Download PDF

Not so long ago, the diagnosis of an advanced-stage or aggressive type of cancer offered limited hope for long-term survival. Yet on Jan. 1, 2019, an estimated 16.9 million U.S. patients with a history of cancer were alive—and this number is expected to increase to more than 22.1 million by Jan. 1, 2030.1

“Long-term cancer survivorship has changed the landscape for ophthalmologists who treat glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and other chronic eye conditions,” said Lauren A. Dalvin, MD, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. “In many instances, metastatic cancer has become a chronic illness. Consequently, it is vital to pay close attention to the ocular health of these patients.”

In Your Practice

At one time, cancer patients didn’t necessarily return to their ophthalmologists after their acute phase of treatment. That’s no longer true. “We must not let those cancer survivors with glaucoma or diabetic retinopathy go by the wayside,” Dr. Dalvin said. “While they may be cancer free, they still must cope with their ocular conditions, and ophthalmologists must be ready to provide individualized care to these patients.”

In addition, the ophthalmologist must be aware of both the ocular adverse effects related to cancer treatments and the possibility of metastasis, said Zélia M. Corrêa, MD, PhD, at the Wilmer Eye Institute in Baltimore.

A brave new world. Although few guidelines exist for managing long-term cancer survivors with chronic ocular conditions, Dr. Corrêa said, a patient who has an eye disease and who also survived a bout with cancer must be managed with the awareness that he or she may live for many more years to come.

“For example, when a patient with an extraocular cancer presents because of conditions such as dry eye, it is important to also evaluate the fundus, not just the immediate problem,” said Dr. Corrêa. In addition, if a patient’s eye disease is progressing, “we need to determine whether this is related to metastases, side effects of chemotherapy or immunotherapy, or an autoimmune condition related to the patient’s cancer, such as carcinoma- or melanoma-associated retinopathy. At this time, the approaches for managing these patients continue to evolve.”

Good histories remain essential. Given these challenges, it is crucial to obtain a thorough health history, said Asim V. Farooq, MD, at the University of Chicago Medical Center.

H. Nida Sen, MD, at the NEI, agreed. “When treating older patients, especially when they develop uveitis without any detectable cause, ask specifically for a list of their cancer drugs.” She also recommends asking whether the patient has experienced any metastases or any infectious or immune side effects from the cancer treatment. “All of these points are relevant in diagnosing and treating long-term cancer survivors.”

Remember older treatments. Although the side effects of newer cancer drugs are in the spotlight, it is important to remember that older chemotherapeutic agents and radiation therapy may also impact a patient’s ocular health, Dr. Farooq said. For instance, patients who are undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy may develop dry eye, punctate epithelial erosions (PEE), or radiation keratopathy, he noted.

Discuss the ramifications of care. “As an anterior segment specialist, I often have discussions with cancer survivors regarding their eye condition in the context of their overall health,” Dr. Farooq said. “For example, if we are discussing a corneal transplant or cataract surgery, we go over a potentially greater risk of infection with an immunocompromised state.”

Beware metastasis. Cancer survivors may present with unexpected ocular issues. Dr. Dalvin noted that while the eye is immunoprivileged, in rare instances cancer can metastasize to the eye when the rest of the body is in remission. “In rare cases, patients in remission can present with what looks to be uveitis but is actually metastatic cancer,” she said. “If there are cells floating around the vitreous, some of these patients warrant a fine needle biopsy to rule out metastatic disease.”

|

|

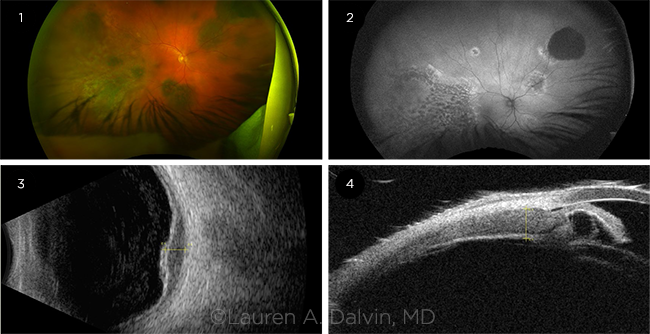

BDUMP. (1) Ultra-widefield pseudocolor fundus photo shows multifocal, deep, pigmented lesions. (2) Autofluorescence reveals a giraffe skin-like pattern. (3) B-scan ultrasonography shows choroidal thickening, which (4) extends into the ciliary body.

