EPIDEMIOLOGY

Global Information

- Keratoconus affects a preponderance of Indians, Pakistanis, Arabs, and Polynesians compared with Caucasian populations (Kok, 2012).

- Population studies have repeatedly found that Indians and Pakistanis make up a significantly greater percentage of patients with keratoconus, suggesting a genetic component to the disease (Cozma et al, 2005; Davanger, 1978; Georgiou et al, 2004; Pearson et al, 2000).

- The estimated incidence among Caucasians is 50/100,000 (Rabinowitz, 1998).

Regional Information (EUROPE)

- In the United Kingdom, incidence of keratoconus in the Asian populations is at least 9× higher in the Caucasian population.

- See Table 1.

| Table 1. Epidemiological Profile of Keratoconus in Europe |

| Study |

Country |

Prevalence /100,00 |

Incidence /100,000 |

Age of Presentation (years) |

| Georgiou et al, 2004 |

United Kingdom |

- |

Asian: 25

Caucasian: 3.3 |

Asian: 21.5

Caucasian: 26.4 |

| Cozma et al, 2005 |

United Kingdom |

- |

Asian: 32.3

Caucasian: 3.5 |

Asian: 23.0

Caucasian: 27.8 |

| Pearson et al, 2000 |

United Kingdom |

Asian: 229

Caucasian: 57 |

Asian: 19.6

Caucasian: 4.5 |

Asian: 22.3

Caucasian: 26.5 |

| Nielsen et al., 2007 |

Denmark |

86 |

1.3 |

- |

| Ihalainen, 1986 |

Finland |

30 |

1.5 |

24 |

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

- Pellucid marginal degeneration (Figure 1)

- Keratoglobus

- Postrefractive surgery ectasia

- Astigmatism

- Corneal scarring

- Terrien marginal degeneration

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/DEFINITION

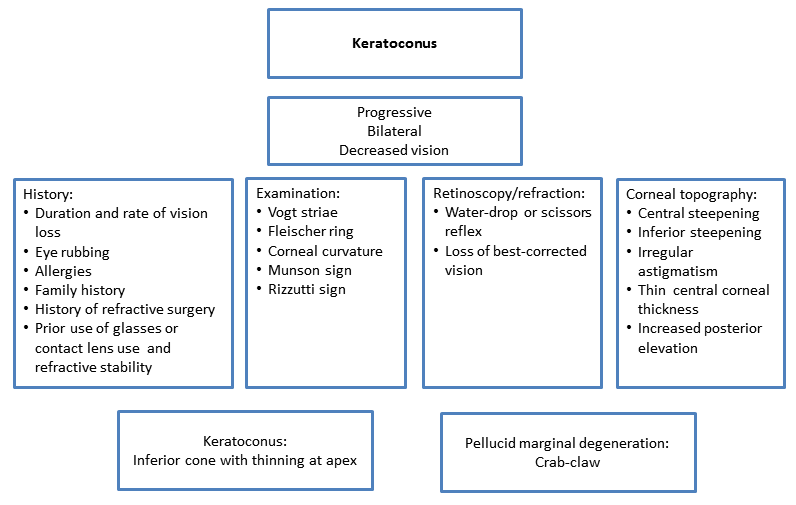

Chart 1. Pathophysiology.

Background

- Keratoconus most commonly presents as a sporadic disorder, but a minority of patients exhibit a family history of an autosomal dominant inheritance.

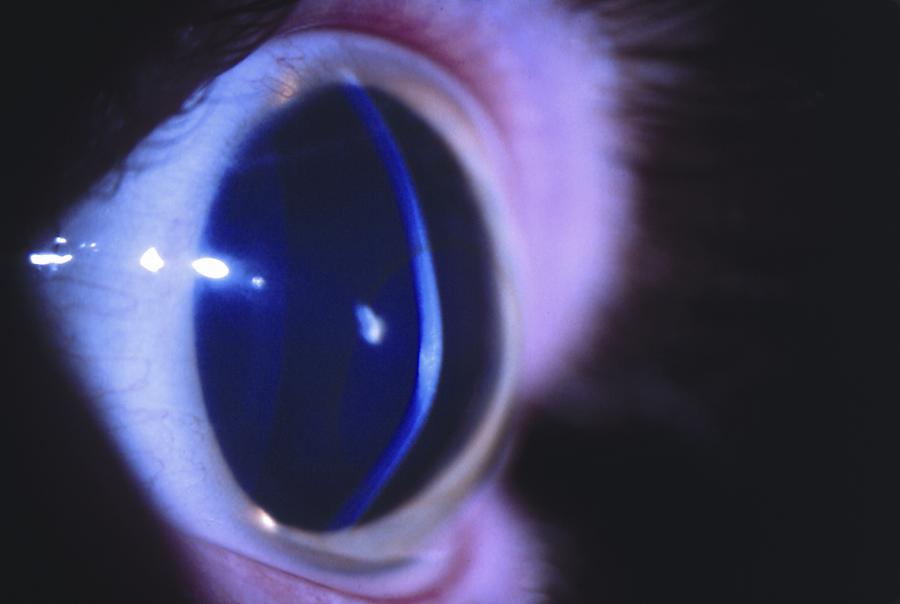

- The condition is often bilateral, often asymmetric, with progressive corneal steepening (Figure 2).

