The conversation with the attending lasted only an hour, but at the end of the humiliating session, the third-year medical student had begun a spiral downward that would take him through a long bout of depression and to the brink of suicide. Not until his ophthalmology residency would John Cropsey, MD, fully return to himself.

Yet less than 10 years later, the young ophthalmologist had so distinguished himself through eye care in Kenya and Burundi that he received the Academy’s inaugural Artemis Award at AAO 2014 in Chicago. In an interview with YO Info, Dr. Cropsey, 35, explained how he made such a turn-around and described the joy of his work in East Africa, where he teaches at a university in Burundi’s capital.

The child of a missionary doctor, Dr. Cropsey grew up in Togo, West Africa. By high school, he knew he, too, wanted to be a doctor. “Basically I told God, ‘I’d like to be a medical missionary in Africa,’” he said. “‘If you want me to be a plumber instead, let me know.’”

An Early Crisis

Early in his career planning, Dr. Cropsey resolved to “do [medicine] with a balanced life.” But three years into medical school at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, a particularly difficult encounter with an attending left him shaken to his core.

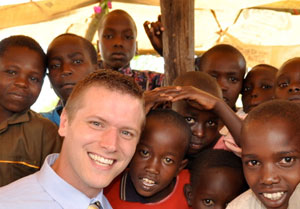

Dr. Cropsey during his work in Kenya.

For a one-month rotation early in his clinical experience, Dr. Cropsey traveled to a private hospital. By chance, he was the only student scheduled for rotation that month.

A few days in, a senior doctor invited Dr. Cropsey to breakfast. After accepting in pleased surprise, Dr. Cropsey was stunned by the conversation that followed. “He spent the next hour personally berating me and threatening my medical career,” he said.

“It never happened again, but I was always terrified” that it would. “Self-doubt started keeping me up at night and my stress levels ramped up,” Dr. Cropsey said. “I was expecting all of my rotations to be shamed-based learning exercises.”

In the months that followed, he began to struggle with low-grade depression and insomnia, then “crashed and burned” during his internship.

Part of the depression Dr. Cropsey credited to the pressures of medical training in general, but also to his sense of inadequacy. “You feel like you’re an imposter. Somehow you slipped through the academic cracks.”

Various studies have shown higher rates of depression and burnout among medical students. Physicians also commit suicide more frequently than the general population.

In the midst of self-doubt, Dr. Cropsey said he didn’t “really believe the success that I’ve had is legitimate.”

A patient embraces Dr. Cropsey after a successful surgery.

He credits his family, Christian faith and a supportive training program with helping him get through.

At the worst, when he was suicidal, Dr. Cropsey said, “I was 100 percent sure I was dragging everyone down … that I was just dead-weight.” But no matter what he said or thought, his loved ones had an answer. “It was my wife telling me over and over that she loved me, she would never leave me. … People having rational responses to my irrational logic.”

At one point, his program reassigned him so that he didn’t have direct patient care responsibilities, but could still work toward meeting its internship requirements. His father drove him to and from his elective. A compassionate senior resident also had a significant role in getting him through the worst of it.

In the end, Dr. Cropsey only had to take one sick day during his internship year. However, not until his residency at Wills Eye Institute did he finally come out of the depression completely.

A 2010 JAMA study found that medical students stigmatized depression, but Dr. Cropsey advised those battling it to share their struggle with others, as he did. “Surround yourself with people who care about you and love you.”

He also recommended professional help. “When you get into depression … the thoughts you’re thinking about yourself aren’t true, but you’re sure they are,” he said.

“You need people to surround you who love you and can speak truth into your life, can speak hope into your life. When you lose hope, that’s bad.”

“You’re not going to believe any of what they say … but you need to hear those people. … That little glimmer of hope might get you through another day.”

He also encouraged physicians to think about “where we are finding our value” as people. “You have to ask yourself, where is my identity rooted?”

For Dr. Cropsey, his struggle with depression “really showed me that my identity was wrapped in what people thought of me, how smart I was, how things were going academically and not rooted in the right stuff,” he said.

Ultimately, he said his Christian faith has helped him become more resilient. “God’s chosen to love me just as I am. That’s all I really need to know at the end of the day.”

