By Kathryn A. Colby, MD, PhD, with Ashley Behrens, MD, Jodhbir S. Mehta, MD, PhD, and Sonal S. Tuli, MD

Download PDF

As the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps across the globe, ophthalmologists have been grappling with questions about ocular manifestations of the disease, protective measures to reduce transmission, and keeping patients informed. Kathryn A. Colby, MD, PhD, of the University of Chicago, hosted an MD Roundtable with Ashley Behrens, MD, of the Wilmer Eye Institute, Jodhbir S. Mehta, MD, PhD, of the Singapore National Eye Centre, and Sonal S. Tuli, MD, of the University of Florida. These cornea experts discuss their firsthand experience with the disease and what they have learned thus far. (For the discussion of ocular manifestations, see “Clinical Experience and Scientific Insights,” below.) This conversation took place on April 22, 2020. See the end of the story to listen to the roundtable or download the audio.

Screening and Eye Care

Dr. Colby: Let’s begin with outpatient treatment since that’s the majority of what we do as ophthalmologists. Which measures are you using to screen patients for SARS-CoV-2 infection in the clinic, and how are you caring for patients who require outpatient procedures, such as laser treatments or injections, during the COVID-19 pandemic?

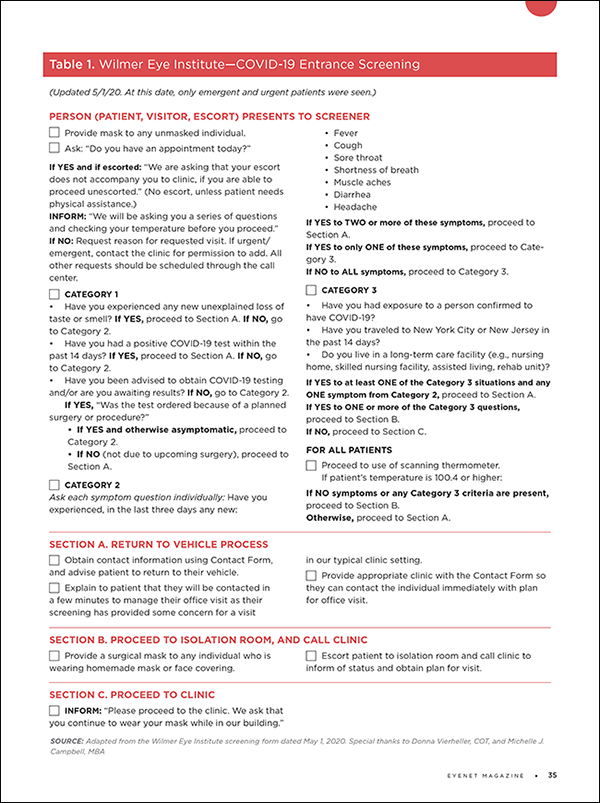

Dr. Behrens: Patients who come to the clinic must first complete a questionnaire to help us determine the potential risk of infection (see Table 1). Patients with confirmed COVID-19 and persons under investigation (PUIs) are not seen in our clinic. They are examined in the emergency department, where we have a slit lamp in a negative-pressure room. For those seen in the clinic, exam rooms are cleaned thoroughly between patients.

Dr. Mehta: We also have patients complete a questionnaire, and they undergo a thermal scan at the entrance of the hospital before arriving at the clinic. If a patient is from a COVID-19 hotspot region, he or she is seen in an isolated area, separate from our main clinic. We also take the temperature of staff members twice a day.

Patients deemed to be at low risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection are seen in the clinic for routine procedures such as retinal injections. We review electronic medical records to determine whether we really need to see the patient at that time, and we ask patients to come to the clinic alone, if possible. We encourage social distancing in the waiting room; we’ve removed half the chairs, and there are markings on the chairs to make sure patients are well separated.

We keep hand sanitizer by every slit lamp and apply it every time a patient is seen. The slit-lamp breath shields are cleaned between patients because even though patients are masked, any droplet or respiratory action against the shield could transmit infection.

