By Christina H. Choe, MD, and Jonathan D. Trobe, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from March 2009 and may contain outdated material.

We were first introduced to Tommy Birmingham,* a 14-year-old high school student, when he came to the emergency room with a right eye that was red and swollen. He said his symptoms had started two weeks earlier, with a dry, nonproductive cough, a sore throat, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. Then, during the course of the previous two days, he developed a headache over the right side of his forehead and neck, occasional diplopia, and redness and swelling over his right eye. This swelling progressed until he was having difficulty opening the eye. Finally, on the day of his ER visit, he experienced an episode of marked disorientation and his parents reported that he had seemed sleepy and a little confused.

Initial Evaluation

The emergency room physicians found that his right eye was grossly proptotic with erythema, and there was edema of the eyelid. The right eye had defective motility. His temperature was 102.3° F, and his white blood cell count was 18,300 WBC/mm3. The presumptive diagnosis was orbital cellulitis. A brain and orbit CT scan was ordered, and the ophthalmology service was consulted.

Our evaluation confirmed significant proptosis; Hertel exophthalmometry measured 22 mm in the right eye and 14 mm in the left. He had reduced right eye abduction (5 percent of normal) and supraduction (20 percent of normal), and he had an estimated 30-prism diopter esotropia with the left eye fixing. The motility of the left eye was normal. Visual acuity in the right eye was 20/40 but improved to 20/20 with pinhole. Intraocular pressure was normal, and pupils constricted normally to direct light stimulus without an afferent pupillary defect. Our anterior and posterior segment exam of the right eye revealed conjunctival chemosis, eyelid erythema and ptosis, but was otherwise unremarkable. Examination of the left eye was within normal limits. Periocular sensation of light touch over his forehead and cheek was equal.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for this case included infection, inflammation (orbital pseudotumor) and malignancy. Given his fever and elevated white blood cell count, we decided to focus on an infectious etiology.

The presence of proptosis and ophthalmoplegia was consistent with orbital cellulitis. However, given the relatively marked abduction deficit and esotropia, we worried that the ocular motility signs reflected impaired function of cranial nerve VI. Furthermore, when an infection limited to the orbit impairs extraocular muscle contraction, the resultant ophthalmoplegia is usually more diffuse. We were therefore concerned that an infection may have spread backward to the cavernous sinus, possibly causing venous thrombosis there.

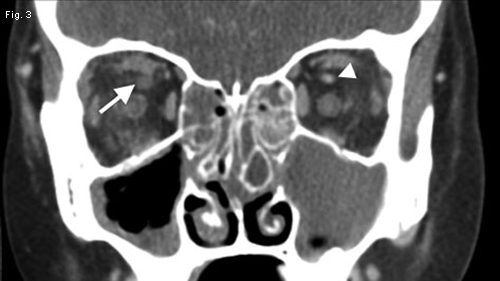

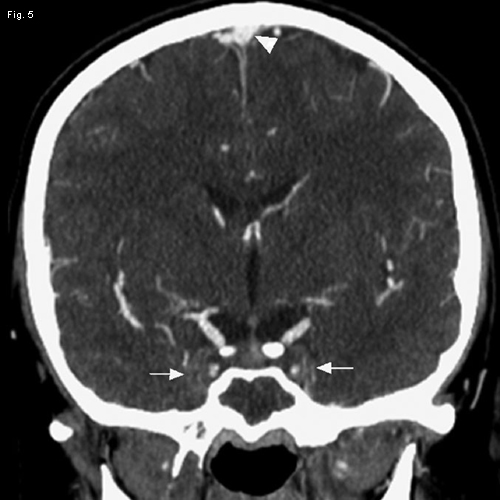

The CT was reviewed with the radiologist and interpreted as showing proptosis, retrobulbar fat stranding and pansinusitis—all consistent with orbital cellulitis (Fig. 1). However, we also discovered a subtle amount of right superior ophthalmic vein dilation (Fig. 2) with decreased contrast uptake (Fig. 3) and a slight fullness to the right cavernous sinus (Fig. 4). This increased our suspicion for septic cavernous sinus thrombosis. A CT venogram was ordered and showed little to no contrast appearing in the cavernous sinus (Fig. 5). Our suspicion was confirmed.

|

|

|

AXIAL VIEW. (1) CT scan of the orbit with contrast demonstrated proptosis and retrobulbar fat stranding. Note the mucosal thickening and fluid in the ipsilateral ethmoidal (single asterisk) and sphenoidal sinuses (double asterisk) consistent with acute inflammation. (2) There is a dilated right superior ophthalmic vein (arrow) compared with the left (arrowhead). CORONAL VIEW AND CT VENOGRAM. (3) The CT scan demonstrated decreased contrast uptake on the right superior ophthalmic vein (arrow) compared with the left (arrowhead). (4) We also noted subtle rounding and fullness of the cavernous sinus on the right (arrow), which contrasted with the flat, slightly concave appearance on the left (arrowhead). (5) The CT venogram demonstrated normal venous filling and contrast enhancement in the superior sagittal sinus (arrowhead). In contrast, the thrombosed cavernous sinus bilaterally failed to show any enhancement (arrows).

|

Discussion

The cavernous sinus is part of the dural venous system, which is valveless and therefore allows both anterograde and retrograde flow. It contains multiple trabeculae that can trap thrombi and bacteria. It sits above the sphenoid sinus and contains many important structures, including the carotid artery and cranial nerves III, IV and VI, as well the first and second divisions of V.

