By George M. Watson, MD, and Ivan R. Schwab, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from November/December 2008 and may contain outdated material.

Ami Chester* was a busy, 22-year-old Caucasian woman who had recently relocated to start a new job. One evening, she experienced a sudden onset of constant pressurelike pain in her right eye, associated with redness, blurred vision and photophobia. She tolerated this for a week before visiting her ophthalmologist. He diagnosed Ms. Chester with a first-time episode of iritis and treated her with a topical corticosteroid.

Two weeks of therapy brought relief of eye redness but no improvement in her remaining symptoms. Concerned about the continued pain, blurriness and photophobia, Ms. Chester went back to her treating physician. He questioned her on history of fever, systemic illness, recent travel or camping, insect bites, low back pain, skin rashes, mouth sores, bowel abnormalities and animal exposure. The only positives included an occasional mouth sore and having a pet cat, which she had given away four months earlier.

The physician ordered a series of blood tests.

Within a week, Ms. Chester was informed that she was positive for antibodies to herpes simplex virus. The physician initiated oral acyclovir along with the topical corticosteroid.

After another two weeks, Ms. Chester discovered something that prompted her to reconsider her treatment: She was four weeks pregnant. For fear of harming her unborn child, she discontinued the medications.

At this point, she was referred to our uveitis clinic.

|

|

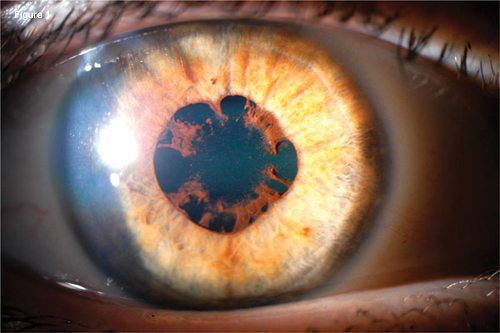

Anterior Segment of the Right Eye. We observed that the patient had white and quiet conjunctiva and a blunted light reflex due to trace corneal edema. Note the hazy appearance of aqueous from cell and flare reaction as well as posterior synechiae and pigment deposits on the anterior lens surface (Fig. 1).

|

We Get a Look

When we evaluated Ms. Chester, she reported no further improvement in her presenting symptoms. What’s more, she told us that she had developed a new floater in her right eye.

Ms. Chester’s vision was 20/30 in the right eye with eccentric gaze, no relative afferent pupillary defect and full visual fields.

Her IOP and motility examination were both normal. Her periorbital tissues and eyelids were unremarkable and her conjunctiva, episclera and sclera were white and quiet. Corneal examination revealed trace stromal edema and fine diffuse pigmented keratic precipitates, and she was noted to have 1+ inflammatory cellular reaction without flare.

Her iris revealed 360 degrees of incomplete posterior synechiae formation with pigment deposits on the anterior lens (Fig. 1).

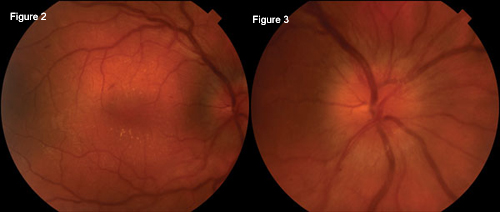

We noted that her lens was clear, but she had 2+ inflammatory cells throughout her vitreous, along with 2+ optic nerve edema with hyperemia. Her macula demonstrated inner layer lipid exudates in star formation along with scattered flame-shaped hemorrhages (Figs. 2 and 3).

Ms. Chester’s left eye was normal.

|

|

Posterior Segment of the Right Eye. In the right posterior segment, we noted diffuse optic nerve edema, retinal nerve fiber layer thickening, inner layer macular exudates in star formation, and scattered flame-shaped hemorrhages (Figs. 2 and 3). Compared with the left posterior segment, which was normal, the right posterior segment had a relatively poor view due to vitreous cells.

|

Differential Diagnosis

To help narrow our differential of acute panuveitis with papillitis and macular star formation, we immediately considered infectious and autoimmune causes.

The initial diagnosis, herpes simplex virus infection, is well known to be a cause of iridocyclitis as well as posterior segment inflammation, such as acute retinal necrosis. Given the high seropositivity in the general population, herpes simplex virus titers are generally not indicated.

While her findings were not typical of herpes pathology, we chose not to dismiss this initial thought, as pregnancy elicits a downregulation of the immune system in order to avoid triggering an immune reaction against foreign proteins.

Higher on the differential of infections were bartonellosis, leptospirosis, Lyme disease, syphilis, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis and numerous others.

Autoimmune causes to be considered include HLA-B27, sarcoidosis and multiple sclerosis.

Serology Workup

To begin our serology workup, we heavily considered bartonellosis and toxoplasmosis, given the history of remote cat exposure.

