As my senior founding partner always says, “The only sure way to avoid any complications as a surgeon is to stop operating.” We will all inevitably experience the sinking feeling of causing a tear in the posterior capsule (PC). Appropriately managing these complications is a hallmark of a skilled, experienced anterior segment surgeon. Fortunately, with modern operative technologies in cataract surgery, the patient can more often than not experience excellent long-term outcomes.

Here are six surgical pearls for when the capsule breaks:

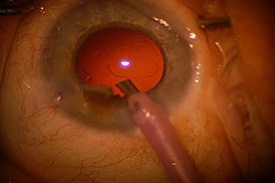

Photo courtesy of University of Iowa, eyerounds.org.

1. Slow down and control the anterior chamber. The first thing to do when you suspect a PC tear is to freeze — not stop — what you are doing by keeping positive pressure in the anterior chamber. Keep the phaco or irrigation/aspiration hand piece in the eye and maintain irrigation. Then, with your second hand, instill enough dispersive viscoelastic to keep the anterior chamber formed

Only then should you remove the phaco or irrigation/aspiration hand piece from the eye. It is natural for the beginning surgeon to want to remove everything from the eye immediately when you sense something wrong. You must learn to fight this urge. These essential early maneuvers will greatly prevent further vitreous loss. Once the anterior chamber is stabilized, you can carefully evaluate the situation and plan how to manage the complication without any time pressure.

2. Have a team plan and stay calm. Complications in surgery are inevitable but hopefully infrequent. It is natural for us to be uncomfortable doing things we do not do routinely, especially in highly stressful situations. By preparing a PC rupture protocol that you have on file with the OR staff, you can significantly reduce the type of hectic environment that often ensues after a complication. For example, when I say the keyword “A-Vit” to my OR staff, they automatically know to urgently get more dispersive viscoelastic, switch to the anterior vitrectomy setting on the phaco machine, pull all additional instruments, prepare and dilute intracameral steroids for vitreous visualization and Miochol for miosis and pull the backup three-piece IOL.

Often, the patient will not be aware anything unusual is happening. Remember that you are the leader in the OR. The staff will mimic your behavior. If you are scared, they will act the same. You must stay calm and in control.

3. See the V. Seeing what you are doing always helps in intraocular surgery. Excellent visualization of vitreous in the anterior chamber can easily be achieved with preservative-free triamcinolone. A dilution of 10:1 is easy to inject in the anterior chamber and highlights the vitreous well. Repeat often, especially at the end of anterior vitrectomy when most of the viscoelastic has been removed, to ensure that the anterior chamber is clear of vitreous.

4. Don’t hesitate with anterior vitrectomy. Proper control of the anterior chamber during anterior vitrectomy begins with having a closed system. Suture the main wound. Create a second paracentesis and perform bimanual anterior vitrectomy with separate vitrectomy and infusion hand pieces. By always maintaining irrigation anterior to the vitrector, you use fluidics to your advantage in order to prevent more vitreous prolapse.

As efficient cataract surgeons, we are always conscientious of limiting phaco energy. As a result, we can be “light on the foot pedal.” We must fight this natural tendency to be reserved and hesitant with anterior vitrectomy. Typical foot pedal positions for the anterior vitrectomy setting should be 1 irrigation 2 vitrectomy cutting 3 aspiration. Thus, cut the vitreous initially before aspirating and reducing intact vitreous traction. Modern phaco platforms have cut rates comparable to traditional vitrectomy units used by our retinal colleagues. Set the cutting for the highest rate and floor it. This aggressive approach actually reduces vitreous traction and greatly speeds up vitreous removal.

5. Determine the degree of cortical removal. It is important to remove as much cortex as possible to decrease short-term and long-term postoperative inflammation. Cortical removal can be performed two ways: manual aspiration with a 27-gauge cannula on a syringe or with a bimanual automated technique using the anterior vitrectomy hand piece.

The proper foot pedal settings for bimanual removal should be 1 irrigation 2 aspiration 3 vitrectomy cutting. The irrigation and aspiration are the initial functions when stepping down on the foot pedal. The vitrectomy cut function is reserved to pushing down deeper into the foot pedal. You should only engage it when vitreous is in the way of the cortical removal. Be careful and attempt to preserve as much capsule as possible. Avoid the aggressive foot pedal technique used in anterior vitrectomy. There is very fine control with manual aspiration, but it is time consuming. It is ideal for small PC tears with little to no vitreous loss.

6. Appropriately place the IOL. After anterior vitrectomy and cortical removal, carefully assess the extent of the posterior capsular tear to determine which IOL placement locations are appropriate.

- In-the-bag IOL placement is safe with small posterior capsular tears if they are circular or made circular with a posterior capsulorrhexis.

- Larger tears with good anterior capsular and zonular support are best resolved with a three-piece IOL placed in the sulcus. You should never place a one-piece acrylic IOL in the sulcus, as this will lead to iris chafing and chronic, recurrent inflammation. If possible, use a round-edged three-piece IOL, as this will also minimize chafing.

- If the anterior capsulorrhexis is smaller than the optic, optic capture in the bag will result in the most stable long-term configuration.

- If there is poor zonular support, you may need an anterior chamber IOL or various scleral- or iris-fixation techniques. If the view is clear and you are comfortable doing so, move forward with the more complex IOL technique. Otherwise, consider leaving the patient aphakic. Planning for a secondary IOL implant procedure in a controlled, scheduled operative setting is often better for the nerves of both patient and surgeon.

Remember this adage: “If you don’t have any complications operating, either you are lying or you are not doing enough surgery.” The competent surgeon does not fear complications but understands why they occur and learns from them, evolving his or her technique to avoid repeating history.

* * *

About the author: Edward Hu, MD, PhD, is an experienced high-volume refractive cataract surgeon at the Illinois Eye Center. He performs 25 to 40 cataract surgeries a week and currently has a PC tear rate of 0.001 percent — significantly lower than that from early on in his career.