Download PDF

The risk of acute clinically significant macular edema (ME) after cataract surgery can be cut in half by adding a topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) to the patient’s postoperative regimen of steroid eyedrops, a large retrospective cohort study has concluded.1

Or, if “dropless” prophylaxis is the goal, an intraoperative subconjunctival injection of 2 mg of triamcinolone acetonide alone appears to have effects similar to a commonly used topical corticosteroid, prednisolone acetate, the researchers found.

An unexpected association. “Initially we started off wanting to look at the injection issue, but then a surprising finding was that there was an association [between] adding NSAID to topical steroid and reduction in incidence of macular edema,” said Neal H. Shorstein, MD, study coauthor and cataract surgeon in the Kaiser Permanente health system, Walnut Creek, Calif. Dr. Shorstein also serves as the associate chief of quality for the system’s Diablo Service Area, in Northern California.

The researchers analyzed outcomes of prophylaxis against ME in 16,070 cataract surgeries performed in the service area from 2007 through 2013. Based on their personal preference, the 17 surgeons used 1 of 3 regimens: postop prednisolone eyedrops alone; prednisolone drops plus a topical NSAID (diclofenac sodium, flurbiprofen sodium, or ketorolac tromethamine); or a subconjunctival depot injection of triamcinolone alone at the end of surgery.

Rates of postop ME. The analysis found 118 cases (0.73%) that met the study’s definition for acute clinically significant pseudophakic ME: presentation 5 to 120 days after surgery with a distance visual acuity of 20/40 or worse and with retinal thickening confirmed by optical coherence tomography.

Compared to prophylaxis with topical prednisolone alone, the adjunctive use of a topical NSAID was associated with a 55% lower risk of ME (p < .05; odds ratio [OR], 0.45; 95% CI, 0.210.95), they reported. When eyes with an ocular comorbidity or posterior capsular rupture were excluded, the risk for ME was reduced 65% (p < .05; OR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.13-0.97).

These findings are important because previous studies supporting NSAID prophylaxis generally have suffered from small size, inconsistent criteria for identifying cases and clinical significance, and dependence on ophthalmic industry sponsorship, Dr. Shorstein said.

Unanswered questions. The small number of total cases of ME made it impossible, however, to draw any conclusions about the relative efficacy of the 3 NSAIDs the surgeons used, he noted. “In addition, we still don’t know the effect of NSAID prophylaxis on late visual acuity.”

However, a recently published AAO Ophthalmic Technology Assessment weighed in on that question. In an extensive literature review, it found no conclusive evidence that topical NSAIDs lead to better longterm visual outcomes.2

Dropless data? Because some Kaiser Permanente surgeons inject intracameral antibiotics as the primary prophylaxis for endophthalmitis, forgoing topical antibiotics, Dr. Shorstein said he had been hoping that this study would settle questions about another step toward “dropless” cataract surgery: replacing topical corticosteroid drops with a subconjunctival injection of triamcinolone. However, the number of ME cases the researchers detected in triamcinolone eyes (15) was too small to achieve statistical significance, Dr. Shorstein said.

But he and his coauthors took reassurance from what they didn’t find. “We found no evidence that injected [triamcinolone] depot is less effective than topical administration of [prednisolone] alone. … Injection seems to be safe, as well; we found no diagnoses of globe perforation and no increase in the risk of postoperative (or rebound) iritis or differences in IOP spikes in the late postoperative period,” they wrote.

—Linda Roach

___________________________

1 Shorstein NH et al. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(12):2452-2458.

2 Kim SJ et al. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(11):2159-2168.

___________________________

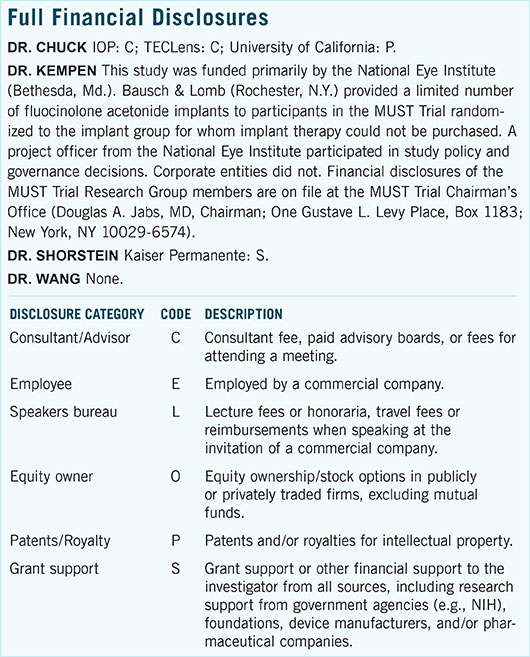

Relevant financial disclosures—Dr. Shorstein: None.

For full disclosures and disclosure key, see below.

More from this month’s News in Review