EPIDEMIOLOGY

Global Information

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a DNA virus.

- 80% of the world’s population has been exposed to HSV type 1 (HSV-1).

- Transmission is through close personal contact.

- Refer to Table 1 for global data related to herpes simplex keratitis (HSK).

|

Table 1. Keratitis Incidence, Rate and Incidence of Severe Visual Impairment.

|

|

Category

|

Keratitis Incidence (per year)

|

Rate of Severe Visual Impairment

|

Incidence of Severe Visual Impairment (per year)

|

|

Developed nations1

|

241,597

|

0.015

|

3,624

|

|

Developing nations

|

1–1.5 million

|

0.03

|

30,000–45,000

|

|

Total

|

~1.5 million

|

n/a

|

~40,0000

|

|

1Developed nations were categorized as having “very high human development” by the United Nations Development Program. This list includes Norway, Australia, New Zealand, USA, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Netherlands, Canada, Sweden, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, France, Israel, Finland, Iceland, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, Hong Kong, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Austria, UK, Singapore, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Andorra, Slovakia, U.A.E., Malta, Estonia, Cyprus, Hungary, Brunei, Qatar, Bahrain, Portugal, Poland, and Barbados.

|

Regional Information (Africa/Middle East)

Table 2. Seroprevalence Estimate for HSV-1 and HSV-2 for the African and Middle Eastern Regions |

|

Country

|

Prevalence (%)

|

|

HSV-1

|

HSV-2

|

|

Total

|

Female

|

Male

|

|

Cameroon

|

–

|

46–51

|

24–27

|

|

Central African Republic

|

99

|

82

|

–

|

|

Kenya

|

–

|

68

|

35

|

|

Mali

|

93

|

43

|

–

|

|

Morocco

|

99

|

26

|

–

|

|

South Africa

|

–

|

53

|

17

|

|

Uganda

|

91

|

71

|

36

|

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

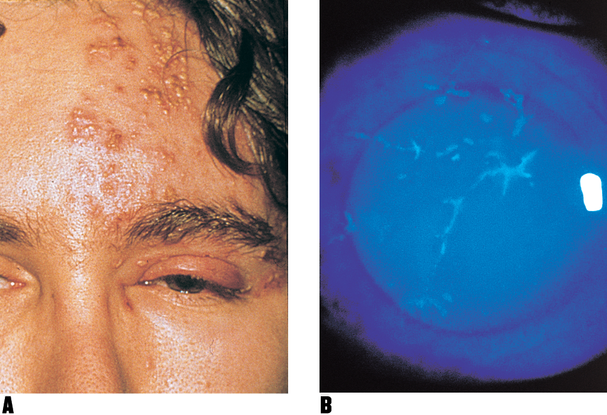

- Varicella zoster virus (Figure 1)

- Recurrent corneal erosion

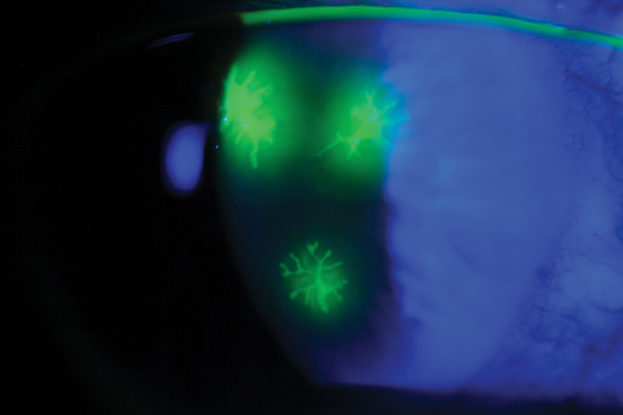

- Acanthamoeba keratitis pseudodendrites (Figure 2)

- Vaccinia keratitis

- Thygeson superficial punctate keratopathy (Figure 3)

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/DEFINITION

- The herpes viruses are classified into 3 families: α, β, and γ.

- HSV-1 is the first member of the human herpes viruses belonging to the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae.

- Herpes simplex keratitis is caused by HSV-1 infection of the corneal epithelium and stroma.

- Epithelial keratitis accounts for 70% to 80% of all cases.

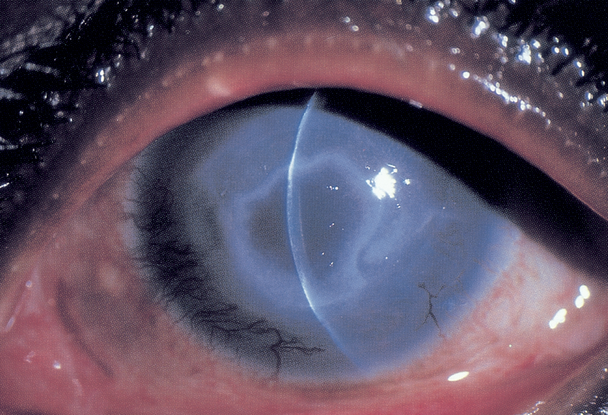

- Dendritic epithelial keratitis, a branching pattern of epithelial infection and erosion, is the typical configuration of HSV epithelial keratitis (Figure 4).