Dr. Tuli: We screen every patient—as well as all faculty and staff—before they come into the clinic. We have someone at the door who gives a questionnaire to patients, and we do a temperature scan. We check for sense of smell with scratch-and-sniff cards because loss of this sense is a sign of COVID-19. We’re also considering implementing pulse oximetry because hypoxia is another sign of infection. In general, nonemergency patients are asked to return at a future date.

In the clinic, we have always advised patients and staff to avoid talking at the slit lamp and during injection procedures, and we’re continuing to do that. We’re performing posterior laser treatments as usual. However, we’re not doing any excimer laser treatments because of the plume generated, so we’re avoiding any surface ablation, including phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK).

Dr. Behrens: As a refractive surgeon, I haven’t yet had a case requiring PTK during the pandemic, and of course there are no emergency hyperopic or myopic excimer laser treatments.

For patients with glaucoma who require a Humphrey visual field test, we’re trying to determine the best way to disinfect the machine between patients. The manufacturer recommends a brief cleansing procedure, but even with masking, the bowl can be contaminated by droplets during the test. I’m concerned that infectious virus could still pose a risk to patients.

Dr. Colby: We’ve been considering regular nasal swabbing of our staff, possibly every two weeks or 10 days, as a means of surveillance. We also discourage talking during the exam—when the ophthalmologist and patient are in close proximity—and we’re allotting at least five minutes for cleaning the exam room between patients.

Dr. Colby: How are you providing ophthalmic care to patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19?

Dr. Tuli: For patients given ventilatory assistance who are not conscious, we protect the eyes with lubrication and ensure there’s no lagophthalmos. These are standard measures, not specific to COVID-19.

Dr. Mehta: In the intensive care unit, we also use standard procedures to protect the ocular surface.

|

(Click to download)

|

|

Personal Protective Equipment

Dr. Colby: Describe the personal protective equipment (PPE) that you’re using. Are you triaging PPE according to symptoms?

Dr. Mehta: Patients with COVID-19 are being isolated in the hospital wards. When we see these patients, we wear full PPE, including fit-tested N95 masks. After the experience of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Singapore, these measures have become routine for hospital employees. Staff members who cannot physically wear N95 masks must avoid the isolation units.

Dr. Colby: At our institution, we do annual fit testing for N95 masks to be in compliance, and it has felt like a major undertaking, but now we’re glad to have had the fit test.

Dr. Mehta: For our clinic patients determined to be at low risk of infection, we are not in full PPE. We don’t wear gloves, but we do wear surgical masks while in the exam rooms. The protective gear, including, for example, breath shields on the slit lamp, can be cumbersome for certain procedures, including Goldmann applanation tonometry.

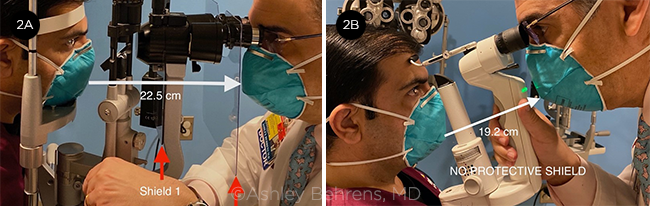

Dr. Behrens: Evidence suggests that asymptomatic patients account for nearly 50% of those infected1 and that almost 50% of transmission can be attributed to asymptomatic or presymptomatic index cases.2 Therefore, our technicians, examiners, and ophthalmologists have been wearing full PPE to see any patient; this means fit-tested N95 masks, gloves, eye protection, and a plastic visor to shield the face. The slit lamp also is equipped with two breath protectors. I tried wearing goggles, but they interfered with exams at the slit lamp. Instead, I wear my regular glasses. Portable slit lamps should be avoided because they require you to be even closer to the patient (see Fig. 2). When we have any difficulty examining a patient with a standard slit lamp, we use a penlight instead.

Dr. Tuli: When we see COVID-19 patients in the hospital for consultations, we wear full PPE, including fit-tested N95 masks, gloves, and gowns. Similarly, we have designated an area of the clinic for PUIs, and we also wear full PPE to examine those individuals.

