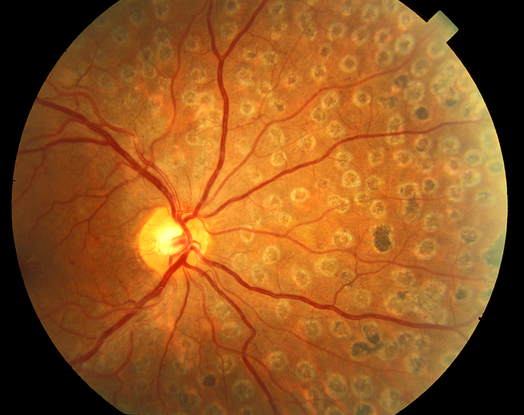

Figure 13. Diffuse intraretinal hemorrhages (arrow) and microaneurysms in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Figure 14. Venous beading in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Figure 15. Intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMAs) in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Fluorescein angiogram showing microaneurysms, areas of nonperfusion, and intraretinal capillary remodeling.

Treatment

Figure 16. Clinically significant macular edema. Retinal edema located at or within 500 μm of center of macula.

Figure 17. Clinically significant macular edema. Hard exudates ≤500 μm of center of macular if associated with adjacent edema.

Figure 18. Clinically significant macular edema. A zone of thickening larger than 1 disc area within 1 disc diameter of the center of the macula.

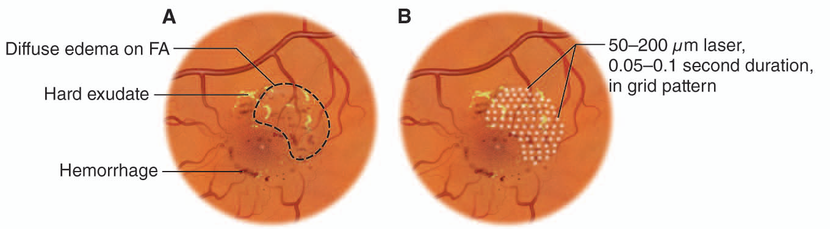

Figure 19. Treatment with focal laser photocoagulation.

Figure 20. Treat with grid laser photocoagulation for diffuse clinically significant diabetic macular edema.

Management

Figure 21. Scatter panretinal photocoagulation

Figure 22. Vitreous hemorrhage w/decreased vision for more than 3 months.

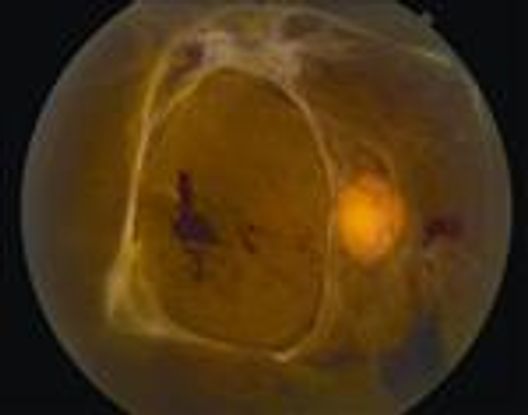

Figure 23. Traction retinal detachment involving the macula.

Figure 24. Macular epiretinal membrane or displacement of macula.

Figure 25. Pars plana vitrectomy.

Figure 26. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy. (Top) Before treatment. (Bottom). One week after intravitreal injection with bevacizumab, the patient’s fundus examination showed much improvement.

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Ophthalmology Retina -Vitreous Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Diabetic Retinopathy. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2014. Available at: www.aao.org/ppp.

- Martinez J, Hernandez-Bogantes E, Wu L. Diabetic retinopathy screening using single-field digital fundus photography at a district level in Costa Rica: a pilot study. Int Ophthalmol. 2011;31:83–88.

- Lee R, Wong Tien Y Sabanayagam C. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema and related vision loss. Eye Vis (Lond). 2015;2:17.

- Raum P, Lamparter J, Ponto KA, et al. Prevalence and Cardiovascular Associations of Diabetic Retinopathy and Maculopathy: Results from the Gutenberg Health Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0127188.

- Blum M, Kloos C, Müller N, et al. [Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy. Check-up program of a public health insurance company in Germany 2002-2004]. Ophthalmologe. 2007;104(6):499-500, 502-504.

- Guía Clinica de Retinopatía Diabética para Latinoamérica 2015. Panamerican Association of Ophthalmology- International Counseling of Ophthalmology- Programa vision 2020 IAPB LatinAmerica.

- Bandello F, Cunha-Vaz J, Chong NV, et al. New approaches for the treatment of diabetic macular oedema: recommendations by an expert panel. Eye. 2012;26:485-493.

- Al-Adsani AM. Risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in Kuwaiti type 2 diabetic patients. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:579–583.

- Al Alawi E, Ahmed AA. Screening for diabetic retinopathy: the first telemedicine approach in a primary care setting in Bahrain. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:295–298.

- al-Mahroos F, McKeigue PM. High prevalence of diabetes in Bahrainis. Associations with ethnicity and raised plasma cholesterol. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:936–942.

- Al-Maskari F, El-Sadig M. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United Arab Emirates: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Ophthalmology. 2007;7:11.

- el Haddad OA, Saad MK. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy among Omani diabetics. Br J Ophthlamol. 1998;82:901–906.

- Heydari B, Yaghoubi G, Yaghoubi MA, Miri MR. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy: an Iranian eye study. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2012;22:393–397.

- Janghorbani M, Amini M, Ghanbar H, Safaiee H. Incidence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in Isfahan, Iran. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2003;10:80–95.

- Khan AR, Wiseberg JA, Lateef ZA, Khan SA. Prevalence and determinants of diabetic retinopathy in Al Hasa region of Saudi Arabia: primary health care centre based cross-sectional survey, 2007–2009. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2010;17:257–263.

- Khandekar R. Screening and public health strategies for diabetic retinopathy in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:178–184.

- Nwosu SN. Diabetic retinopathy in Nnewi, Nigeria. Nig J Ophthamol. 2000;8:7–10.

- Nwosu SN. Low vision in Nigerians with diabetes mellitus. Doc Ophthalmol. 2000;101(1):51–57.

- Prokofyeva E, Zrenner E. Epidemiology of major eye diseases leading to blindness in Europe: a literature review. Ophthalmic Res. 2012;47:171–188.

- Rabiu MM, Kyari F, Ezelum C, et al. Review of the publications of the Nigeria national blindness survey: methodology, prevalence, causes of blindness and visual impairment and outcome of cataract surgery. Ann Afr Med. 2012; 11:125–130.

- World Health Organization. “Diabetes Fact Sheet.” Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2011.

- Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al; Meta-Analysis for Eye Disease (META-EYE) Study Group. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:556–564.

- Zhang X, Saaddine JB, Chou CF, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United States, 2005–2008. JAMA. 2010; 304:649–656.

CONTRIBUTORS

Executive Editor:

R. V. Paul Chan, MD, FACS, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Section Editor:

North Africa/Middle East:

Ebtisam S. Kadhem Al-Alawi, FRCS, MRCOpht, DO, Salmaniya Medical Center, Bahrain

Assistant Editors:

Swetangi D. Bhaleeya, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Kristin Chapman, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Peter Coombs, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Michael Klufas, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Samir Patel, medical student, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Region Contributor:

Mariam A. Hadi Almohsen, Senior Resident, Salmaniya Medical Complex, Bahrain

Copyright © 2016 American Academy of Ophthalmology®. All Rights Reserved.