By Patrick Chan, MD, Reza Iranmanesh, MD, and Emmett T. Cunningham Jr., MD, PHD, MPH

This article is from April 2011 and may contain outdated material.

Steven Jones* was a 37-year-old graphic designer who noticed occasional intermittent blurry vision in his right eye beginning several months prior to presentation. He assumed that his symptoms were related to eyestrain, and ignored them. The symptoms became more frequent, however, and he made an appointment to be seen in our clinic.

We Get a Look

On examination, we noted that his BCVA was 20/25 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left, there was no afferent pupillary defect and his IOPs were 12 mmHg bilaterally. The anterior segment exam was unremarkable.

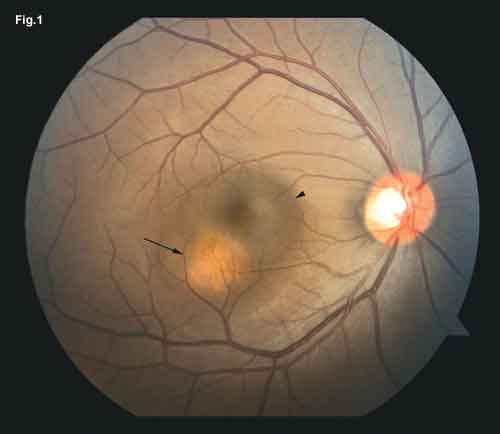

On dilated fundus examination, Mr. Jones had clear media in each eye. We noted serous detachment of the fovea in the right eye, which was contiguous with a well-defined, red-orange, dome-shaped elevation inferotemporally (Fig. 1). There was no abnormal pigmentation associated with the elevation. Examination of the fellow eye was unremarkable.

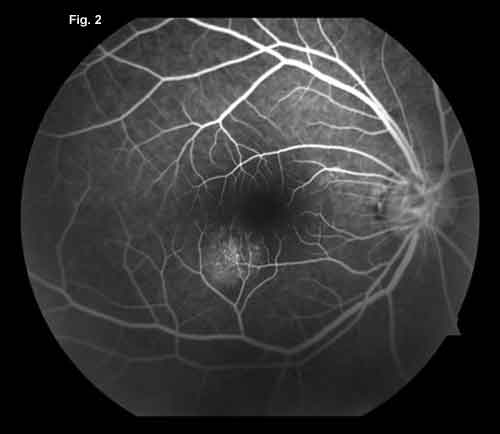

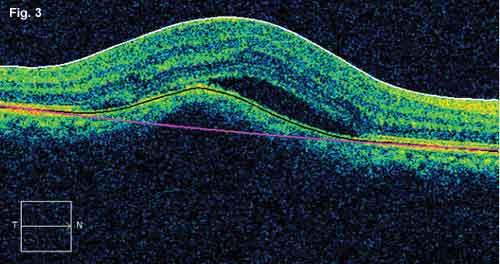

Fluorescein angiography revealed a stippled hyperfluorescence over the elevation with late staining, but without increased intensity (Fig. 2). The lesion was too small to be identified using B-scan ultrasonography, but OCT confirmed it was choroidal with elevation of the overlying RPE and a small area of subretinal fluid (Fig. 3).

Differential Diagnosis

Clinically, the patient had a unilateral choroidal lesion with an overlying serous retinal detachment. The differential diagnosis included a granuloma related to tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, cat-scratch disease or toxocariasis, as well as an amelanotic melanoma, choroidal hemangioma or choroidal metastasis. The fluorescence pattern on angiography suggested that the choroidal lesion was not well-vascularized, which made hemangioma less likely.

Further Testing

Mr. Jones’ workup included serum RPR, FTA-ABS, serum ACE, lysozyme levels and a CBC. He had been tested for HIV a month prior to presentation and was negative. A chest x-ray and PPD skin test were obtained.

Pertinent abnormal laboratory values obtained included an elevated ACE level of 138 U/l (reference range: 9–67 U/l) and elevated lysozyme of 29 µg/ml (reference range: 9–17 µg/ml). Several hours after our patient obtained his chest x-ray, the radiologist called to let us know that the patient had prominent bilateral perihilar lymphadenopathy (Fig. 4). Both the controls and PPD skin tests were nonreactive, suggesting anergy.

Given the clinical appearance of the lesions and testing results, we diagnosed the patient with presumed pulmonary and ocular sarcoidosis. He was started on oral prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day. Subsequent examination revealed resolution of the serous detachment and regression of the choroidal lesion, with confirmation via OCT.

|

|

|

We Get A Look. We saw a well-defined red-orange lesion (arrow) inferotemporal to the macula associated with an adjacent area of subretinal fluid (arrowhead) (Fig. 1). Fluorescein (Fig. 2) revealed that this lesion was nonvascular. OCT (Fig. 3) confirmed that the lesion was choroidal.

|

Pathology and Incidence

First described by Hutchinson in 1869, sarcoidosis is a systemic disease characterized predominantly by pulmonary, cutaneous and ocular symptoms. The disease involves upregulation of helper T-cells resulting in deposition of noncaseating granulomas in the affected tissues. These cells, however, are unable to elicit a full immune response. As a result, up to 80 percent of those with sarcoidosis are anergic to a PPD skin test.

In the United States, the prevalence of sarcoidosis ranges from 10 to 20 per 100,000, with African-Americans 10 times as likely as Caucasians to be affected. Its prevalence worldwide is reported to be as low as 3.7 per 100,000 in Japan and up to 28 per 100,000 in Finland.1

|

|

X-Ray. The radiologist noted enlarged perihilar lymph nodes bilaterally. (Fig 4).

|

Ocular Signs of the Disease

Thirty to 60 percent of patients who have sarcoidosis develop ocular changes, while a smaller percentage of them have symptoms. The most common ocular presentation is acute bilateral anterior uveitis.

Clinical signs of ocular sarcoidosis can include mutton-fat keratic precipitates, iris nodules, vitreous opacities, chorioretinal lesions, periphlebitis and optic disc nodules. Macular edema is a common finding with posterior lesions. Presentation of ocular sarcoidosis with only a solitary choroidal lesion, as with Mr. Jones, is uncommon but has been reported.

Definitive diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis requires histopathology. Alternatively, the International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) has defined a series of clinical findings and laboratory investigations to categorize the likelihood of disease without a tissue diagnosis.2 Based on the IWOS consensus statements, Mr. Jones carried the diagnosis of presumed ocular sarcoidosis, given his clinical presentation and radiographic lymphadenopathy.

Management of an anterior uveitis from sarcoidosis typically requires only topical corticosteroids. A cycloplegic/ mydriatic agent can be added for comfort and to minimize the risk of synechiae formation. Posterior lesions are best treated with systemic or intraocular corticosteroids. Since sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease, it is critical to collaborate with a rheumatologist for complete care of the patient before initiating systemic treatment. Immunomodulators such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil or cyclosporine can be used in those intolerant of, or refractory to, steroids.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Jones, N. and M. Mochizuki. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2010;18:72–79.

2 Herbort, C. P. et al. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2009;17:160–169.

___________________________

Dr. Chan is an ophthalmology resident at Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons. Dr. Iranmanesh is a retina specialist at the Vantage Eye Center in Monterey, Calif. Dr. Cunningham is director of the uveitis service at California Pacific Medical Center and an adjunct clinical professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University.