- It is usually diagnosed in the second decade of life.

Suspected Mechanism

- Thinning of the central corneal stroma reduces the number of collagen crosslinks.

- Thinning results in a stiffness that is only 60% of normal cornea tissue and causes the normally dome-shaped cornea to assume a conical shape.

- Deformation creates irregular astigmatism and myopia leading to marked impairment of vision.

Suspected Pathogenesis

- The exact pathogenesis of keratoconus is not fully understood.

- Increased polymorphisms in the interleukin 1 beta (IL-1B) promoter region in an unrelated Korean population suggests that there may be an inflammatory reaction involved in the progression of the disease (Kim et al, 2008).

- It is possible that keratoconus is a spectrum rather than a single entity and is the culmination of several pathological processes.

Associations/Risk Factors

- Down syndrome (in western countries, Cullen et al, 1963)

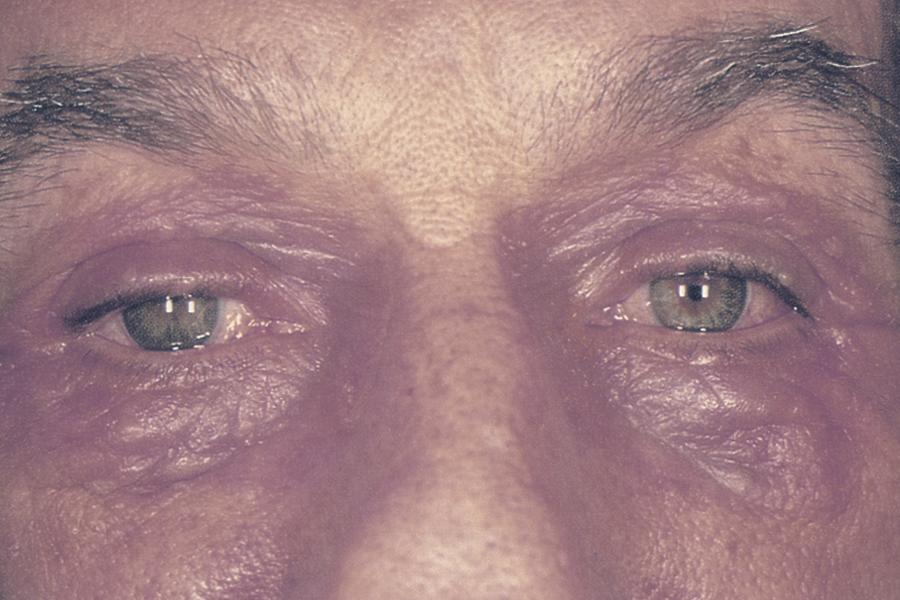

- Atopic disease (Figure 3)

- Turner syndrome

- Leber congenital amaurosis (in India, McKibbin et al, 2010; in Pakistan, Sundaresan et al, 2009)

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Retinitis pigmentosa

- Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos, osteogenesis imperfecta

- Chronic eye rubbing (vernal keratoconjunctivitis)

- Family history 6%–23.5%

SIGNS/SYMPTOMS

Signs

- Best spectacle-corrected visual acuity with normal retina is less than 20/20

- Progressive irregular astigmatism

- Paracentral thinning and bulging of cornea with maximum thinning at apex of protrusion

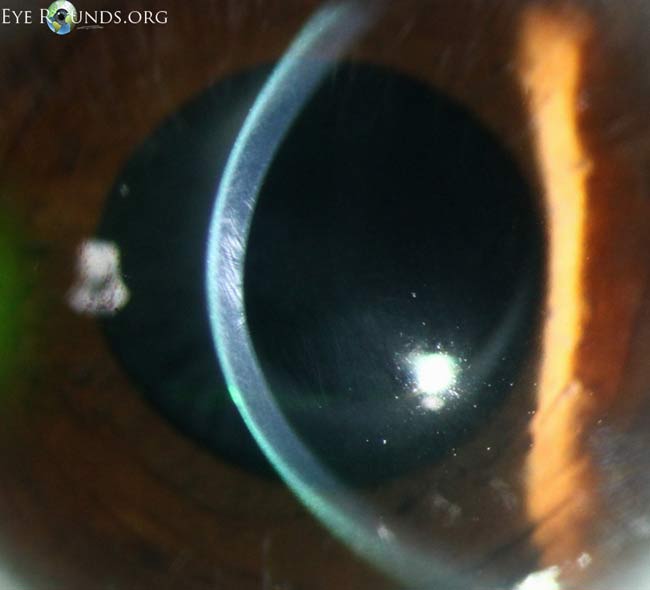

- Vogt striae: vertical tension lines in posterior cornea (Figure 4)