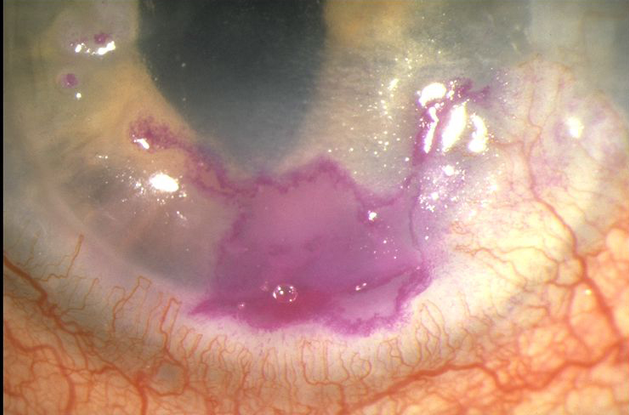

- Geographic epithelial keratitis is a less common, macro-ulcerative form of HSV corneal epithelial infection (Figure 5).

- HSV stromal keratitis accounts for 2% of initial HSV-1 ocular presentations but it is the cause of 20%–61% of recurrent disease.

- After the primary infection, HSV typically becomes quiescent or latent in the trigeminal ganglion.

- Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infection and inflammation may eventually cause corneal scarring, thinning, neovascularization, and stromal keratitis.

Risk Factors for Primary HSV Infection

- Close personal contact with infected person

- Sharing utensils, toothbrushes, and so on with infected person

Associated Risk Factors for Recurrent HSV Infection, Previous Stromal Keratitis

- Fever

- Trauma

- Ultraviolet light

- Stress

- Immune suppression

- Hormonal changes

SIGNS/SYMPTOMS

Signs and symptoms are usually unilateral:

- Red eye

- Pain

- Photophobia

- Tearing

- Decreased vision

- Previous episodes

- Foreign body sensation

Exam Findings

Epithelial disease:

Stromal disease:

- Stromal opacity

- Stromal edema with intact epithelium

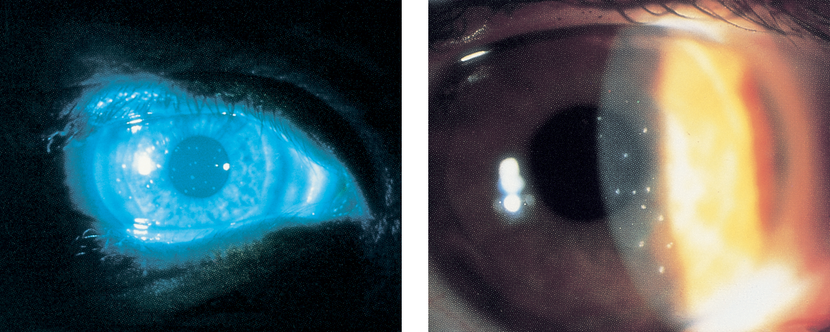

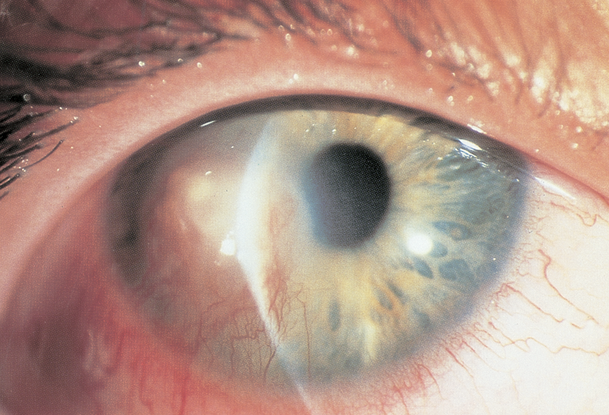

- Vascularization, stromal inflammation (Figure 6)

- Ulceration and thinning

- Endotheliitis

- Disc-shaped or sectorial stromal edema with keratic precipitates in the underling endothelium (Figure 7).

- Associated local scleritis

MANAGEMENT

Epithelial Keratitis

- Treatment shortens the clinical course; it may reduce herpetic neuropathy.

- Depending on geographic location: Prescribe topical trifluridine 1% drops 8 times a day for up to 10 to 14 days.

- Or: Prescribe acyclovir ointment 5 times a day for 10 to 14 days.

- Acyclovir 400 mg PO 5 times a day or valacyclovir 500 mg 3 times a day PO.

- Topical steroids are contraindicated with active epithelial disease.

- Ganciclovir ophthalmic gel, 0.15% (GCV 15%) is available in the United States.

Note: Acyclovir 3% is not available in the United States.

Stromal Keratitis

- Prescribe prednisolone 1% drops 3–6 dd WITH topical trifluridine 4 times a day OR acyclovir 400 mg PO twice a day OR valacyclovir 500 mg PO 2–3 dd.

- If therapy is continued for more than a few weeks, topical antiviral therapy is stopped, continuing oral antiviral therapy to avoid corneal toxicity.