For patients who do not have symptoms and are at low risk of SARS-CoV- 2 infection, we wear eye protection and surgical masks in the exam rooms. We found low-elevation goggles that work well at the slit lamp, but wearing them for indirect ophthalmoscopy remains a challenge.

Gloves can create a false sense of security. The glove-wearing provider touches the patient and then may touch pens and other items in the room while still wearing the gloves, potentially contaminating those things. For a patient at low risk of infection, it is better to use a cotton-tip applicator or your fingers and then wash your hands.

Some of our providers wear N95 masks for every patient because they’re more concerned, but we generally save the N95s for seeing high-risk patients. Until recently, we didn’t have a sufficient supply of N95 masks to be worn for outpatient care.

Dr. Colby: We set up a room with ultraviolet (UV) light to sterilize our N95 masks, mostly the ones used in the operating room. With UV sterilization, we’re able to use the same mask four times; after sterilization, each mask is returned to the original user.

Dr. Behrens: Our current supply of N95 masks is sufficient to not require sterilizing them. We use them until they are soiled and then change them. Our staff members are universally masked, with N95s for physicians and techs and at least cloth masks for front office staff. If a patient is not already wearing a mask when he or she reaches the entrance of the Wilmer Eye Institute, we provide one.

|

|

NEW CONFIGURATION. At the Wilmer Eye Institute, waiting area of the Comprehensive Eye Care Clinic (1A) before and (1B) after the pandemic started.

|

Telemedicine

Dr. Colby: Are you using telemedicine in any way during the pandemic?

Dr. Tuli: We’re trying to do as much telehealth as possible to limit exposure. This includes phone consultations or video chats, with the patient at home. Some physicians have adopted this more readily than others. We are offering drive-through testing of intraocular pressure (IOP), whereby a technician uses a disposable tip to check IOP. We’re also doing hybrid visits—so, for instance, a patient may undergo optical coherence tomography (OCT) in the clinic and return home. The physician would then call the patient later that day and conduct a telehealth visit. Such hybrid visits help us determine whether a patient needs to come back for an injection and assess the stability of a macular degeneration case. We’re finding that there is a fair bit that we can do by telehealth.

Dr. Behrens: Our glaucoma specialists initially offered drive-through IOP testing, but they stopped because patient response was low. I have done a few telemedicine visits as an anterior-segment ophthalmologist. We use Polycom video conferencing (Poly), which integrates with the Epic system, and it has been difficult to achieve high-quality video for a good examination.

Dr. Mehta: The COVID-19 pandemic has caused us to re-evaluate the amount of time patients spend in the hospital clinic. Retina and glaucoma specialists in Singapore have transitioned to hybrid virtual clinics, like those Dr. Tuli described. For example, patients have a visual field test or imaging in the office, and the results are viewed by a consultant. Patients are contacted by text message to inform them of the results, upcoming appointments, and prescription information. We may also follow up by video conference to explain the findings and schedule the next appointment. We’re finding that these hybrid visits work for about 25% to 30% of our patients; most of them have stable conditions and are presenting for follow-up. An option we’re considering is doing the imaging at a satellite diagnostic center.

We’ve encountered some obstacles with telemedicine. Many of our patients are older and less tech savvy, and we need to make sure they have access to the video conferencing platform. Providing telehealth can be time-intensive, and it requires more imaging than we’d normally do. Another issue has been ensuring that these extra services will be billable.

Dr. Behrens: I’ve been asking some patients to take photos of the eye with their cell phones, and I have a few telehealth imaging tips. I advise patients to use the back camera with flash enabled (not the selfie camera) to produce higher-resolution images. With this, we’ve been able to readily detect conditions such as corneal ulcer and even more subtle presentations, like peripheral keratitis. However, with photos, you can miss a lot.

|

|

AVOID PORTABLE SLIT LAMPS. A standard slit lamp with double breath shield (2A) is preferable to a portable slit lamp (2B) for reasons of social distancing.

|

Precautions With Patients

Dr. Colby: We care for a population that is predominantly older and at risk, and we want to reassure patients that it’s safe to come to the clinic for necessary injections or glaucoma care. How are you letting patients know that it’s safe to come in for exams, and what are you telling them about using contact lenses and eyedrops during the pandemic?

