By Grant W. Su, MD, and Marc R. Sanders, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from April 2006 and may contain outdated material.

Joe Jordan* was in the hospital for hip replacement surgery. During his stay, we saw the 55-year-old as a consult. He told us that, since the age of 30, his complexion had gotten progressively “darker.” Furthermore, over the past decade, he had noticed that darkly pigmented lesions of the conjunctiva had slowly begun to appear in both eyes.

Mr. Jordan had been suffering from chronic painful arthritis of the hips, knees and back. As a result of this, he had bilateral knee and right hip replacement surgeries and a cervical laminectomy. Mr. Jordan denied prior history of ocular problems. His social and family histories were unremarkable.

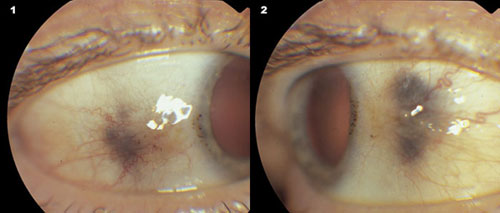

The external exam was significant for a faint bluish-purple discoloration of his forehead, his cheeks, his ear cartilage and the ridge of his nose. His vision was 20/20 in both eyes. When we performed a slit-lamp examination, we saw bilateral blackish pigmentation of the nasal and temporal sclera and bulbar conjunctiva. We also saw drop-shaped globules in the limbic cornea (Fig. 1).

Mr. Jordan’s posterior segment exam was within normal limits.

|

|

What’s Your Diagnosis? Slit-lamp photography reveals dark brown pigment deposits involving the limbic cornea, sclera and conjunctiva.

|

What Turned Up

A review of Mr. Jordan’s medical records revealed that he had been diagnosed with alkaptonuria 12 years earlier. This diagnosis was based on urine studies that revealed elevated levels of homogentisic acid.

It is a rare disorder. Alkaptonuria is a rare disorder of phenylalanine/tyrosine metabolism caused by an autosomal mutation of chromosome 3q, which regulates the metabolism of homogentisic acid oxidase.1 As a result, homogentisic acid accumulates in connective tissues, where it is oxidized into a darkly pigmented melaninlike product. Generally, the incidence is estimated at one in 1 million people. But in Slovakia (formerly part of Czechoslovakia), the incidence is estimated at one in 19,000.2

External signs often appear after the patient turns 30. The external signs of pigment deposition typically begin to appear by the fourth decade of life, usually most apparent at the nasal ala and pinna.

It often involves ocular changes. About 70 percent of alkaptonurics experience ocular changes. These consist of blue-black discoloration of the interpalpebral sclera, just anterior to the insertions of the horizontal rectus muscles. The peripheral cornea also may develop fine, brown “oil droplet” deposits in the Bowman’s layer and the anterior stroma in the interpalpebral region.

There are painful systemic complications. Multiple systemic complications are associated with alkaptonuria. In the skeletal system, a painful degenerative arthropathy results, particularly in the larger joints (knees, shoulders and hips) and vertebral column. In the cardiovascular system, coronary and valvular calcification frequently occurs. In the pulmonary system, dyspnea may arise secondary to restricted chest excursion due to stiffening of cartilage in the chest wall. In the genitourinary system, darkening of urine with exposure to air or reducing agents are common manifestations. In addition, renal and prostatic stones may form.

Differential Diagnosis

There are several possible causes of discoloration. Exogenous ochronosis of the skin, eye and cartilage has been reported to occur secondary to various agents—these include hydroquinones, phenol, picric acid, resorcinol and antimalarials.

Other medications, such as epinephrine-containing eye drops may blacken the conjunctiva, eyelid margins and caruncle.

Ochronosis limited to the eyes has also been reported in patients exposed to quinine dust during its manufacturing.

In addition, the use of topical silver preparations and industrial exposure to organic silver salts or photographic materials may lead to argyrosis. The silver deposition may cause the conjunctiva to have a dark slate-gray appearance, and the cornea may develop peripheral deep stromal and Descemet’s membrane deposits of blue-, gray- or green-colored materials.

Furthermore, systemic conditions such as Addison’s disease and other hormonal changes such as pregnancy may lead to melanin production, which can cause progressive darkening of the skin.

There are several possible causes of lesions. The differential diagnosis for pigmented conjunctival/scleral lesions include conjunctival nevi, primary acquired melanosis (PAM), malignant melanoma and oculodermal melanocytosis (nevus of Ota).

Conjunctival nevi usually develop during the first decade of life and appear as well-circumscribed, brownish lesions often in a juxtalimbal location.

PAM typically appears as patchy, flat, brown pigmentation of the conjunctiva with indistinct edges.

Malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva most often arises in the context of preceding PAM, whereas the remainder of cases occurs in association with a preexisting nevus or de novo. The lesion is an elevated brown mass that most commonly occurs in middle-aged to elderly patients. The lesion may be well vascularized with dilated vessels feeding the tumor.

Oculodermal melanocytosis is a congenital lesion that arises from an arrest in melanocyte migration, resulting in a blue-gray appearance of the sclera. Careful examination reveals that the conjunctiva is free of pigment and is easily mobile over the underlying pigmented sclera.

Management

Given the autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, genetic counseling is indicated in patients with alkaptonuria. Photoprotection may retard the development of solar elastosis and delay ochronosis in the skin. The degenerative joint disease can be treated with exercise and analgesics, but many patients eventually undergo joint replacement surgeries.

Attempts at preventing complications have included limiting tyrosine and phenylalanine in the diet. Since ascorbic acid (vitamin C) inhibits the oxidation of homogentisic acid to the ochronotic pigment, its use has been suggested as a possible means of reducing pigment accumulation in connective tissues. However, the clinical benefits of these treatments have been minimal.

Nitisinone is a promising new agent that has been shown to effectively decrease urinary homogentisic acid levels in patients with alkaptonuria. Nitisinone reduces homogentisic acid production by inhibiting the tyrosine degradation pathway; however, it has the known side effect of elevating plasma tyrosine, which may lead to corneal irritation.3

Clinical trials are now under way to determine the benefits of nitisinone in preventing joint deterioration and providing pain relief.

___________________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________________

1 Chevez Barrios, P. and R. L. Font. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:1060–1063.

2 Srsen, S. et al. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 2002;75:353–359.

3 Suwannarat, P. et al. Metabolism 2005;54: 719–728.

___________________________________

Dr. Su is a fellow in oculoplastic surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin, and Dr. Sanders is at the Diagnostic Eye Clinic in Houston.