- Scissors reflex: irregular retinoscopic reflex

- Egg-shaped mires on keratometry

- Inferior corneal steepening: inferior-superior dioptric asymmetry (I:S) value >1.4

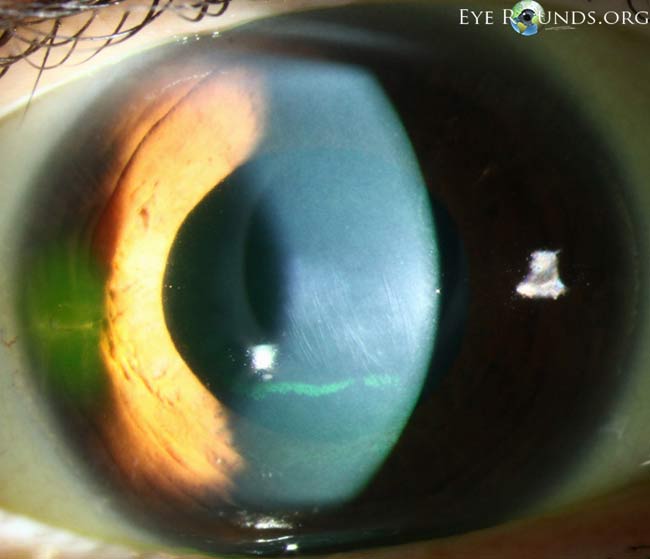

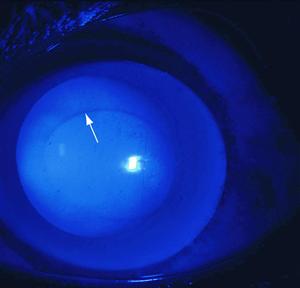

- Fleischer ring: iron ring around base of cone (Figure 5)

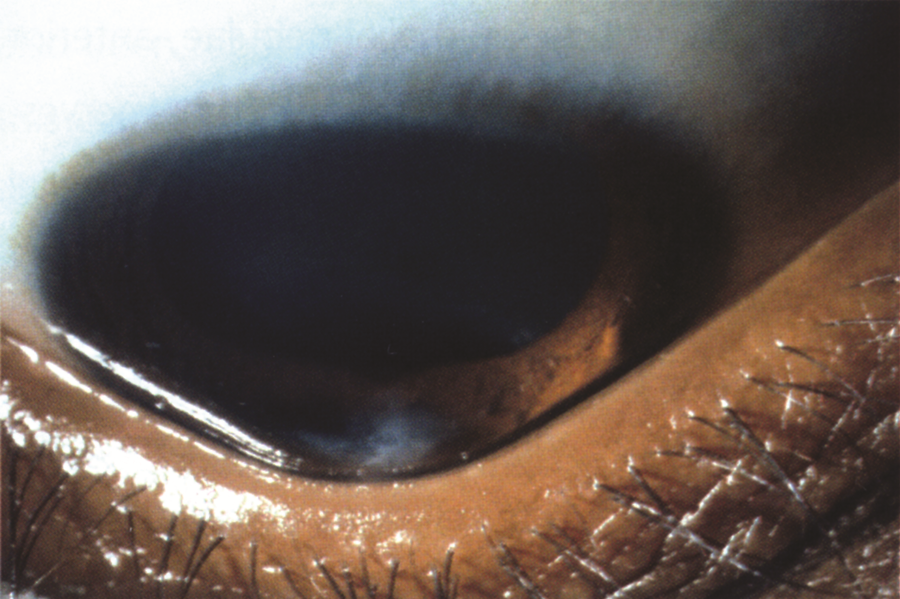

- Munson sign: bulging of lower lid on downgaze (Figure 6)

- Corneal scarring

- Acute corneal hydrops secondary to Descemet membrane rupture

- Rizutti sign: conical nasal reflection with temporal illumination (Figure 7)

Symptoms

- Progressive decreased vision/diplopia

- Acute corneal hydrops

- Sudden vision decrease

- Pain

- Red eye

- Photophobia

- Tearing

Management

Evaluation

- Manifest keratoconus is easily detected clinically by slit-lamp examination and corneal curvature readings.

- Corneal topography is used to identify earlier stages of keratoconus.

- Progression of keratoconus is important for both the ophthalmologist and the patient to anticipate by way of changes in visual acuity. Progression is best evaluated by analyzing serially collected quantitiative measures of corneal topography (eg, elevation, pachymetry, curvature).

- New technology combines slit-scanning (projective) and Placido disk (reflective) based technology to generate elevation maps as well as corneal thickness measurements across the entire cornea (Sahin et al, 2008).

Laboratory Evaluation

- Assessment of heritable disease associated with keratoconus:

- Down syndrome

- Leber congenital amaurosis

- Ehlers-Danlos, Marfan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta

- Treatment of mild to moderate keratoconus:

- The goal of treatment is to achieve functional visual acuity.