|

ICIs: Rewriting the Cancer Script

The increase in cancer survival rates can be attributed in part to the introduction of novel treatment approaches such as the targeted cancer drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

ICIs are contributing to the survival of patients with advanced melanoma as well as to that of patients with other cancers, including cancers of the lung, kidney, colon, and bladder, Dr. Corrêa said. But as she pointed out, when the immune system is activated during cancer treatment, “it is also possible to cause autoimmune side effects on other organs, including the eye. We are seeing an influx of these patients, some with unusual presentations.” (See “Ophthalmic Symptoms Related to Immunotherapy.”)

How ICIs work. ICIs use the body’s immune system to treat cancer, Dr. Dalvin said. Monoclonal antibodies target cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), programmed death protein 1 (PD-1), and programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1). ICIs work at the level of the T cell, blocking inhibitory processes involving CTLA-4 and PD-1. This leads to activation of the T cells, which induces an endogenous autoimmune state designed to fight metastatic cancers.2

Systemic side effects. ICIs can cause adverse effects in the skin, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, and central nervous system as well as the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and musculoskeletal systems, said Dr. Dalvin.

Ocular side effects. Damage to the eyes occurs in approximately 1% of patients on ICIs, typically within weeks to months of starting therapy, Dr. Dalvin said. While myriad ocular adverse effects have been linked to ICIs, the most commonly reported side effects are dry eye, uveitis, and myasthenia gravis with ocular involvement, she noted.

Other ocular adverse events include cranial nerve palsies, inflammatory keratitis, conjunctivitis, cornea graft rejection, and optic neuropathy with visual field loss. And, Dr. Dalvin said, immunotherapy regimens have also been linked to an increase in rare ocular adverse effects, including birdshot-like chorioretinopathy and bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation (BDUMP).

Uveitis Research Helped Lead the Way

During her NIH fellowship from 2002 to 2004, Dr. Sen coauthored one of the first studies linking immunotherapy to uveitis.1

At the time, an mAb was being used in conjunction with tumor vaccines to create a CTLA-4 blockade to improve tumor responses in melanoma. The researchers reported on two patients with stage 4 metastatic melanoma who were vaccinated with glycoprotein 100 (gp100) melanocyte/melanoma differentiation antigen either before or during anti–CTLA-4 mAb therapy.

“We observed that the patients were developing uveitis,” Dr. Sen said. “And this was one of the first reports of autoimmune disease involving the eye in patients treated with anti–CTLA-4 mAb.”

This report has proved to be a harbinger of the ocular adverse effects being seen with ICIs 16 years later. In an effort to better identify these effects, Dr. Sen was part of a retrospective study conducted at three tertiary ophthalmology centers in the United States, looking at electronic medical records of patients undergoing treatment with an ICI.2

“In our study, 11 patients were identified with ocular adverse effects, with anterior uveitis being the most common finding,” Dr. Sen noted. “While the cohort was too small to draw any conclusions regarding specific ocular adverse effects being associated with specific drugs, or drug combinations, we did note that many patients responded well to topical and oral corticosteroids.”

In another study, Dr. Sen and her colleagues identified 14 patients with a new uveitis diagnosis following CTLA-4 and PD-1 checkpoint blockage administration (six anterior uveitis, six panuveitis, one posterior uveitis, and one anterior/intermediate combined).3 “In 11 of the 12 patients, uveitis was diagnosed within six months of starting the ICIs,” Dr. Sen said. “And again, corticosteroid treatment was effective for most of the patients, although two patients experienced permanent vision loss.”

Management of uveitis with local or brief systemic therapy may not require stopping cancer treatment, Dr. Sen said. “Uveitis is manageable in general if treated early. We are not where we were 30 years ago. If we treat early, we can achieve better outcomes. It is important for ophthalmologists to work with oncologists to determine the best overall treatment course.”

Finally, she noted, “If patients present with new-onset uveitis, it is important to take a thorough history to determine if they have been, or are being, treated for cancer. Sometimes patients feel so good that they neglect to bring up their cancer history.”