Dr. Tuli: It’s more important than ever to advise patients on good contact lens hygiene, including washing hands before inserting and removing lenses, as well as avoiding touching the eyes while the contacts are in. Disposable lenses should be considered to decrease the risk of contamination associated with reusable lenses. We tell patients to keep using eyedrops and to wash their hands before and after instilling them. This is the advice we’ve given all along, but we’re now emphasizing it more.

We’ve been informing patients by phone on how we’re screening for infection and that we’re deep cleaning the entire clinic twice daily, as well as cleaning exam rooms after each patient’s visit. It’s important to reassure them that the clinic is a safe place to receive ophthalmic care. We’re also planning to provide this information in a letter that is mailed to patients.

Dr. Behrens: I recommend daily-wear contact lenses over reusable ones, and I emphasize that patients should avoid touching the tips of eyedrop bottles. When possible, I use preservative-free medications.

Basically, our clinics are closed; we’re not seeing patients for routine follow-up. We are treating only emergency cases and those that require special care, such as patients who need injections or present with uveitis.

Dr. Mehta: I’ve been recommending that patients avoid wearing contact lenses altogether; I advise wearing glasses for now. My concern is that even with hand washing, patients are likely to contaminate the eye from use of contact lenses. I’m reminding patients to apply eyedrops with clean hands, and we’re strongly recommending that they have eyedrops delivered rather than travel to the pharmacy for them.

To help patients feel confident about their safety in the clinic, we show them the strict protective measures we’re taking. In the lobby of the hospital, there’s a large screen that depicts how we are keeping people from coming to the hospital unnecessarily. Patients see that we are using thermal scanning to check everyone’s temperature. We’re also sharing this information through text messaging.

When we decide that a nonessential appointment should be delayed to mitigate risk, we explain this reasoning, and we emphasize that the doctor has determined that it’s safe to delay the visit. This way, the patient understands that it wasn’t simply an administrative decision to delay an appointment.

Closing Pearls

Dr. Colby: What overarching statements would you like readers to take away from this discussion?

Dr. Mehta: Be aware that conjunctivitis might be an early presenting sign of SARS-CoV-2 infection, even in an otherwise asymptomatic patient (see “Clinical Experience and Scientific Insights,” below). Take extra precautions and obtain a thorough and relevant patient history, including whether the sense of smell or taste has been compromised.

I think the practice of ophthalmology, and of medicine in general, will be changed even after we get through this pandemic; it will be a driver for us to implement more video conferencing and teleophthalmology.

Dr. Behrens: Be exceedingly precautious. Wash your hands thoroughly for 20 seconds before and after seeing a patient and use PPE. Until we have evidence from robust controlled studies showing how SARS-CoV-2 affects the eye, we must practice extreme safety measures to prevent spread to physicians, other health care workers, technicians, and other staff members.

Dr. Tuli: We don’t have definitive evidence about conjunctivitis as a COVID-19 sign or on the likelihood of viral transmission through tears, but practicing strict hand and eye hygiene is always a good idea.

Understandably, our families, staff, and patients are scared and stressed. It’s important for us to explain to them that with appropriate precautions, they can reduce their risk of getting this infection, and that the vast majority of people who become infected will recover. We need to reassure our staff and those under our care that even though the COVID-19 world may be different, we’re resilient and will get through it.

___________________________

Listen to the roundtable below:

Download Audio

___________________________

1 Moriarty LF et al. MMWR. 2020;69(12):347-352.

2 He X et al. Nat Med. 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5.

Clinical Experience and Scientific Insights

COVID-19 and Conjunctivitis

Dr. Colby: The evidence of conjunctivitis in the COVID-19 pandemic is unfolding, with some conflicting reports.1 It seems likely that patients with COVID-19 and conjunctivitis could have infectious virus in their ocular secretions. What’s your current level of concern?