- To this end, spectacles and soft toric contact lenses can be used. However, rigid gas permeable lenses are required in most cases to correct the irregular corneal astigmatism.

- Corneas that are too irregular or too steep and cannot tolerate hard lenses can be fitted with specialty contact lenses developed for keratoconus (eg, custom-designed contact lenses, semi-scleral contact lenses, piggyback lenses, scleral lenses)

- Intracorneal ring segments can be used in patients with a clear central cornea and corneal thickness of >450 µm where the segments are inserted. Most patients have flatter corneas and easier use of lenses after insertion. This procedure might delay the need for corneal transplant, but there is no evidence that disease progression is altered.

- Treatment of moderate to severe keratoconus:

- Eyes that cannot tolerate contact lenses or do not have acceptable vision (eg, corneal scarring present) can seek other surgical alternatives.

- Penetrating keratoplasty (PK) is the standard surgical treatment with a history of high rate of success, safety, and efficacy. The main risks of PK are infection, graft rejection, and traumatic rupture at wound margin.

- Anterior lamellar keratoplasty can be attempted. This procedure leaves the endothelium, Descemet membrane, and some stroma intact. Thus, there is less risk of traumatic rupture of the globe at the wound margin and faster visual rehabilitation. Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) is a different techniques used for anterior lamellar keratoplasty. These procedures can be technically challenging and may require conversion to PK.

- Many patients after keratoplasty still require hard lenses to achieve best vision.

- UVA/riboflavin collagen cross-linking (CXL) of the cornea is a non-FDA approved procedure for keratoconus. Introduced by Wollensak et al for the treatment of progressive keratoconus, it increases the biomechanical strength of the cornea by 300%. So far, studies of CXL only and CXL in combination with refractive surgery have demonstrated that it may halt and even reverse the progression of keratoconus.

Table 2 lists suggested therapy according to the severity of keratoconus.

| Table 2. Keratoconus Therapy |

| Keratoconus Severity |

Suggested Therapy |

| Mild |

Spectacles

Soft contact lenses

Hybrid or hard contact lenses |

| Moderate |

If cannot tolerate or fails use of contact lenses:

Intracorneal ring segments + contact lenses

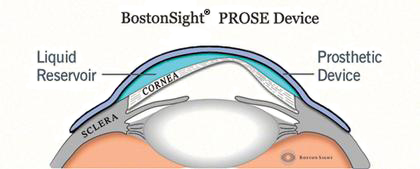

PROSE device (Figure 8)

Scleral lenses

Hybrid or hard contact lens |

| Severe |

If cannot tolerate or fail above therapies or if visually significant corneal scarring:

Partial-thickness corneal transplant (Figure 9)

Full-thickness corneal transplant (Figure 10) |

| Additional Therapy |

If mild to moderate symptoms with signs of progression:

Corneal collagen crosslinking |

| Acute corneal hydrops |

Artificial tears ointment 2 times a day

Cycloplegic agent

Brimonidine 0.1% bid (if IOP > 20)

Bacitracin ointment 4 times a day

Glasses or shield for protection from trauma and rubbing

Ophtalmic sodium chloride solution

Topical corticosteroid

Topical antibiotics |

CASE STUDY

History of Present Illness

A 15-year-old boy came to the emergency room with his mother. He had been complaining of a foreign body sensation in the right eye for 2 days. Further history revealed that he underwent a corneal transplant of the right eye around 1 year ago. His older brother had also had a corneal transplant.