___________________________

1 Robinson MR et al. J Immunother. 2004;27(6):478-479.

2 Noble CW et al. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. Published online April 23, 2019.

3 Sun MM et al. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;28(2):217-227

|

ICI Side Effects: Odd, Rare, and in Your Office

An unusual case. Dr. Corrêa described the case of a patient with cutaneous melanoma who was undergoing immunotherapy with an ICI and developed uveitis and pigment dispersion. The patient’s hair used to be dark, but the immunotherapy treatment changed the color of her skin and hair. “All of a sudden, this patient had lighter skin, and all the hair on her head and body turned gray,” she said. Moreover, both of the patient’s eyes developed pigment dispersion and intraocular inflammation.

Essentially, Dr. Corrêa said, “The same process [that was affecting her skin and hair] appeared to be occurring in her eyes. Fortunately, the patient responded when the drug was temporarily discontinued and topical steroid therapy was prescribed.”

An increase in BDUMP. ICIs are also being associated with an increase of once-rare ophthalmic conditions. One example is BDUMP, a paraneoplastic intraocular syndrome in which patients present with pigmented uveal lesions, diffuse thickening of the uveal tract, and rapidly progressive cataract. BDUMP is histopathologically unrelated to the primary nonocular tumor.

A decade ago, BDUMP was rarely on anyone’s radar, Dr. Corrêa said. But now, she said, Johns Hopkins is seeing more cases of autoimmune BDUMP in patients treated with immunotherapy. And that experience is reflected in the literature.3

Case example. Dr. Corrêa described a 64-year-old male patient with small cell lung cancer who was referred to her by a local retina specialist. The patient was in remission after being treated with the ICI pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and his vision had decreased from 20/20 to 20/200 in five days. He presented with multifocal patches of melanocytic pigment in the choroid of both eyes, vitreous cells, and macular edema.

“Given his history and clinical presentation, I knew immediately that it was BDUMP,” Dr. Corrêa said. “However, it is important to note that the subtle manifestations of BDUMP can be mistaken for uveitis. And this confusion can delay treatment and increase the possibility of irreparable vision damage.”

Dr. Corrêa was able to coordinate care so the patient was started on plasmapheresis. After a few treatments, the vitreous cleared and his vision improved. He was treated three times a week for three weeks and then twice a week for two months. “Finally, the patient’s vision came around; now, we treat him once a week,” she said.

Dr. Corrêa noted that the patient asked her about his long-term prospects with regard to his vision. “My reply was, ‘This is a good question.’ We probably wouldn’t have even had this conversation 10 years ago, because this patient may not have survived his cancer. Yet here he is: The cancer is under control. Meanwhile, he is experiencing a vision-threatening condition for which we don’t have a definitive treatment.

“It is hard to predict the final outcome,” Dr. Corrêa said. “And we need to be very honest with patients. While there have been significant advances in oncology, we do not yet know the impact in terms of ocular outcomes. We rarely had to manage long-term survivors of nonocular cancers.”

|

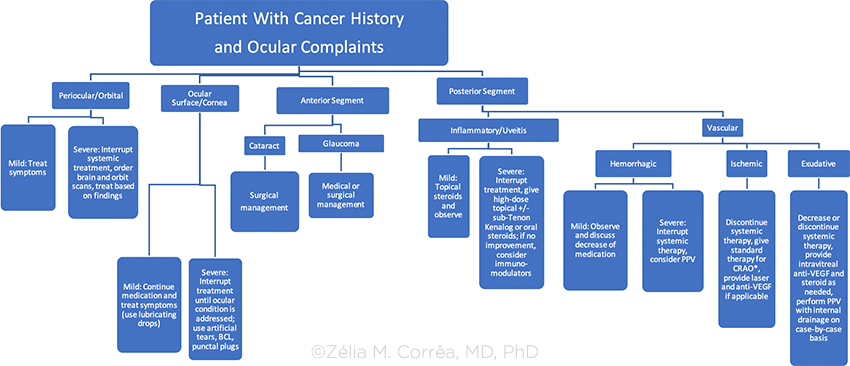

(Click to enlarge)

|

|

|

BCL = bandage contract lens; CRAO = central retinal artery occlusion; PPV = pars plana vitrectomy; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor

*There are a number of therapies for CRAO that include carbogen inhalation, acetazolamide infusion, ocular massage and paracentesis, as well as various vasodilators such as intravenous glyceryl trinitrate. None of these “standard agents” has been shown to alter the natural history of disease definitively. There has been recent interest shown in the use of thrombolytic therapy, delivered either intravenously or intra-arterially by direct catheterization of the ophthalmic artery.

|

ADCs: Another Drug Class to Watch For

In addition to ICIs, ophthalmologists should be aware of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs).

