Knowing when to refer a patient to the retina clinic can be challenging. Many retina conditions have subtle findings on optical coherence tomography (OCT) which adds to the difficulty.

The following are three retina conditions that are commonly encountered in a general ophthalmology practice whose OCT findings can lead one to ask: Should I refer this — or not?

Epiretinal Membrane

|

|

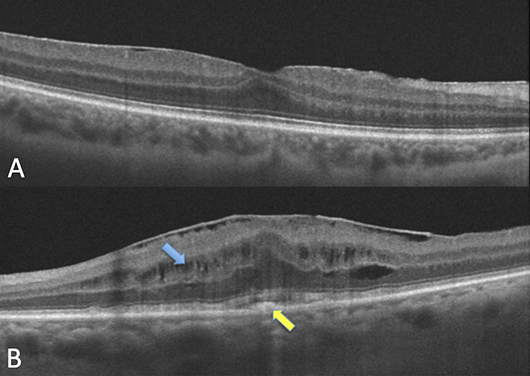

FIGURE 1. A: There is a thin epiretinal membrane with minimal distortion of the retinal contour. B: The epiretinal membrane is associated with cystic changes (blue arrow), retinal thickening, loss of the foveal contour, and the presence of subfoveal hyperreflective material (yellow arrow).

|

An epiretinal membrane (ERM) is a semitranslucent, fibrocellular tissue found on the inner surface of the retina. Most cases are idiopathic, while others are related to vascular disease, inflammation or trauma. ERMs are one of the most common reasons to refer a patient to a vitreoretinal surgeon.

In the past, ophthalmologists waited until patients’ decrease in vision affected their daily lives before referring. However, the threshold for surgery has changed over the past 20 years. Small gauge vitrectomy along with wide-angle viewing systems have lowered the risk of vitreoretinal surgery. They also have led to better anatomical outcomes in mild cases of ERM.

The determination to proceed with surgery is made on a case-by-case basis. Some vitreoretinal surgeons may recommend surgery to a patient whose visual acuity is 20/30 but is bothered by the associated metamorphopsia, while others may observe a patient who is 20/60 but asymptomatic. Other considerations may include the potential for progression, the presence of subretinal fluid and the status of the contralateral eye.

When looking at the OCT scan of a patient with an ERM, it is important to see if the ERM is causing only inner retinal changes or whether outer retinal disruption (usually associated with visual loss) is observed. In patients with only inner retinal changes and good visual acuity, the presence of worsening metamorphopsia warrants a referral. Others can be observed in your clinic.

Vitreomacular Adhesion vs. Vitreomacular Traction

|

|

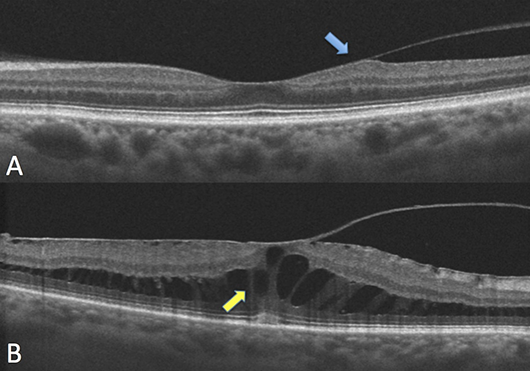

FIGURE 2. A: Note the vitreomacular adhesion with mild traction on the temporal retina (blue arrow), but the retinal layers are generally preserved. B: Vitreomacular traction associated with cystic spaces (yellow arrow) and loss of foveal contour.

|

Vitreomacular adhesion (VMA) is a perifoveal vitreous detachment in the presence of persistent foveal attachment observed on OCT. VMA represents a single stage of impending vitreous detachment without retinal abnormalities. Patients with VMA do not report symptoms. In most cases, VMA spontaneously resolves without affecting the retina. VMA can be monitored conservatively with an annual dilated fundus examination and OCT.

Vitreomacular traction (VMT) is the abnormal attachment of the vitreous to the macula causing a structural abnormality. VMT occurs when there is an imbalance between vitreous liquefaction and the separation of the vitreous cortex from the retina. This results in an anomalous posterior vitreous detachment that exerts a tractional force on the underlying retina. VMT can distort the contour of the retina and lead to macular edema. In some cases, VMT can cause a macular hole.

Unlike VMA, patients with VMT typically have visual symptoms including decreased visual acuity and metamorphopsia. Cases of VMT that are asymptomatic and do not have a macular hole can be observed closely. However, if there is progression of the traction on OCT or symptoms worsen, referral to a vitreoretinal surgeon should be considered. Other reasons to refer include recalcitrant macular edema, an impending macular hole, or history of macular hole in the fellow eye.

Drusen vs. Pigment Epithelial Detachment

|

|

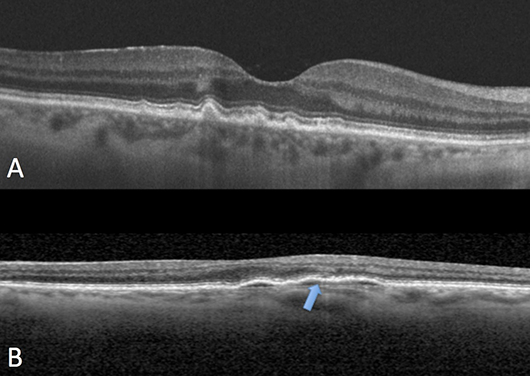

FIGURE 3. A: Multiple drusen. B: This is a low-lying, flat, irregular pigment epithelial detachment. Note the fluid cleft (blue arrow).

|

Drusen are the hallmark of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). They are accumulations of extracellular material that build up between the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and Bruch’s membrane. Patients with drusen should be monitored annually with dilated fundus exam and OCT.

Pigment epithelial detachments (PEDs) are characterized by a separation between the RPE and Bruch's membrane that is occupied by blood, serous fluid, drusenoid material, or fibrovascular tissue. Chronic PEDs are associated with the development of choroidal neovascular membranes so patients should be observed closely.

Patients with a documented history of dry age-related macular degeneration with new-onset metamorphopsia, a clinical exam demonstrating subretinal/intraretinal fluid or hemorrhage, or imaging findings suggestive of a suspicious PED or choroidal neovascular membrane should be referred urgently to a retina specialist for evaluation with fluorescein angiography, optical coherence tomography and/or optical coherence tomography-angiography and initiation of intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy.

The Academy’s YO Info Editorial Board is collaborating with YO leaders from our subspecialty and specialized interest society partners and thanks the Macula Society’s Young Member Representative Dr. Waheed for recruiting Dr. Dukar to collaborate and contribute this article. The Macula Society will hold its 45th Annual Meeting June 8-11, 2022 in Berlin.

|

|

About the authors: Jacob S. Duker, MD, is a first-year vitreoretinal surgery fellow at Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston/Tufts in Boston, Massachusetts. He completed his ophthalmology residency at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami. |

Nadia K. Waheed, MD, is an associate professor in ophthalmology at the Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, research director of the Boston Image Reading Center and the chief medical officer at Gyroscope Therapeutics. Her research interests include novel imaging modalities in the eye, OCT and OCT angiography, clinical trial endpoint development using traditional and machine learning approaches, and the applications of these to non-exudative AMD and diabetic retinopathy. She has published over 100 papers in peer reviewed journals, over 100 abstracts, book chapters and editorials and is the co-author on three books, the "Handbook of Retinal OCT," "Atlas of Retinal OCT" and "OCT Angiography of the Eye."