Examination

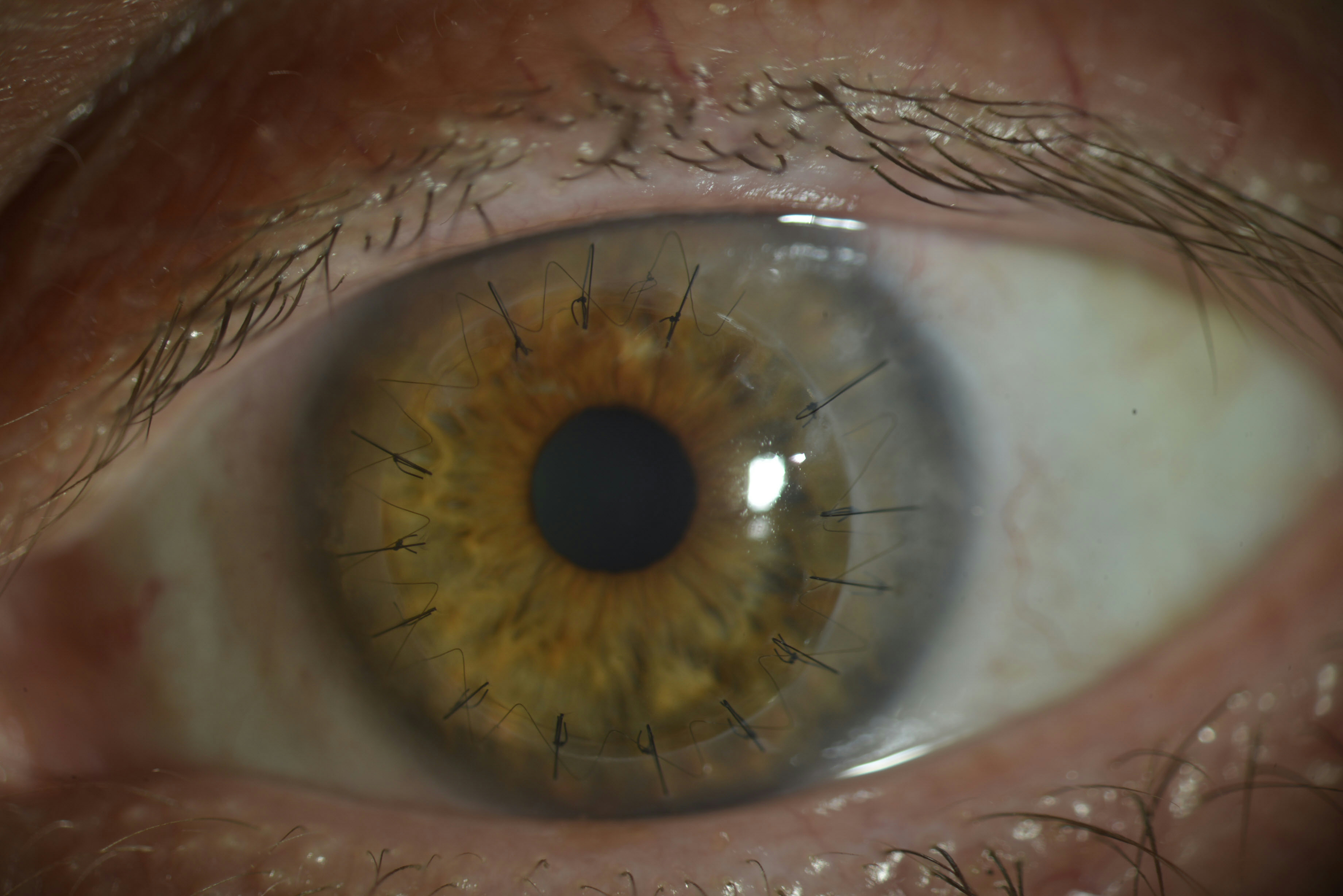

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/30 in the right eye was 20/30 and 20/200 in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination showed that the right eye had a clear corneal graft with a single exposed suture that caused minimal congestion at the site and needed to be removed. The remainder of examination of the right eye appeared otherwise normal. The left eye showed a conical-shaped cornea with corneal scarring at the centre of the cone and visible corneal nerves at the peripheries (Figure 11). The anterior chamber was deep. The rest of the examination of the left eye was normal.