How ADCs work. These drugs involve chemically linking a monoclonal antibody (mAb) to highly potent cytotoxic agents. The mAb binds to cancer cells, and the linked drug enters these cells and kills them, ideally without harming normal cells.

“More than 600 clinical trials with ADCs have been completed or are underway around the world,” Dr. Farooq said. “A number of patients who have failed multiple lines of chemotherapy have been treated successfully with an ADC.”

Systemic side effects. Side effects of ADCs include peripheral sensory neuropathy, nausea, fatigue, and neutropenia.

Ocular side effects. Thus far, it appears that ADCs can cause microcyst-like changes within the corneal epithelium, which can be a cause of decreased vision or refractive shift, said Dr. Farooq.

Case example. Dr. Farooq cited the case of a patient in his 40s with peritoneal mesothelioma who was being managed with an ADC. The patient developed microcyst-like changes within the corneal epithelium bilaterally. “Due to the refractive changes associated with these lesions, he did well initially with bandage contact lenses and preservative-free artificial tears,” Dr. Farooq said. “The contact lenses likely reduced the refractive effect of mild epithelial curvature changes, and he was happy with his vision.”

However, the patient subsequently developed dense posterior subcapsular cataracts in both eyes, likely due to a history of steroid exposure as part of his treatment regimen. He underwent uneventful cataract surgery in both eyes. At present, because of disease relapse, the patient is no longer being treated with an ADC, and the corneal lesions are no longer evident, Dr. Farooq said.

For Further Reading

Suggestions from Drs. Skondra and Corrêa:

Consensus recommendations. Dr. Skondra served on the Toxicity Management Working Group. The group, which was established by the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer, developed guidelines on managing adverse events that develop following therapy with ICIs.1

Grading severity. Dr. Corrêa recommends becoming familiar with the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events reporting system.2 This includes grading tables for the severity of several eye disorders related to cancer treatment. Routine use of the system can improve communication between ophthalmologists and oncologists—which ultimately benefits patient care, she said.

___________________________

1 Golas L, Skondra D. Ocular toxicities caused by immune dysregulation. In: Ernstoff MS et al, eds. SITC’s Guide to Managing Immunotherapy Toxicity. Springer: 2019:201-210.

2 https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/

CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2020.

|

Urgent Call for Collaboration

As ocular side effects of cancer treatment do not occur in a vacuum, the treating ophthalmologist must be in close communication with the patient’s medical oncologist, Dr. Dalvin pointed out.

“When making treatment recommendations, and especially when considering taking the patient to the operating room, it is important to communicate with the oncologist to ensure that it is safe to proceed” as well as to address such systemic issues as platelet count and chemotherapy infusion scheduling, Dr. Farooq said. “It is also important to discuss with the oncologist any ocular side effects to determine treatment or mitigation strategies. In some cases, these side effects may preclude the patient’s ability to stay in a clinical trial.”

What to tell other physicians. It’s also essential to update oncologists and other physicians on ocular issues related to immunotherapy. Dimitra Skondra, MD, PhD, at the University of Chicago Medical Center, is part of a team of specialists who, in a coordinated manner, manage these complex cancer patients. She routinely alerts her colleagues outside of ophthalmology to the links between cancer therapy and ocular side effects.

“It is important for oncologists to know the signs of a potentially blinding condition in patients who are undergoing, or have undergone, immune therapy with checkpoint inhibitors,” Dr. Skondra said. “For example, patients who present with red, painful, dry or irritated eyes, or a visual disturbance, should be referred to an ophthalmologist.”

