Alongside a thorough history and examination, choosing to image an adult patient with strabismus can be a lifesaving decision.

Imaging may help you make a diagnosis, but it can also help rule out other dangerous conditions in the differential and help lay out a surgical plan.

After a detailed history, a complete ophthalmic exam needs to be completed with special attention to the pupillary exam, sensorimotor examination with alignment in multiple gazes, along with versions and ductions.

But when should you image and when should you hold back? Here are some tips to help guide you.

1. Pay attention to cranial neuropathies (third, fourth, sixth)

- Etiologies include ischemia, inflammation, infection, compression, congenital cranial neuropathies and neuromuscular junction disorders.

- Patients younger than 50 with an acute-onset cranial nerve palsy warrant imaging, usually a contrast-enhanced MRI.

- Patients over 50 without vasculopathic risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking history, etc.) should also undergo imaging.

- However, patients over 50 with vasculopathic risk factors and an isolated cranial neuropathy without other neurologic signs or symptoms are more controversial cases. No consensus exists as to whether such patients need immediate imaging or whether you should simply wait for resolution first.

- Be sure to urgently image all third nerve palsies, regardless of pupillary involvement without a previously known diagnosis or etiology. Get an MRA to evaluate for an aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery.

- Fourth nerve palsies with a less acute presentation and large fusional vertical amplitudes are likely longstanding and do not require urgent imaging.

2. Rule out other signs and symptoms that warrant further investigation

Take a complete history of the following elements:

- Loss of vision

- Loss of visual field

- Headache

- Weakness, numbness of face or extremities

- Dizziness

- Eye pain

- Trauma (recent or remote, head or orbital)

- Surgical history (ocular surgery, periocular, neurosurgical)

- Don’t forget about Giant Cell Arteritis:

- Sudden, painless vision loss, jaw claudication, scalp tenderness, headache, proximal muscle/joint pains, fever, weight loss

You should also complete an exam that covers each of the following:

- Vision

- Pupillary exam (in light and dark): anisocoria, or afferent pupillary defect present?

- Visual fields

- Nystagmus

- Proptosis or other orbital signs (thyroid eye disease or orbital tumor)

- Optic nerve: papilledema, optic atrophy

- Variable strabismus, ptosis, fatigable (rule out myasthenia gravis)

3. Know when to say no to imaging

- History of long-standing, stable strabismus

- History of prior strabismus surgery without recent changes

- Recent ophthalmic surgery (retina, glaucoma, retrobulbar block, pterygium surgery) that explains the strabismus

- Previous imaging before referral (commonly done)

- Known diagnoses (thyroid eye disease, myasthenia) that explain the strabismus

- Sagging Eye Syndrome: Older patients with divergence paralysis esotropia and normal horizontal ductions/saccades or small vertical deviations and no neurologic complaints may represent sagging eye syndrome from age-related orbital connective-tissue degeneration.

- Additional signs include superior sulcus deformity, aponeurotic ptosis with high eyelid crease or history of blepharoplasty.

- High-resolution MRI of the orbits can help confirm the diagnosis, if in doubt, and will show symmetric or asymmetric downward displacement of both lateral rectus pulleys.

4. Get help with complex strabismus cases

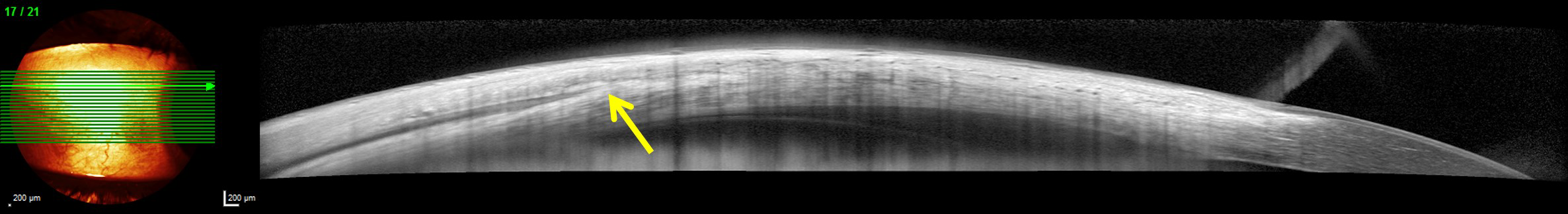

Standard MRI and CT scans can be beneficial in these cases. However, certain situations may merit use of dynamic MRI, high-resolution MRI, ultrasound biomicroscopy or anterior segment optical coherence tomography (see below).

When appropriate, these scans can give additional information and can help formulate a treatment approach.

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (Spectralis Anterior Segment Module, Heidelberg, Germany) of a right lateral rectus muscle showing the muscle insertion (arrow). This technique can be used to identify recti muscles that have previously been recessed.

* * *

About the author: Matthew S. Pihlblad, MD, is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh specializing in pediatric ophthalmology and adult strabismus. He also practices at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC in Pittsburgh. Dr. Pihlblad completed his medical degree at the West Virginia University School of Medicine, residency in ophthalmology at the University at Buffalo and fellowship training in pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus at the Jules Stein Eye Institute, UCLA.