By Andrea V. Gray, MD

Edited By Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from October 2005 and may contain outdated material.

Kristen Fall* is a 33-year-old woman who was seeing things. For the past month, she had been experiencing transient vision loss lasting only two to three seconds accompanied by colored lights around the edges of her vision. She described the phenomenon as “exactly like when you rub your eyes too hard.” She noticed the symptoms especially when she changed positions, but said it would occasionally occur even when sitting still if she was stressed. There was no accompanying headache, vertigo, weakness, malaise, paresthesia or diplopia.

Her past medical history was significant for gestational diabetes, occasional migraine headaches and seasonal allergies. Her medications included cetirizine (Zyrtec), mometasone (Nasonex), bupropion (Wellbutrin) and low-dose aspirin. She had recently finished a two-month course of minocycline for acne, followed by amoxicillin for sinusitis. She was not overweight.

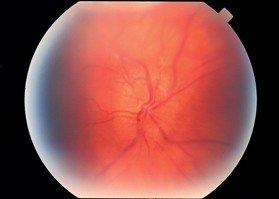

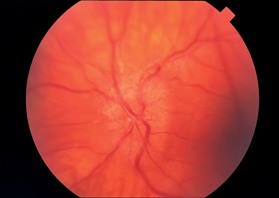

On examination, Ms. Fall had 20/20 vision in each eye, normal intraocular pressures, and normal pupils and motility. Visual fields were full to confrontation in each eye, and color plate testing was unremarkable for either eye. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the anterior segments and external eyes was normal. Dilated funduscopy revealed marked bilateral optic disc edema without hemorrhage. There were no other fundus abnormalities. Her blood pressure was 125/75.

A Humphrey visual field 24-2 test was performed and was within normal limits for both eyes. A CT scan of the patient’s head and orbits was normal. A lumbar puncture revealed an opening pressure of 42 centimeters of water. Cerebrospinal fluid appearance, cell count, glucose and protein were normal.

|

|

What’s Your Diagnosis? Bilateral optic disc edema in a patient presenting with occasional vision loss accompanied by colored lights.

|

Differential Diagnosis

An intracranial mass must be urgently ruled out with cranial imaging in any patient with papilledema. Cranial imaging can also help elucidate the presence of orbital optic nerve tumors, nerve infiltration (e.g., sarcoid, leukemia, metastasis, other inflammatory disease) or dysthyroid ophthalmopathy.

Buried disc drusen or congenitally anomalous discs can give the appearance of papilledema. There are no symptoms associated with these congenital conditions.

Optic neuritis or neuroretinitis can be bilateral and mimic pseudotumor cerebri. Pain on eye movement is often present in these entities while it is usually not a symptom in pseudotumor cerebri. Appropriate laboratory testing of blood or cerebrospinal fluid can be diagnostic of some causes of optic neuritis. Uveitic neuritis is in the differential diagnosis and may be associated with inflammatory signs elsewhere in the eye and may also produce ocular pain and photophobia.

Papilledema caused by hypertensive optic neuropathy is generally accompanied by hemorrhages, cotton-wool spots, narrowed arterioles and dilated veins. Arteriovenous-crossing changes may be present. Measurement of blood pressure in patients with papilledema is helpful in distinguishing hypertensive neuropathy from pseudotumor cerebri.

Type 1 diabetic patients who are young may present with bilateral papillitis, which may in turn be accompanied by diabetic retinopathy. It would not be associated with high opening pressure on lumbar puncture.

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy may be initially unilateral but rapidly becomes bilateral. The typical signs of LHON are disc edema with peripapillary telangiectasis. Pseudotumor cerebri does not usually have telangiectatic vessels. Leber’s optic neuropathy can occur in any patient of any age or sex but is classically found in men in the second to third decades of life.

Pseudotumor cerebri is a diagnosis of exclusion with increased cerebrospinal fluid pressure on lumbar puncture, normal cerebrospinal fluid composition, and a normal head scan. Most patients (80 to 90 percent) present with a headache. The headache will typically be moderate to severe, constant, and may worsen when the patient is prone. Nausea and vomiting may occur. The patient may complain of decreased visual acuity, transient visual obscurations (which are often precipitated by changes in position) or diplopia. The diplopia is caused by unilateral or bilateral cranial nerve VI palsy, which is a nonlocalizing sign within the context of pseudotumor cerebri. Dizziness and tinnitus may also be present.

All Things Considered

A diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri, or idiopathic intracranial hypertension, was made. Ms. Fall was started on acetazolamide (Diamox) 250 mg four times daily for one week, which was then increased to 500 mg four times daily thereafter. Following one week of treatment, the visual symptoms resolved.

Ms. Fall’s presentation was unusual in that she did not have a headache. However, she did complain of transient visual obscurations. She had also recently completed a two-month course of minocycline. This was possibly a contributing factor for her pseudotumor cerebri. Tetracycline, vitamin A (greater than 100,000 units per day), nalidixic acid, oral contraceptives and cyclosporine all have been commonly associated with the disease. Systemic steroid withdrawal or use has also been found to be causative. Obesity and pregnancy are well-associated with pseudotumor cerebri. In fact, most patients are significantly overweight.

Other identifiable etiologic factors include middle-ear disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, radical neck dissection, nonspecific infections and various hormonal abnormalities. The peak incidence is in the third decade of life, and there is a strong female preponderance.

Prognosis and Treatment

The clinical course of pseudotumor cerebri may either be short and self-limited or chronic. Treatment is indicated for patients with severe, intractable headache and/or evidence of progressive decrease in vision or visual field. Because chronic pseudotumor cerebri has the potential to result in progressive and permanent visual acuity or visual field loss, some ophthalmologists advocate treating all patients with the condition, at least with noninvasive means.

Obese patients should be started on a weight-reduction program. Any causative medications should be discontinued. Initial medical therapy, as prescribed for Ms. Fall, generally consists of acetazolamide (Diamox), 250 mg four times daily for one week, which is then increased to 500 mg four times daily, if tolerated. Common side effects of acetazolamide include fatigue, malaise, taste changes, anorexia, nausea/vomiting, paresthesia, tinnitus, diarrhea, polyuria and transient myopia. Furosemide (Lasix) 80 to 120 mg per day may be used in place of acetazolamide. In the pregnant patient, acetazolamide may be used after 20 weeks of gestation.

Serial lumbar punctures can theoretically be used to decrease intracranial pressure, but the accompanying headache or backache discourages the use of this modality.

The use of steroids is controversial. Overweight patients are usually poor candidates for chronic steroid use. While intracranial pressure may decrease with steroids, there is often a rebound effect when the steroids are discontinued.

In cases where medical management fails to halt progression of visual acuity or field loss, a surgical procedure may be indicated. Optic nerve sheath decompression is the procedure of choice. If intractable headache is the primary problem, a shunting procedure (e.g., ventriculoperitoneal or lumboperitoneal shunt) can be effective.

The ophthalmologist must carefully follow all patients with pseudotumor cerebri in order to monitor all parameters of optic nerve function. Visual acuity, color testing and serial formal perimetry are recommended, especially in the initial phases of the disease. The frequency of follow-up visits is determined by the severity and chronicity of the papilledema. In general, patients should be seen initially every four to six weeks and then at longer intervals depending on the response to treatment.

Conclusion

Vision loss can be progressive and permanent if this entity is not recognized.

It is also important to note that pseudotumor cerebri is a diagnosis of exclusion. Any patient with papilledema must be considered to have an intracranial mass until proven otherwise.

______________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

______________________________

Dr. Gray is a comprehensive ophthalmologist in private practice in Roseburg, Ore.