- The Herpetic Eye Diseases Study demonstrated that topical corticosteroids given together with a prophylactic antiviral shorten the duration of herpes simplex stromal keratitis, and found that long-term suppressive oral acyclovir therapy reduces the rate of recurrent HSV keratitis.

- Preventive treatment: acyclovir 400 mg PO 2 dd OR valacyclovir 500 mg PO 1–2 dd, fluorometholone 0.1% 1 dd

Necrotizing Keratitis/Geographic Ulcer

- Prescribe prednisolone 1% drops every 2 hours.

- Prescribe agluecyclovir 400 mg PO 5 dd OR valacyclovir 500 mg PO 3 dd.

Surgical Therapy

- Surgical treatment is indicated when severe stromal keratitis leads to stromal perforation or visually significant stromal scarring.

- Surgical treatment of perforation may include application of cyanoacrylate glue or penetrating keratoplasty (PK).

- Penetrating keratoplasty is the treatment when vision is reduced due to stromal scar after HSV keratitis.

- Success of a PK is 60%–80% if there have been no signs of active disease at least 6 months prior to surgery.

- Graft failure may develop in actively inflamed eyes undergoing PK or in recipient corneas with vascularization in >2 quadrants.

CASE STUDY

A 36-year-old female with past history of eye redness 1 year ago and atopy presents with unilateral (right) eye redness for the past 2 weeks. She has no history of contact lens wear. One week ago, she saw her primary medical doctor, who prescribed a topical antibiotic drop (polymyxin/trimethoprim), which she has been using 4 times a day without relief. Patient denies any eye trauma to that eye.

Slit Lamp Examination

- Unilateral dendritis keratitis without membranes or pseudomembranes.

- Negative for stromal inflammation or anterior chamber or posterior segment inflammation.

Diagnosis

- Differential diagnosis includes HSV keratitis, adenoviral keratitis, Thygeson’s superficial punctuate keratitis, and healing epithelial defect.

- The lack of stromal inflammation or anterior chamber or posterior segment inflammation yields a presumptive diagnosis of HSV epithelial keratitis.

Treatment

- The patient was started on trifluridine 1% drops 8 times a day for 14 days with resolution of symptoms.

- Given the patient had a history of prior eye redness, there was concern for recurrent HSV keratitis in the future, and she was placed on oral antiretroviral prophylaxis (acyclovir 400 mg PO 2 times a day or valacyclovir 500 mg 1 time a day PO) to reduce recurrences in the future.

IMAGE LIBRARY

Differential Diagnosis

Figure 1. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. A. Skin eruptions near the eye and swollen lids. B. Disease cornea stained with diagnostic fluorescein shows the characteristic branch-like (dendritic) pattern of herpetic keratitis. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology. )

Figure 2. Ring infiltrate in Acanthamoeba keratitis. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology,)

Figure 3. Thygeson superficial punctate keratitis. A. Shown with fluorescein staining. B. At higher magnification, each lesion is seen to consist of several minute dots. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Pathophysiology/Definition

Figure 4. Herpes simplex keratitis. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 5. Herpes simplex virus geographic epithelial keratitis. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Signs/Symptoms

Figure 6. Herpetic stromal keratitis. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 7. Herpes simplex virus disciform keratitis. (© 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology.)

File Name: her_s_ke7

REFERENCES

External Disease and Cornea.Section 8, Basic and Clinical Science Course. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2012–2013; 105–119.

Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:448–462.

Friedberg M, Rapuano C. Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room diagnosis and treatment of Eye Disease. 5th ed. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008.

“Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) 1.” www.nei.nih.gov/neitrials/static/study37.asp. Accessed September 18, 2013.

“Herpetic Eye Disease Study (HEDS) 2.” www.nei.nih.gov/neitrials/static/study38.asp. Accessed September 18, 2013.

Kertes P. Evidence Based Eye Care. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007.

Labetoulle M, Auquier P, Conrad H, et al. Incidence of herpes simplex virus keratitis in France. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:888–895.

Papadogeorgakis H, Caroni C, Katsambas A. Herpes simplex virus seroprevalence among children, adolescents and adults in Greece. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:272–278.

Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:S3–28.

Galvis V, Tello A, Revelo ML, Carreño NI. Herpes simplex virus keratitis: epidemiological observations. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58:286–287.

CONTRIBUTORS

Executive Editor: R. V. Paul Chan, MD, FACS, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Section Editors:

North Africa/Middle East:

Ebtisam S. Kadhem Al-Alawi, FRCS, MRCOpht, DO, Salmaniya Medical Center, Bahrain

Assistant Editors:

Swetangi D. Bhaleeya, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Kristin Chapman, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Peter Coombs, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Michael Klufas, MD, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York

Samir Patel, medical student, Weill Cornell Medical College; New York, New York

Regional Contributor:

Hassan Ebrahim, MD, Senior Resident, Salmaniya Medical Complex, Bahrain

Copyright © 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology®. All Rights Reserved.