Dr. Behrens: Study findings on this topic have been somewhat contradictory. Available tests to detect the virus, based on reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), are very specific but not that sensitive. We’re probably missing many SARS-CoV-2–positive conjunctival specimens because of false-negative results. Moreover, methodologies have been inconsistent. For example, some investigators collect tear specimens with Schirmer strips and others use swabs, so it’s difficult to compare results across studies.

Dr. Mehta: Conjunctivitis might be an early sign of SARS-CoV-2 infection, but it’s difficult to confirm this. It’s possible that conjunctivitis coincides with detectable viral titer on the ocular surface that is cleared as the disease progresses.

Recently, I saw a patient who presented with conjunctivitis. His travel history was unremarkable, and he seemed to be at low risk for COVID-19, but it turned out that he was positive for SARS-CoV-2. It’s important for providers to be aware that patients with COVID-19 can present with conjunctivitis but otherwise be asymptomatic.

Dr. Tuli: Most respiratory viruses can cause conjunctivitis; with adenovirus or influenza infections, we see conjunctivitis frequently. SARS-CoV-2 infection does not result in conjunctivitis often, but it’s possible that conjunctivitis is a sign of COVID-19. When managing this condition, we need to exercise extreme caution with any procedure that involves touching the eye.

Pathognomonic Signs

Dr. Colby: When a patient presents with conjunctivitis and COVID-19, have you noticed anything about the presentation that might indicate that you’re dealing with SARS-CoV-2 rather than a different virus?

Dr. Mehta: Unfortunately, no. The patients I’ve seen with COVID-19 and conjunctivitis present with what looks like typical viral conjunctivitis. So it’s crucial to obtain a thorough relevant patient history, which includes asking about recent travel and the senses of smell and taste.

We have been treating these cases as we would any standard viral conjunctivitis. We give patients supportive lubricants, advise them to avoid hand-eye contact, and usually see them again approximately two weeks later in a special “clean” area. Because we’re in lockdown, very few patients are coming to the clinic.

We know that the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binds to cellular angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors and depends on TMPRSS2 protease activity for cellular entry. In a single-cell RNA sequencing study, investigators found coexpression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in cells of the respiratory tree and the cornea, including conjunctival cells; however, the receptor density is higher in cells of the nasal cavity and lung than in cells of the conjunctiva.2 Even though the eye may be an entry route for the virus, it does not appear to be a major conduit because of the relatively low receptor density and because the tear film provides innate immunity.

Dr. Tuli: In our center, I haven’t seen any patient with conjunctivitis from COVID-19. An obstacle right now is that patients are presenting with red eyes or conjunctival chemosis, and providers are calling it conjunctivitis. We need to have a standardized description of what we’re referring to as COVID-19–associated conjunctivitis.

Dr. Colby: It seems as if the conjunctivitis is clinically indistinguishable from other viral conjunctivitis; the COVID-19 diagnosis actually is based on other signs and symptoms, such as fever.

Dr. Behrens: I was appointed to the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital in Saudi Arabia when the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) pandemic started, and we saw several patients with systemic MERS but none with conjunctival involvement. However, with the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, we have seen a few cases—mostly in health care workers—of viral conjunctivitis characterized by unilateral redness with a follicular reaction but no tearing or other symptoms. The contralateral eye looks normal, the lymph nodes aren’t enlarged, and there are no symptoms of upper respiratory infection. The conjunctival symptoms last only three or four days. We suspect that these patients have an atypical viral conjunctivitis as a result of SARS-CoV-2 exposure. We submitted a protocol to evaluate these patients further, and it was recently approved by the institutional review board.

Other Ocular Effects

Dr. Colby: Have you seen or heard of any other ocular manifestations in patients with COVID-19?

Dr. Tuli: I haven’t seen any other ocular manifestations clinically. There are ACE2 receptors in the retina, and there’s been some evidence in animal studies of other coronaviruses causing retinitis and other internal uveitis syndromes.3 I’d be interested in knowing if any patients with COVID-19 have undergone pupil dilation to identify retinal manifestations.