She added that rapid referral is vital because some symptoms may be difficult to differentiate. “Sometimes grade 2 or 3 severity with ocular adverse events may only present with asymptomatic or mild changes in vision, but these need to be referred promptly.”

Dr. Skondra also warned that oncologists should avoid starting systemic or topical treatment with corticosteroids before conducting an eye exam (unless systemic steroids are indicated for a concurrent, nonophthalmic issue), since the drugs may worsen ocular conditions that are due to infection or mask accurate diagnosis and severity grading during an ophthalmology exam. She added that urgent referral is definitely warranted with grade 3 or 4 ocular adverse events. (For grading information, see “For Further Reading.”)

What to tell patients. Patients undergoing treatment with an ICI should also be told to look for such symptoms as new-onset blurred vision, floaters, flashing lights, changes in color vision, eye redness, photophobia or light sensitivity, visual distortion and visual field changes, scotomas, tender eyes or pain on eye movement, eyelid swelling or proptosis, or double vision.4

“Timely referral to an ophthalmologist is crucial for these patients, which is why it is important for ophthalmologists to have direct open communication with oncologists,” Dr. Skondra said. She added, “And all of us should be aware that these patients are living longer and that symptoms can appear during the maintenance phase of their illness—even five years after therapy has concluded and the patient is in remission. It is a paradigm shift, and one that we all need to pay attention to.”

Ophthalmic Symptoms Related to Immunotherapy

| Adverse Event |

Medication |

Recommendation |

| Amaurosis |

Vemurafenib |

Perform urgent assessment. Withhold drug. |

| Blepharitis |

Afatinib, Erlotinib, Gefitinib |

Perform baseline assessment and management for those known to have blepharitis. If blepharitis progresses, consider ophthalmic antibiotic. |

| Blurred Vision |

Ceritinib, Crizotinib, Dasatinib, Gefitinib, Ibrutinib, Imatinib, Nilotinib, Rituximab, Trametinib, Vemurafenib |

Management depends on severity. At present, certain drugs (Crizotinib, Imatinib, Trametinib) are known to have sight-threatening adverse outcomes. |

| Cataract |

Ibrutinib, Ipilimumab |

Continue systemic treatment; consider cataract surgery. |

| Central Serous Chorioretinopathy |

Trametinib |

Discontinue drug until assessment. Consider modifying dosage or discontinuing drug, depending on findings. |

| Conjunctivitis |

Afatinib, Cetuximab, Dasatinib, Erlotinib, Gefitinib, Imatinib, Panitimumab, Rituximab, Vemurafenib |

Continue systemic treatment. Consider monitoring monthly to address symptoms. |

| Corneal Abrasion |

Erlotinib, Gefitinib |

Withhold drug until resolution of corneal abrasion. Ocular lubrication, BCL, and patching may be indicated. |

| Corneal Melt/Perforation |

Erlotinib |

Withhold drug or modify drug dosage until assessment and management of corneal melt/perforation is performed. |

| Corneal Opacities |

Vandetanib |

Perform baseline assessment prior to initiation of medication. Stop medication and reassess if patient develops any ocular symptoms. Topical steroids and close monitoring are recommended. |

| Corneal Ulceration |

Erlotinib, Gefitinib |

Manage immediately. Withhold drug until improvement is noted. Topical antibiotic recommended. |

| Diabetic Macular Edema (Cystoid) |

Dabrafenib, Vemurafenib |

Immediately evaluate fundus and perform OCT. Stop drug: If edema resolves, consider resuming drug at a lower dosage or changing to another drug. If edema does not resolve, give intravitreal anti-VEGF injections. |

| Dry Eye/Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca |

Erlotinib, Gefitinib, Trametinib |

Use artificial tears. Consider continuing drug or modifying dosage based on patient symptoms. If severe, withhold medication until management is performed. |

| Epiphora |

Panitimumab |

Continue medical regimen. Evaluate tear film and lacrimal drainage; manage symptoms. |

| Episcleritis |

Ipilimumab |

Consider withholding drug until ophthalmology management is performed. |

| Glaucoma |

Rituximab |

Immediate assessment if there are signs and symptoms of acute angle-closure glaucoma (severe ocular pain, redness, and blurred vision). |

| Iridocyclitis/Iritis |

Ipilimumab, Vemurafenib |

Consider withholding medication until ophthalmology evaluation/treatment is performed. |