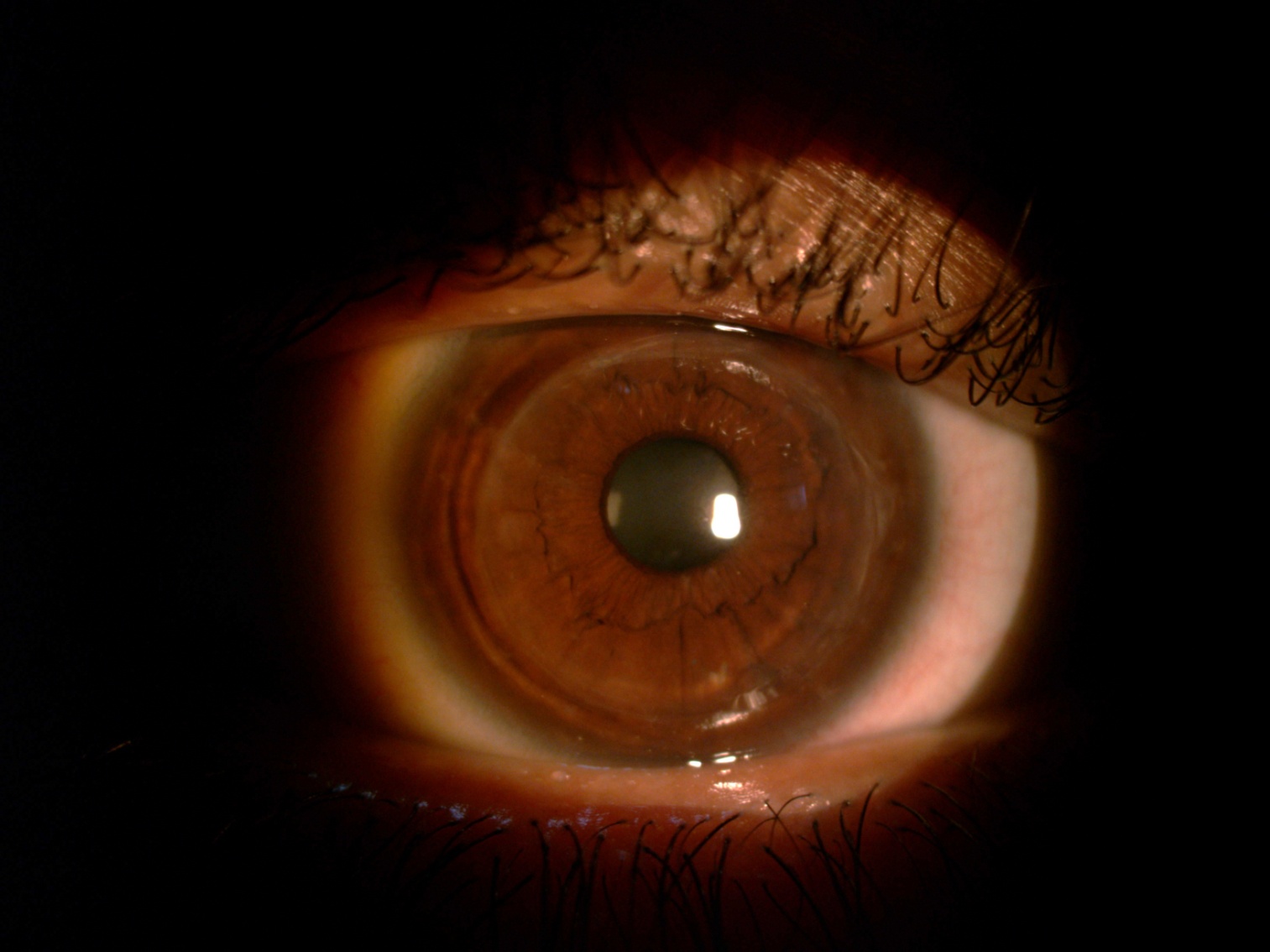

Management

The exposed suture was removed, and the patient was kept on a topical mixture of antibiotic and corticosteroid. He was scheduled for penetrating keratoplasty of the left eye, which was done around a month later (Figure 12). His best-corrected visual acuity 1 month after surgery was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye.

IMAGE LIBRARY

Differential Diagnosis

Figure 1. Pellucid marginal degeneration. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Pathophysiology/Definition

Figure 2. Oblique slit-beam view of a patient with keratoconus shows inferiorly decentered protrusion of the cornea. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Figure 3. Atopic eyes. Allergic contact dermatitis secondary to topical ophthalmic medication. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org).

Signs / Symptoms

A.

B.

C.

Figure 4. Examples of Vogt striae (A–C). These vertical tension lines may be asymmetric depending on the degree of keratoconus in each eye. The striae can temporarily disappear with external pressure to the globe. (Reproduced, with permission, from. Kirkpatrick CA. Vogt’s striae in keratoconus. Photographs by Toni Venckus, CRA. EyeRounds Online Atlas of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 5. Keratoconus showing a Fleischer ring (arrow) using cobalt blue light. (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.)

Figure 6. Munson sign. A V‑shaped curvature of the lower lid margin on downgaze is termed Munson sign. (Reproduced, with permission, from Kılıç A, et al. “Advances in the Surgical Treatment of Keratoconus.” Focal Points: Clinical Modules for Ophthalmologists. American Academy of Ophthalmology, No. 3, 2012.)

Figure 7. Rizzutti sign. A penlight is shone on the temporal side and a sharply focused conical reflection is obtained on the nasal cornea (arrow). (© 2015 American Academy of Ophthalmology, www.aao.org.).

Figure 8. PROSE device. (Reproduced, with permission, from Boston Foundation for Sight.)