After Despair, Adventure

Dr. Cropsey said his faith also spurred him to move his family overseas to help meet eye care needs in underserved parts of Africa. After his residency at Wills, he did a post-residency program in Bomet, Kenya, with Samaritan’s Purse.

Working with Tenwek Hospital in Kenya, Dr. Cropsey helped establish the first corneal-transplant program in the area and developed training programs for community eye care providers. During his time at Tenwek, the eye unit consisted of 15 Kenyan staff members and, for 14 months, one ophthalmologist -- Dr. Cropsey. In a 2010 interview, he told YO Info they were “the main referral center for roughly 10 million people.”

After a fruitful season in Kenya, however, Dr. Cropsey decided to relocate to Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi. He’s now a professor at Hope Africa University, where he leads a team of nearly 30 expatriot missionaries partnering to develop the medical school. He spends four days a week doing surgery and teaching, and one day on administrative duties.

Tips for Short-Term Service

• “Play to your strengths.” Check in advance to be sure what type of patient care and staffing the trip would involve. “If [you’re] a phaco guy, [you] better be sure you can do phaco with what they have.”

• Work with a strong national partner on the ground. “You have to have local buy-in to make a lasting impact. Free is terrible. It undermines sustainable eye care models in the entire region.”

• Transfer skills. While a short-term trip is a great way to share techniques with colleagues there, it’s also a chance to learn. Dr. Cropsey said he’s learned a lot from Kenyan colleagues about MSICS techniques.

• Learn in advance. Many cataracts, for instance, “should’t be phaco-ed” in a majority world setting. “There’s times when MSICS [explanation] … would be better.” Dr. Cropsey recommended doing a course on small-incision procedures before taking a trip.

• Go back to the same place. “Don’t do medical tourism.” By going back repeatedly, you’ll develop relationships and trust – and help build local capacity.

|

Planning for the Long Term

His patients include a mix of cataract and glaucoma cases. During an interview at AAO 2014 in Chicago, he said Burundians currently had to leave the country to get care for conditions like diabetic retinopathy. Since most of his patients make less than $1/day, he said they can’t afford such travel. But during the Chicago meeting, Dr. Cropsey made arrangements to get the first functioning laser in the country.

Although he said Burundians don’t eat a Western diet, diabetes is increasing in cities. “When they get diabetes, it’s poorly managed,” he said. He’s seen cases of “very aggressive diabetic retinopathy.”

Thanks to the laser, and a vitrectomy machine donation, Hope Africa University has begun retinal care.” We still lack some key instrumentation (retina grade microscope, functioning BIOM, cryo etc),” Dr. Cropsey said in an email, “but we can do a lot now.”

Despite what equipment may cost, Dr. Cropsey generally prices surgeries based on how much they improve the patient’s vision.

2015 Artemis Award

Know an exceptional YO? Society leaders, department chairs and program directors can nominate someone for this year’s award.

“Things that aren’t going to change vision, I price a lot lower,” he said. Although Dr. Cropsey said their cataract prices (roughly $45 in U.S. dollars) “feel a little high,” it’s more proportional to the result.

That way, “You’re not going to have people going back to the village saying, ‘I just gave up two goats’ worth of income, and I don’t see.’ They’re going to go back and say, ‘I paid two goats, and it was totally worth it.’”

Although his U.S. supporters could totally underwrite surgeries, Dr. Cropsey said that wouldn’t be sustainable long-term.

“I’m trying to think 20 years ahead,” Dr. Cropsey explained. If patient fees can’t cover most of a hospital’s expenses, how could the facility support the Burundian ophthalmologists he hopes will someday take over?

Such long-term thinking is one reason Wills Eye Institute nominated Dr. Cropsey for the Artemis Award. “We are so proud of John at Wills,” said Julia Haller, MD, chair of the Wills ophthalmology department. “He epitomizes everything we admire in a caring, committed young ophthalmologist -- focused on excellence and making the world a better place.”

Dr. Cropsey received the honor, which the Academy’s Senior Ophthalmologist Committee gives to a young ophthalmologist for exemplary service, at AAO 2014 in Chicago.

* * *

About the author: Christi A. Foist is YO Info’s managing editor and a communications manager for the Academy.