Dr. Behrens: We haven’t dilated pupils in patients with COVID-19 because the procedure requires close proximity of doctor and patient, which we are avoiding when possible. However, I agree that that the retina could be another hotspot of coronavirus infection. We are preparing to open a COVID-19 clinic in another location within Johns Hopkins, and we’re hoping to perform OCT so we can evaluate COVID-19’s effects on the back of the eye.

Dr. Mehta: I agree. I haven’t seen anyone present with an ocular symptom other than surface conjunctivitis, but it’s worth exploring. A patient who is immunosuppressed might have a secondary viral retinitis from systemic spread of the virus, but I wouldn’t expect the infection to spread from the ocular surface back to the retina. I also think that any retinal manifestation probably would occur later in the disease course. Recently, there have been reports of uveitis and retinitis, but more details are needed.

Transmissibility and Tears

Dr. Colby: There’s been some suggestion that the virus can be found in tears, and as ophthalmologists, we have exposure to patients’ tears. What’s your level of concern about contact with tears?

Dr. Tuli: There is much concern among our physicians and staff, and there has been some evidence that SARS-CoV-2 might be transmissible through the tear film.4 Realistically, someone is much more likely to get infected if secretions are sprayed through a sneeze or cough as opposed to tear transmission. We make sure to wash our hands after touching a patient and use cotton-tip applicators to lift the eyelids.

Dr. Behrens: I agree. We should be extreme in our measures to prevent contact with tears. I wash my hands and use PPE, including N95 masks, with every patient.

Dr. Mehta: The data are not conclusive to determine a level of concern, in part because of inconsistent timing and methodology of tear sampling and the relatively low sensitivity of RT-PCR to amplify viral nucleic acid from tear samples. For example, topical anesthesia applied during tear sampling may interfere with RT-PCR–based detection of the viral genome.5

I don’t wear gloves when I examine patients, but I use swab sticks rather than touch the eyes with my hands. I apply disinfectant to my hands immediately after seeing each patient. I agree that a cough or sneeze is much more likely than tears to transmit SARS-CoV-2 infection, but practitioners should still be aware of this possibility.

___________________________

1 Zhou Y et al. Ophthalmology. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.04.028.

2 Sungnak W et al. Nat Med. 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6.

3 Seah I, Agrawal R. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28(3):391-395.

4 Xia J et al. J Med Virol. 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25725.

5 Turgut B. Adv Ophthalmol Vis Syst. 2020;10(2):31-34.

|

Dr. Behrens is the KKESH/WEI professor of international ophthalmology and chief of the comprehensive eye care division at the Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute in Baltimore. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Colby is Louis Block Professor and Chair, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science at the University of Chicago. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Mehta is head of the tissue engineering and stem cell group at the Singapore Eye Research Institute and head of the corneal service and senior consultant in the refractive service of the Singapore National Eye Centre. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Tuli is professor and chair of ophthalmology at the University of Florida in Gainesville. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.

Full Financial Disclosures

Dr. Behrens Graybug: P.

Dr. Colby GlaxoSmithKline: C; WL Gore and Associates: C.

Dr. Mehta None.

Dr. Tuli None.

Disclosure Category

|

Code

|

Description

|

| Consultant/Advisor |

C |

Consultant fee, paid advisory boards, or fees for attending a meeting. |

| Employee |

E |

Employed by a commercial company. |

| Speakers bureau |

L |

Lecture fees or honoraria, travel fees or reimbursements when speaking at the invitation of a commercial company. |

| Equity owner |

O |

Equity ownership/stock options in publicly or privately traded firms, excluding mutual funds. |

| Patents/Royalty |

P |

Patents and/or royalties for intellectual property. |

| Grant support |

S |

Grant support or other financial support to the investigator from all sources, including research support from government agencies (e.g., NIH), foundations, device manufacturers, and/or pharmaceutical companies. |

|