9 Tips for Delivering Bad News

Download PDF

Delivering bad news to patients is a highly sensitive challenge that, sooner or later, all physicians must face. Unfortunately, patients aren’t always happy with how that news is broken. “Communication problems on the part of physicians have been cited as the most frequent complaint by patients, while inadequate communication, rather than medical negligence, is the most common cause of health care litigation,”1 said Rosa Braga-Mele, MD, MEd, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Toronto.

How to Deliver Bad News

What steps can you take to communicate better with a patient when you need to deliver unwelcome news? Here are 9 practical techniques that you can use.

Build a relationship. Early on, solidify your relationship with the patient, said Susan H. Day, MD, a pediatric ophthalmologist. By building a rapport based on warmth and trust, you establish a good foundation for any difficult conversations that may be needed later on, said Dr. Day, a former chair of ophthalmology at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco, who is now vice president of medical affairs at ACGME International.

Demonstrate empathy. When delivering bad news, Dr. Braga-Mele puts a premium on the value of empathy—which is derived from the Greek word empatheia, for passion or suffering. “Your most important tools are your own feelings,” said Ivan R. Schwab, MD, professor of ophthalmology and director of the cornea and external disease service at the University of California, Davis. “Bad news comes to us all at some point, and if you deliver news to a patient using your own feelings, you will be a powerful support. Realize that you can never feel the way the recipient feels or truly understand their emotions, but you can comfort and support them as if you were at the threshold of understanding. To start, we should put ourselves in the patient’s position even if we have never received such news. For example—how would we feel if told we would be blind forever?”

Understand the patient’s perspective. “We must constantly be aware of the patient’s, rather than the physician’s, grasp of a specific situation,” said Dr. Day. “As a patient asks basic questions—such as ‘Will things get worse?’—we need to be clear about what we mean by ‘worse,’ rather than assume that the patient’s concept of ‘worse’ is the same as ours.”

Speak in plain language. Use vernacular, conversational language, advised Dr. Day; most patients will not be fluent in the vocabulary of peer-reviewed medical literature. “My sense is that we too often talk in medical terms, rather than in terms that our patients understand,” said Dr. Day.

Schedule enough time for your news and their questions. Dr. Braga-Mele pointed out that even the most attentive physicians don’t always allow sufficient time in their discussions with patients to methodically lay out all aspects of unwelcome developments. Dr. Day added that patients must be given a clear opportunity to ask questions, even if they aren’t the questions that the physician is concerned with. “Physicians may present the information accurately and yet completely miss what might be worrying the patient. One common example occurs when we tell patients their visual acuity will not be great. Their next assumption is often ‘Well, surely you can give me glasses to correct it.’”

Remain available for more interaction. After bad news is delivered, the patient’s ability to absorb subsequent information during that same visit is often lost. As the news sinks in and realities surface, the patient often benefits from further discussions, said Dr. Day.

Optimize the next visit. You can, for example, ask patients if they would like to bring a friend or relative on a follow-up visit, when matters will be addressed in more depth. Beyond helping your patient remember what was said during the visit, this additional person could potentially act as your advocate, helping you get your message across. (But make sure this third party doesn’t hijack the consent process.)

Encourage second opinions. When appropriate, another physician’s assessment is reasonable and could be reassuring.

Allow for hope. Even a glimmer of hope is better than none at all, said Dr. Day.

Don’t Shield Patients From the Facts

The most serious mistakes in delivering bad news may be simply avoiding it altogether or not fully relaying the severity of the situation, said Dr. Braga-Mele. “We naturally feel sorry for the patient in this moment and want to give them hope. Hope is good, of course—but only in the context of remaining truthful and realistic so that, moving forward, the correct care and support systems can be set up.”

|

Being There for the Patient

“Reassure the patient that you will do all you can to help, including helping them plug into community resources,” said Dr. Schwab. “Keep the patient from feeling alone, and assure him or her by discussing any potential rehabilitation that might help. But, above all, patients must know that their physician will accompany them throughout the difficulties. In medicine, our greatest strength is the ability to accompany another person through life’s difficulties. You may not always be able to help, but you can always comfort.”

Know your patient. In the end, “Bad news is still bad news,” said Dr. Day, and it is best handled as a dialogue between the physician and patient. “Such a dialogue requires that the physician know with whom he or she is talking.” This means taking into account such factors as the individual’s capacity to comprehend a big change and any coping mechanisms that the individual is known to have (as evidenced by past events in his or her life). It also entails being sensitive to the patient’s cultural propensities—there may, for instance, be cultural beliefs, fears, or myths that cause a patient to refuse a particular treatment.

___________________________

1 Simpson M et al. Br Med J. 1991;303(6814):1385-1387.

___________________________

Rosa Braga-Mele, MD, is professor of ophthalmology at the University of Toronto and director of professionalism and biomedical ethics and director of cataract surgery at the Kensington Eye Institute in Toronto. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Susan H. Day, MD, is vice president of medical affairs at ACGME International. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Ivan R. Schwab, MD, is professor of ophthalmology and director of the cornea and external disease service at the University of California, Davis. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

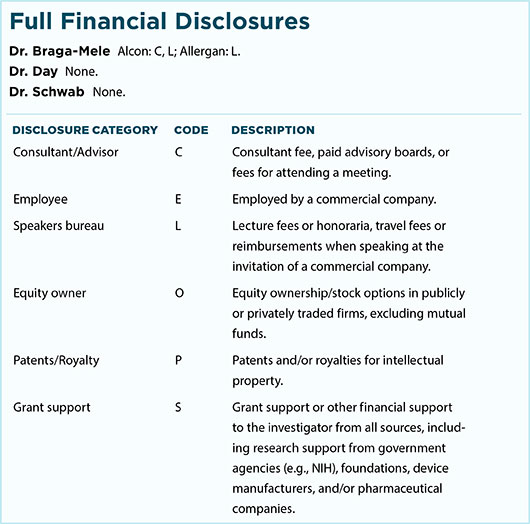

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.

For more articles, click the section links under “YO Guide Content.”