| Ocular Ischemia |

Gefitinib |

If severe, consider withholding medication until evaluation and management are performed. |

| Ocular Pain |

Rituximab, Vemurafenib |

Consider withholding drug until evaluation and management are performed. |

| Periorbital Edema |

Imatinib, Nilotinib |

If mild, continue drug and provide supportive therapy. If severe, withhold medication, perform orbital imaging, and provide local management. |

| Pseudoproptosis |

Ipilimumab |

Consider dosage changes or withholding medication until assessment and orbital imaging are performed. |

| Retinal Artery Occlusion |

Vemurafenib |

Withhold medication and provide urgent management if symptoms are acute (≤24 hours). If symptoms are >24 hours, provide appropriate management to prevent complications (such as retinal ischemia). |

| Retinal Pigment Epithelium Detachment |

Trametinib |

Consider modifying dosage or withholding the medication until appropriate management can take place. |

| Retinal Vein Occlusion |

Trametinib |

Withhold medication and provide immediate management if symptoms are acute (≤24 hours). If symptoms are >24 hours, manage accordingly. |

| Subconjunctival Hemorrhage |

Imatinib, Nilotinib |

Continue drug. Provide routine evaluation and supportive care as needed. |

| Superficial Punctate Keratopathy |

Gefitinib |

If mild, provide artificial tears and continue medication. If severe, use BCL and consider withholding medication until improvement occurs. |

| Trichomegaly |

Afatinib, Erlotinib, Gefit |

Trim lashes as needed. Manage if symptoms affect vision or if there is direct lash/corneal touch. |

| Uveitis |

Dabrafenib, Ipilimumab, Vemurafenib |

If mild, consider topical steroids, withholding medication, or modifying dosage. If severe, discontinue medication and perform ophthalmic/systemic management. |

| Vitreous Hemorrhage |

Gefitinib |

If severe, perform ultrasound assessment and PPV if nonclearing. Consider withholding medication until assessment. |

| BCL = bandage contact lens; OCT = optical coherence tomography; PPV = pars plana vitrectomy; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor. SOURCE: Zélia M. Corrêa, MD, PhD |

___________________________

1 Miller KD et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363-385.

2 Dalvin LA et al. Retina. 2018;38(6):1063-1078.

3 Klemp K et al. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95(5):439-445.

4 Puzanov I et al. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5(1):95.

Meet the Experts

Zélia M. Corrêa, MD, PhD Director of ocular oncology and echography services at the Wilmer Eye Institute, professor of oncology and ophthalmology, and the Tom Clancy Endowed Professor at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Lauren A. Dalvin, MD Ocular oncologist and assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Asim V. Farooq, MD Cornea specialist and assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Chicago Medical Center. Relevant financial disclosures: GlaxoSmithKline: C.

H. Nida Sen, MD Lasker Clinical Research Scholar, a clinical investigator, and director of the Uveitis Clinic and Uveitis and Ocular Immunology Fellowship Program at the NEI. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dimitra Skondra, MD, PhD Vitreoretinal specialist, associate professor of ophthalmology and visual science, and director of the J. Terry Ernest Ocular Imaging Center at the University of Chicago Medical Center. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Full Financial Disclosures

Dr. Corrêa Castle Biosciences: C; Immunocore: C.

Dr. Dalvin None.

Dr. Farooq GlaxoSmithKline: C.

Dr. Sen None.

Dr. Skondra Allergan: C.

Disclosure Category

|

Code

|

Description

|

| Consultant/Advisor |

C |

Consultant fee, paid advisory boards, or fees for attending a meeting. |

| Employee |

E |

Employed by a commercial company. |

| Speakers bureau |

L |

Lecture fees or honoraria, travel fees or reimbursements when speaking at the invitation of a commercial company. |

| Equity owner |

O |

Equity ownership/stock options in publicly or privately traded firms, excluding mutual funds. |

| Patents/Royalty |

P |

Patents and/or royalties for intellectual property. |

| Grant support |

S |

Grant support or other financial support to the investigator from all sources, including research support from government agencies (e.g., NIH), foundations, device manufacturers, and/or pharmaceutical companies. |

|