This article is from April 2006 and may contain outdated material.

A combination of factors is sparking a renewed interest in Epi-LASIK and other advanced surface ablation procedures—marking a gradual shift away from LASIK for many ophthalmologists across the country.

This shift is occurring because “we can markedly reduce pain through newer medication strategies, thus neutralizing the chief advantage of LASIK,” noted John D. Sheppard, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology, microbiology and cell biology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, and president of Virginia Eye Consultants. “Additionally, some of the new wavefront corrections perform better when applied to the surface because they are not so diluted by the flap anterior to the correction. And there is also the huge safety advantage because of the exceedingly rare anatomical problems of corneal flap procedures. As a result, surface techniques are experiencing a renaissance, with many surgeons moving more toward Epi-LASIK and away from LASIK,” he added.

The Emergence of Epi-LASIK

Epithelial Laser In Situ Keratomileusis (Epi-LASIK) was first introduced by Ioannis Pallikaris, MD, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Crete, Greece. In this procedure, a suction device is placed on the eye to hold it, and an epikeratome is used to separate a sheet of epithelium above the Bowman’s layer and below the basement membrane prior to laser refractive surgery.

Ernest W. Kornmehl, MD, medical director of Kornmehl Laser Eye Associates in Brookline, Mass., chose not to perform LASEK (laser epithelial keratomileusis) because it did not reduce pain or the risk of haze. LASEK involves cutting an ultrathin layer of epithelium, wetting the tissue with diluted alcohol and moving it aside for laser treatment (in contrast to PRK, in which the epithelium is completely removed). In LASEK, this epithelial flap is then replaced to aid in healing.

“Intuitively, covering the cornea with dead epithelial cells did not make sense,” said Dr. Kornmehl. “However, Epi-LASIK intrigued me because although the cells will eventually die, they are living at the time of initial atraumatic separation from the cornea, where you are doing laser treatment, and the release of cytokines is minimized. Pathophysiologically, it makes more sense.”

Flap on, flap off? One of the questions currently surrounding Epi-LASIK is what to do with the epithelial flap that is created.

Since the flap continues to be viable due to the atraumatic removal of the epithelium, should it be placed back in position or not? Dr. Kornmehl currently removes the epithelium once the flap is made. “The major advantage of the epikeratome is its ability to remove the epithelium atraumatically with a smooth edge for 360 degrees, which I feel is more important than having the cells act as a bandage. A randomized trial is the best way to know which is the best flap strategy.” Some small studies currently under way suggest that replacing the epithelial flap actually slows visual rehabilitation.

“This makes sense, again looking at our experience with PRK,” he said. “Patients have faster re-epithelialization when you ablate the cells with a laser rather with the Amoils brush because the laser edge is smooth for 360 degrees.”

Robin F. Beran, MD, FACS, in practice at the Columbus Laser and Cataract Center in Ohio, uses about 60 percent LASIK and 40 percent advanced surface ablation in this practice. He noted that the epithelial flap has also been an issue in connection with the haze rate. “A lot of people say there is less haze with Epi-LASIK as opposed to PRK and LASEK,” he said. “I personally don’t believe there is any difference in haze whether you put the flap down or take the flap off. But to really obtain a definitive answer on the topic, you need to look at patients for at least a year to know your haze rate.”

About that pain. Pain has always been an issue with PRK, Epi-LASIK and other advanced surface ablation procedures.

However, “each surgeon is working out his or her best possible strategies to reduce pain,” noted Dr. Sheppard. He personally uses topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as Acular (Allergan) to reduce pain and inflammation after the Epi-LASIK procedure.

Dr. Kornmehl also does not have any “major issues with pain” with his Epi-LASIK or PRK patients. He has found that applying chilled balanced salt solution immediately after the procedure has been extremely effective. If the surgeon is going to replace the epithelium, then a Weck popsicle should be used instead of chilled BSS to maintain the integrity of the epithelium. He also gives his patients Percocet and prescribes an NSAID to use for two days.

|

|

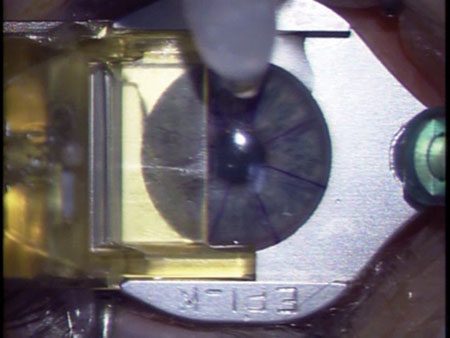

Parting the Layers. The Moria Epi-K is one of several epikeratomes now on the market.

|

Epi-Mechanics

Choosing an epikeratome. Choosing the optimal epikeratome is a matter of personal choice, according to Dr. Sheppard. There are several FDA-approved devices currently on the market, including the Centurion SES EpiEdge epikeratome (Norwood Abbey), the EpiLift System (Advanced Refractive Technologies) and the Epi-K (Moria).

