Author: Aubrey Minshew, Museum Specialist, Truhlsen-Marmor Museum of the Eye®

As Decoding the Eye: Signs & Symbols nears its closing date, I was reflecting on all the eye symbols and mythology we’ve explored over the last year. On the Eye Witness Blog, we’ve decoded stories from ancient Greece, ancient Egypt, and revolutionary America, so I decided it was time to examine one last piece of eye symbolism before the show goes back into the museum vault.

In Decoding the Eye, there are two statues of a serene young woman holding a palm frond and a platter. She is wearing long robes and a calm expression, but when you look closer at the statues, it becomes apparent that her platter holds something startling — two loose eyeballs!

A statue of Saint Lucy from Decoding the Eye — note her platter of eyeballs!

Both statues are representations of Saint Lucy, sometimes spelled Lucia. In the Catholic canon and in other Christian traditions, Saint Lucy is considered the patron saint of the eyes or the blind. Let’s decode why Saint Lucy is holding a platter of eyeballs, how she has appeared in culture over time, and where we can see her in popular culture today.

Another statue of Saint Lucy, with her chalice of eyeballs in one hand and palm frond in the other

The museum’s Saint Lucy statues are representations of a real woman who lived in the third century named Lucia of Syracuse (c283–304 CE). Here, Syracuse refers to a historical city on the Italian island of Sicily, not the American city nor university of the same name. Lucia does not appear extensively in non-religious historical texts, but it seems likely that she was a Christian martyr during the Diocletian Persecution (c303–313 CE), the last major Roman campaign against Christians before Christianity was officially tolerated by the empire. Her name, Lucia, comes from the Latin root lux, meaning light.

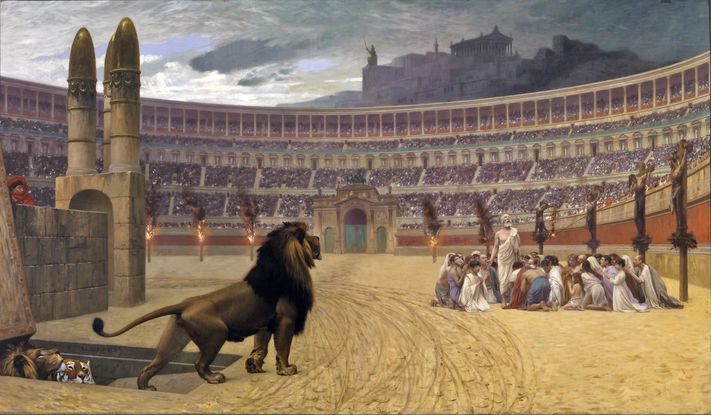

A 19th century inaccurate reimagining of the Diocletian Persecution, by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904)

Most of our information about Saint Lucy’s life comes from hagiography, or religious biographies of the lives of saints published by the Catholic Church. Often, hagiographic accounts combine popular stories and legends about saints, so we have several unique stories of martyrdom associated with Lucia of Syracuse. Usually, Lucia is portrayed as the daughter of wealthy pagan Romans. She converts to Christianity and chooses a life of chastity and devotion. She is eventually executed for her faith after refusing marriage. Depending on the account, Lucia either has her eyes gouged out by soldiers as punishment for refusing to marry, or she gouges out her own eyes to make herself undesirable for marriage. She is unfortunately executed in all versions of the hagiography, but some editions state that her family finds that she has her eyes miraculously restored to her body when they gather to bury her.

Saint Lucy of Syracuse, by Dominico di Pace Beccafumi, c1521

Based on the gruesome and surprisingly ocular nature of Lucia’s martyrdom, it is easy to see why she has been associated with eyes, vision, and the blind for almost two thousand years. However, popular celebrations of Saint Lucy have generally referenced her name’s association with light and brightness, instead of her execution. Her annual religious holiday, Saint Lucy’s Day, is observed on Dec. 13 and is usually considered a festival of light in the darkness of winter.

Saint Lucy, by Francesco del Cossa, c1473–1474

Saint Lucy’s Day festivities may sound familiar to some of our visitors since we celebrated the holiday in the museum this past December. Our Saint Lucy’s Day celebration was based on the popular observance in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, and in Scandinavian communities in the United States. In the Swedish-speaking world, the feast of Sankta Lucia is celebrated by dressing a young girl in the community as Saint Lucy, with a white gown (representing purity), a red sash (representing martyrdom), and a wreath lined with candles around her head (representing light in the darkest time of year). Sankta Lucia is sometimes accompanied by young boys wearing cone-shaped hats decorated with golden stars (stjärngossar or “star boys”). People often exchange coffee and special gingersnaps (pepparkakor) and sweet saffron buns (lussekatter) with their neighbors.

Celebrating Saint Lucy’s Day in the museum galleries with Swedish treats

Since the historical Saint Lucy is associated with Sicily, Saint Lucy’s Day is also a popular celebration in several Italian cities. There, the day often involves processions of statues and relics associated with Saint Lucy. In Syracuse, Saint Lucy is credited with miraculously bringing ships full of grain to the starving city in the 17th century, so it is customary to abstain from pasta and bread on Dec. 13 and instead eat cuccìa. Sweet versions contain boiled wheat, ricotta, and honey; savory cuccìa is made of boiled wheat and beans.

Celebration of Santa Lucia in Syracuse, Italy; Salvo Cannizzaro, via Wikimedia Commons

We can find references to Saint Lucy in many more places. Numerous geographical locations are named for her, perhaps most famously the island country of Saint Lucia in the Caribbean. The Swedish observation of Saint Lucy’s Day may sound familiar to fans of the American Girl historical doll series that was popular in the 1990s and early 2000s; Kirsten Larson, the Swedish immigrant historical doll, has a Saint Lucy’s Day outfit, complete with a wreath of candles. Also, Renaissance-era paintings of Saint Lucy are often used as a visual metaphor in movies and television for martyrdom and Sicilian identity. Most recently, a painting of Saint Lucy can be found in the second season of the popular HBO series The White Lotus, which is set in a Sicilian resort and features themes of death and martyrdom.

Saint Lucy found in the wild: The island nation (left), the American Girl doll (center), and as a painting behind F. Murray Abraham in “The White Lotus” (right, creator: Fabio Lovino/HBO)

Turns out, examining the small statues with eyeballs on a platter in the museum opens a door to a whole universe of religious history, cultural observance, and pop culture references. As the Decoding the Eye: Signs & Symbols exhibit comes to a close, it feels like we have learned that the world of eye symbolism, belief, and mythology is even broader than we thought.

Decoding the Eye: Signs & Symbols closes on Sunday, May 12, 2024. Learn more about museum hours and planning your visit before the show closes.