A potentially fatal condition. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis is rare but is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In the pre-antibiotic era, the condition was fatal in nearly 100 percent of cases, and mortality still remains high at 20 to 30 percent.1 In addition, significant morbidity can include blindness, cranial neuropathies and hemiplegia from compromise of the internal carotid artery. There is significant risk of developing meningitis and, due to the intimate relationship of the cavernous sinus with the pituitary gland, Addisonian crisis.

Septic thrombosis of the cavernous sinus can occur by direct extension from the sphenoid sinus, indirect extension from the ethmoid sinus via the superior ophthalmic vein, and posterior extension as a complication of orbital cellulitis. Other potential routes of infection include carbuncles in the medial third of the face and dental infections.

The presentation of septic cavernous sinus thrombosis can be acute and fulminant with bilateral ophthalmoplegia. It also can be subacute and more subtle, as in our case. Headache is the most common initial symptom, and it usually presents as sharp forehead and retro-orbital pain along the distribution of V1 and V2 nerves. Hypoesthesia or hyperesthesia along V1 and V2 is also possible. Owing to the central location of cranial nerve VI in the cavernous sinus, abduction deficit predominates and is also the last to resolve with treatment. Ptosis may be the result of orbital venous congestion, sympathetic paresis or cranial nerve III palsy.

Options for treatment. Owing to the rarity of septic cavernous sinus thrombosis, prospective trials are lacking and there is significant controversy as to optimal treatment, which always includes high-dose intravenous antibiotics. The antibiotics must be continued for more than three weeks due to poor penetration into thrombi.

The causative organisms are commonly gram positive bacteria—such as streptococcal species, like pneumococcus, or staphylococcal species—but anaerobes, gram negative organisms and fungi also have been implicated.1 Thus, the combination of a penicillinase-resistant penicillin and a third or fourth generation cephalosporin is the standard empiric regimen. If there is evidence of sinusitis or dental infection, anaerobic coverage is added.

Anticoagulation is a controversial adjunctive therapy. It should only be initiated after ruling out contraindications, such as intracranial hemorrhage and cerebral infarction. There is significant concern for the increased risk of bleeding complications. However, retrospective observations suggest that anticoagulation is beneficial when started early and is recommended when thrombosis remains unilateral.2,3

Steroids also can be considered, as they have been credited with decreasing the rate of cranial nerve dysfunction. They are especially useful in cases of Addisonian crisis.4 However, steroids should not be initiated until proper antibiotic therapy has been initiated. Finally, surgical drainage of any intracranial abscesses or involved sinuses can be considered.

Be Vigilant

Although septic cavernous sinus thrombosis is rare, its early presentation can masquerade as the more commonly seen orbital cellulitis. Thus, it must always be kept on the differential of infectious causes of proptosis. Subtle signs such as selective ophthalmoplegia and ocular misalignment, which are not typically seen in orbital cellulitis, should not be overlooked. Signs suggestive of meningitis should always be noted in a standard review of symptoms. If neuroimaging is performed, evaluating the superior ophthalmic vein and the cavernous sinus should be routine parts of the review.

Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis is an emergency as it can have devastating complications. It requires an interdisciplinary approach and immediate aggressive therapy, including the consideration of steroids, anticoagulation and anaerobic antibiotic coverage. Overlooking these subtle indicators and initially pursuing the standard empiric therapy for orbital cellulitis could significantly delay the diagnosis with possible detriment to the patient.

Tommy’s Case

Tommy had a lumbar puncture, which demonstrated a slightly elevated white blood cell count (303 WBC/mm3), elevated protein (143 mg/dL) and decreased glucose (42 mg/dL) consistent with bacterial meningitis.

He was admitted and started on intravenous clindamycin, vancomycin and Zosyn (piperacillin and tazobactam). Anticoagulation also was started, and surgical drainage of his sinuses was considered but, owing to clinical improvement, was never pursued. No steroids were used in his treatment.

Tommy remained hospitalized for a week, after which he received outpatient intravenous antibiotics for approximately two months. Anticoagulation was continued for seven months until complete resolution of the cavernous sinus thrombosis.

His ophthalmic findings resolved, with the abduction deficit being the last symptom to resolve.

He suffered no lasting complications.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Ebright, J. R. et al. Arch Intern Med 2001;161(22):2671–2676.

2 Levine, S. R. et al. Neurology 1988;38(4):517–522.

3 Yarington Jr., C. T. Proc R Soc Med 1977;70(7):456–459.

4 Ivey, K. J. and H. Smith. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1968;31:187–189.

___________________________

Dr. Choe is a second-year resident and Dr. Trobe is a professor of ophthalmology and neurology. Both are at the University of Michigan.