Both Drs. Sheppard and Kornmehl use the Moria Epi-K. Neither has financial interest in this product and both give glowing reports. “I found their product to be beautifully crafted, and they really have a good sense of the issues involved with Epi-LASIK,” noted Dr. Kormehl.

Dr. Sheppard added, “The Moria device is a wonderful part of an integrated line of equipment, including devices designed for lamellar corneal procedures for transplantation. In my opinion, they are very reputable in terms of their devices and service commitment.”

Forgoing the epikeratome? One surgeon who is moving more toward surface ablation techniques in his practice but who has moved away from epikeratomes is Dr. Beran. He started performing PRK in the mid-1990s and then quickly moved to LASIK. “Yet LASIK wasn’t the ultimate answer. Many patients were not good candidates for LASIK because of corneal thickness and dry eye issues, yet it was very difficult to convince them that they should have PRK because of all the negative press that was out,” Dr. Beran said. Seeking an alternative, he contacted Massimo Camellin, MD, after reading his report on LASEK.¹

In 2000, Dr. Beran performed LASEK on 25 eyes in a pilot study and reported his findings at the American College of Eye Surgeons meeting in spring 2001. “The results were as good as PRK at that time, and the main advantage to LASEK was that it did not have the negative baggage of PRK,” Dr. Beran said. “Indeed, I really think that the biggest value of LASEK was that it started getting patients and surgeons to accept surface treatment again when it had fallen out of favor.”

While Dr. Beran welcomed the idea behind Epi-LASIK and began using epikeratomes, “I found that they were extremely uncomfortable to the patient,” he said. “The suction is on so long that it makes the surgery a slower process. In addition, there was inconsistency with obtaining a 10 millimeter epithelial defect with minimal trauma to the edge epithelial cells.”

EtOH to the rescue. So, Dr. Beran has returned to the surface ablation he finds most effective—alcohol—forgoing epikeratomes altogether. In this approach, a dilute solution is used on the eye in a 9-mm holding cup for 20 seconds. This loosens the epithelium so it can be moved to one side or removed altogether in preparation for laser treatment.

The Future of Epi-LASIK

Dr. Beran noted that surgeons are currently struggling to find a way to make visual recovery as quick with surface ablation as it is with LASIK, “But it is unlikely that the epithelial flap is going to behave physiologically in the same way as the LASIK flap. These are two different procedures and surgeons must accept them as such.”

He said that the primary indications for Epi-LASIK (and other advanced surface ablation procedures) are an inadequate corneal thickness for LASIK, dry eyes, occupation (individuals in law enforcement or the military or who are exposed to trauma), suspicious topography or signs of potential for ectasia for LASIK, anatomical abnormalities that preclude using the microkeratome, patient preference and large pupils.

Patient, inform thyself. For Epi-LASIK and other surface ablation procedures to continue gaining popularity, patients must understand not only the procedure itself but how it compares with LASIK and why it may be more appropriate for them. Dr. Beran has created his own informed consent video just for advanced surface ablation techniques.

Dr. Kornmehl agreed that there will be a role for both LASIK and surface ablation and that patient education is vital. He said he will not even set up an appointment with a patient for surface ablation until the patient has had a chance to go home and read up about the procedure. “I want them to do their homework, and then we will have another discussion.”

Dr. Kornmehl added, “There is room for a lot of different procedures in refractive surgery: LASIK, surface ablation, phakic IOLs, multifocal and accommodative lenses. It is an exciting time and procedures are continuing to evolve.”

_________________________________

1 Camellin, M. et al. LASEK: laser epithelial keratomileusis. A new technique for improving healing and decreasing postoperative pain. Presented at the ASCRS meeting, 1999, Los Angeles, Calif.

_________________________________

Drs. Beran, Kornmehl and Sheppard have no related financial interests.

Professional Choices

For years, Academy members have partnered with Professional Choices to launch their careers and find the right personnel for their ophthalmic teams. See what's available in your locality.

Visit www.aao.org/professionalchoices to find a job, fill a job or buy or sell a practice.

|