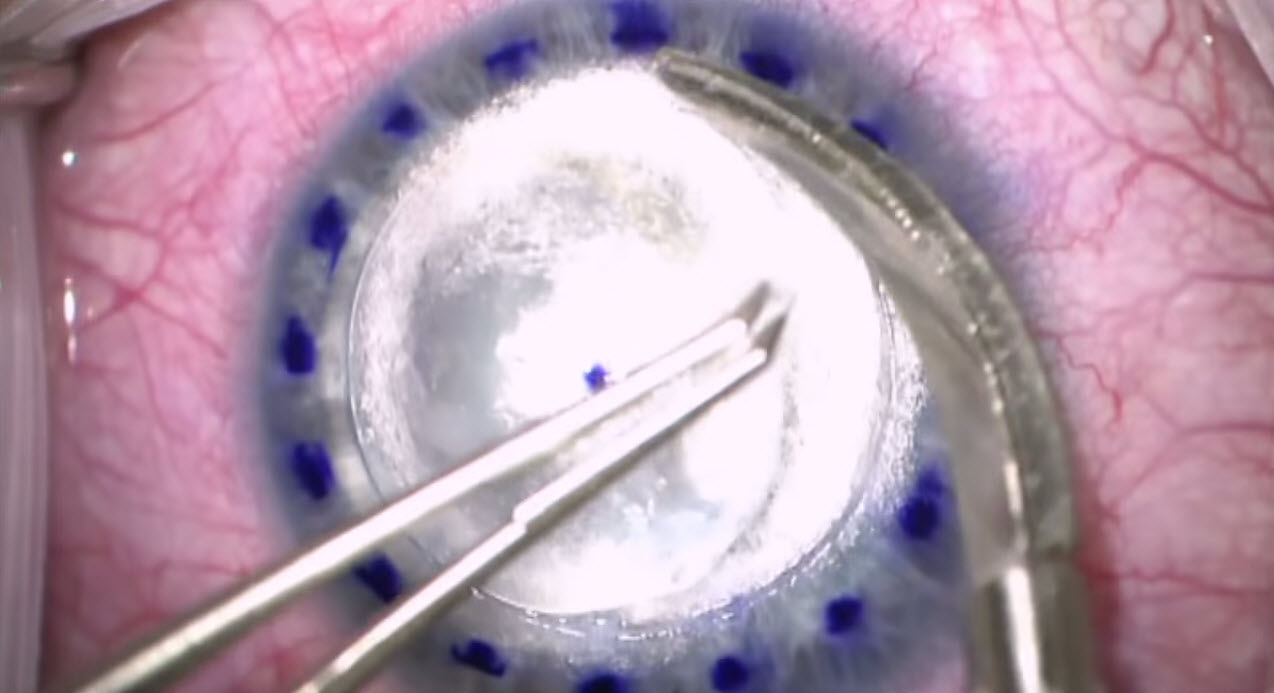

A.

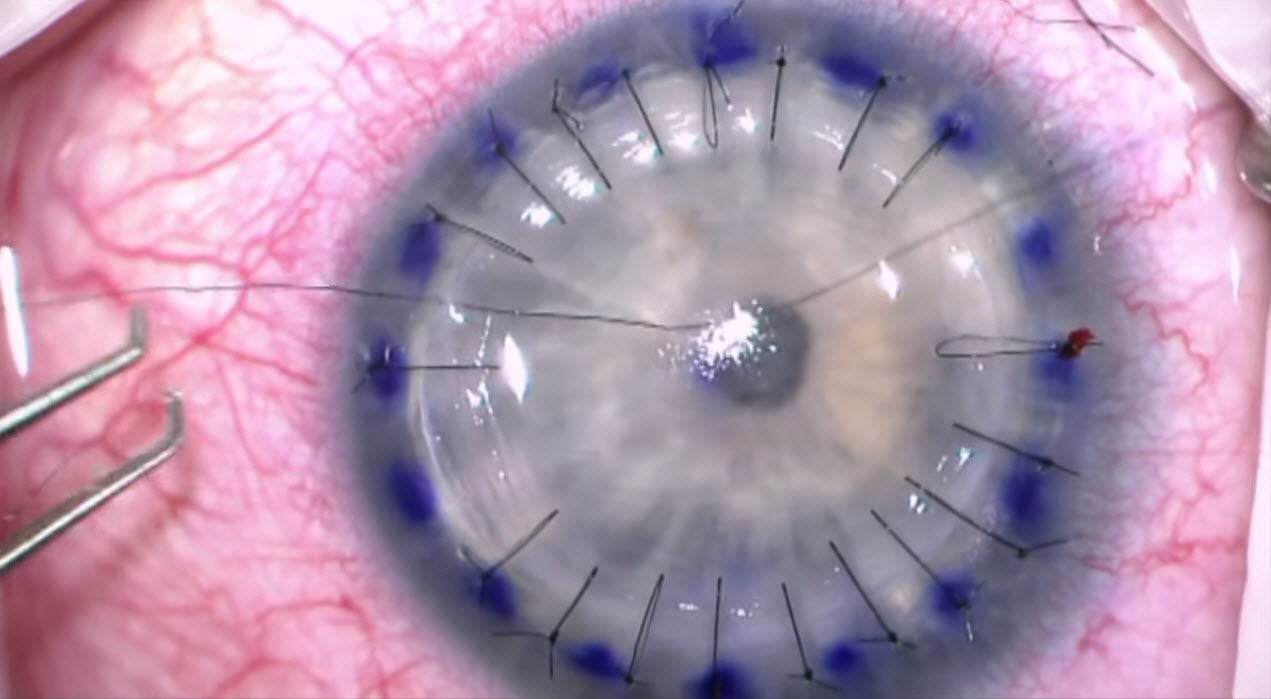

B.

Figure 9. Partial-thickness corneal transplant. A. Preparing to resect the anterior stroma. B. Grafting completed, with interrupted 10-0 nylon sutures in place. (Reproduced, with permission, from video Big bubble DALK technique. Video by Matt Ward, MD, and Mark Greiner, MD. EyeRounds Online Atlas of Ophthalmology.)

Figure 10. Full-thickness corneal transplant. (Courtesy of Soledad Cortina, MD.)

Case Study

Figure 11. Keratoconus in the left eye. (Courtsy of Dr. Ebtisam Al Alawi.)

Figure 12. Post keratoplasty. (Courtsy of Dr. Ebtisam Al Alawi.)

REFERENCES

Al-Towerki AE, Gonnah el-S, Al-Rajhi A, Wagoner MD. Changing indications for corneal transplantation at the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital (1983–2002). Cornea. 2004;23(6):584–8.

Assiri AA, Yousuf BI, Quantock A J, Murphy P J. Incidence and severity of keratoconus in Asir province, Saudi Arabia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(11):1403–6.

Basic and Clinical Science Course. External Disease and Cornea Section 8. 2011–2012. San Francisco: American Academy of Opthalmology; 2011: 296–300.

Bialasiewicz A, Edward DP. Corneal ectasias: study cohorts and epidemiology. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013;20(1):3–4.

Claesson M, Armitage WJ. Corneal grafts at St John Eye Hospital, Jerusalem, January 2001-November 2002. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(7):858–60.

Cozma I, Atherley C, James NJ. Influence of ethnic origin on the incidence of keratoconus and associated atopic disease in Asian and white patients. Eye (Lond). 2005;19(8):924–5.

Cullen JF, Butler HG. Mongolism (Down’s syndrome) and keratoconus. Br J Ophthalmol. 1963;47:321–30.

Davanger M. Studies on the pseudo-exfoliation material. AlbrechtVvon Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1978;208(1–3):65–8.

Friedberg M, Rapuano C. Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 5th ed. New York: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2008.

Frucht-Pery J, Shtibel H, Solomon A, Siganos CS, Yassur Y, Pe'er J. Thirty years of penetrating keratoplasty in Israel.Cornea. 1997;16(1):16–20.

Georgiou T, Funnell CL, Cassels-Brown A, O’Conor, R. Influence of ethnic origin on the incidence of keratoconus and associated atopic disease in Asians and white patients. Eye (Lond). 2004;18(4): 379–83.

Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Yazdani N, et al. The prevalence of keratoconus in a young population in Mashhad, Iran. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014;34(5):519–27.

Ihalainen A. Clinical and epidemiological features of keratoconus genetic and external factors in the pathogenesis of the disease. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1986;178:1–64.

Jonas J B, Nangia V, Matin A, Kulkarni M, Bhojwani K. Prevalence and associations of keratoconus in rural maharashtra in central India: the central India eye and medical study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(5):760–5.

Kennedy R H, Bourne WM, Dyer JA. A 48-year clinical and epidemiologic study of keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;101(3): 267–73.

Kim S-H, Mok J-W, Kim H-S, Joo CK. Association of −31T>C and −511 C>T polymorphisms in the interleukin 1 beta (IL1B) promoter in Korean keratoconus patients. Mol Vis. 2008;14:2109–16.

Kok YO, Tam GF, Loon SC. Review: keratoconus in Asia. Cornea. 2012;31(5):581–93.

Kotb AM, Hantera M. Efficacy and safety of Intacs SK in moderate to severe keratoconus. East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013; 20(1):46–50.

Mahmood MA, Wagoner MD. Penetrating keratoplasty in eyes with keratoconus and vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2000;19(4):468–70.

McKibbin M, Ali M, Mohamed MD, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation for leber congenital amaurosis in Northern Pakistan. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(1):107–13.

McMahon TT, Szczotka-Flynn L, Barr JT, et al. A new method for grading the severity of keratoconus: the Keratoconus Severity Score (KSS). Cornea. 2006;25(7):794–800.

Millodot M, Shneor E, Albou S, Atlani E, Gordon-Shaag, A. Prevalence and associated factors of keratoconus in Jerusalem: a cross-sectional study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2011;18(2): 91–7.

Nielsen K, Hjortdal J, Aagaard Nohr E, Ehlers N. Incidence and prevalence of keratoconus in Denmark. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85(8):890–2.

Owens H, Gamble G. A profile of keratoconus in New Zealand. Cornea. 2003;22(2):122–5.

Pearson AR, Soneji B, Sarvananthan N, Sandford-Smith J H. Does ethnic origin influence the incidence or severity of keratoconus? Eye (Lond). 2000;14 ( Pt 4):625–8.

Rabinowitz YS. Keratoconus. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42(4):297–319.

Sahin A, Yildirim N, Basmak H. Two-year interval changes in Orbscan II topography in eyes with keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(8):1295–9.

Sundaresan P, Vijayalakshmi P, Thompson S, Ko AC, Fingert JH, Stone EM. Mutations that are a common cause of Leber congenital amaurosis in northern America are rare in southern India. Mol Vis. 2009;15:1781–7.

Tanabe U, Fujiki K, Ogawa A, Ueda S, Kanai A. [Prevalence of keratoconus patients in Japan]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1985;89(3):407–11.

Waked N, Fayad AM, Fadlallah A, El Rami H. [Keratoconus screening in a Lebanese students’ population]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2012;35(1):23–9.

Wollensak G. Crosslinking treatment of progressive keratoconus: new hope.Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17(4):356–60.

Ziaei H, Jafarinasab MR, Javadi MA, et al. Epidemiology of keratoconus in an Iranian population. Cornea. 2012;31(9):1044–7.