Lues serology was ordered, although we hoped for negative results given the teratogenic association. Given our patient’s lack of historical or systemic findings pointing to other possibilities, we broadened our initial serology investigation by including Lyme and HLA-B27. Bartonella henselae and B. quintana IgG titers returned weakly positive, 1:64, yet negative for IgM.

On the basis of her clinical presentation and serology data, Ms. Chester was diagnosed with neuroretinitis, secondary to Bartonella henselae, or cat-scratch disease.

Discussion

Pathology. Bartonella henselae is a pleomorphic, gram-negative bacillus that has been described as an intracellular parasite, however, its direct pathologic role is unknown.1 The organism has been associated with numerous ophthalmic pathologies: neuroretinitis or Leber’s idiopathic stellate neuroretinitis, Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome, chorioretinitis, serous macular detachment, optic neuritis and panuveitis.2

Diagnosis. Clinically, neuroretinitis presents classically with unilateral vision loss, papillitis and macular star exudates.

However, patients can develop all or a combination of the following findings: anterior chamber or posterior chamber inflammatory cells and/or flare, peripapillary nerve fiber layer hemorrhages, multifocal yellow-white deep chorioretinal lesions,1 macular edema, serous retinal detachment, cotton-wool spots and dilated retinal vessels.2

Though not typical, involvement can be bilateral. Patients often demonstrate relative afferent pupillary defects and dyschromatopsia, and present with systemic symptoms of fever, malaise and night sweats.1

Positive immunofluorescent antibody has been associated with positive blood cultures for B. henselae.1Further, in a relatively large case series of 18 patients with neuroretinitis, nine of 14 tested patients (64.3 percent) were found to have elevated IgG or IgM antibodies to B. henselae, suggesting current or past infection.2

Such testing is reported to have 88 percent sensitivity and 96 percent specificity, with only 3 percent incidence in the general population and 9 percent with idiopathic uveitis. With such low titers in the general population, positive titers of even past infection provide sufficient rationale to support the diagnosis.2

Treatment. There is little consensus regarding treatment. With such low prevalence, randomized controlled treatment trials for B. henselae–associated pathology including neuroretinitis have not, to our knowledge, been conducted.

Prior to association with B. henselae, the natural history of neuroretinitis suggests spontaneous recovery over several months. However, in hopes of preventing visual disability and prolonged febrile illness, the use of antibiotics has been accepted as standard care.1

Tetracyclines, macrolides, quinolones and rifampin have all shown antimicrobial activity against B. henselae.

A relatively large case series of seven patients with B. henselae–associated neuroretinitis investigated the outcome of treatment at time of diagnosis with doxycycline, 100 mg twice a day, in addition to rifampin, 300 mg two or three times a day for four to six weeks. Constitutional symptoms and fever improved in three or four days and anterior chamber and vitreous cells, papillitis and macular edema regressed within one week. Further, blood cultures at four weeks revealed clearance of bacteremia.1

However, a separate large case series of 18 patients found no clear difference in degree of or time to recovery among various nonstandard antibiotic therapies.2

Prognosis. Nearly all patients in the two relatively large case series of neuroretinitis recovered vision to 20/40 or better.1,2 One- to two-year follow-up in seven patients found two eyes with residual optic disc pallor, relative afferent pupillary defects, retinal pigmentary changes and mildly decreased visual acuity. Electrophysiologic tests comparing affected and fellow unaffected eyes revealed persistent subnormal contrast sensitivity, color vision and visually evoked potentials, yet normal electroretinograms, suggesting a mild resultant optic neuropathy.1

Ms. Chester’s case reminds us of the need for well-designed laboratory and animal studies that can help guide treatment in such challenging dilemmas. However, with Bartonella-associated neuroretinitis, as with any disease of low prevalence, it is difficult to raise funding and recruit patients for prospective studies large enough to investigate the natural history and effective treatment of the condition.

|

|

|

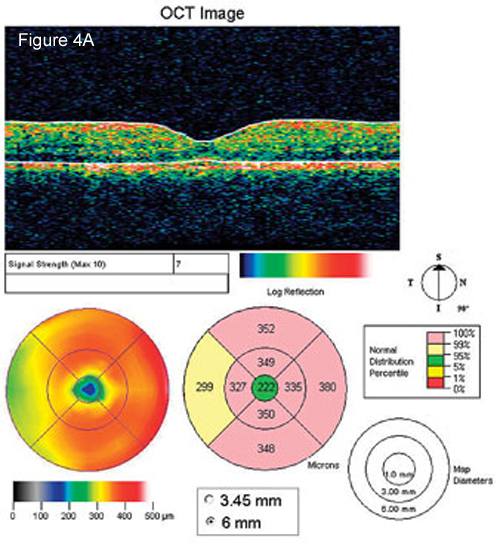

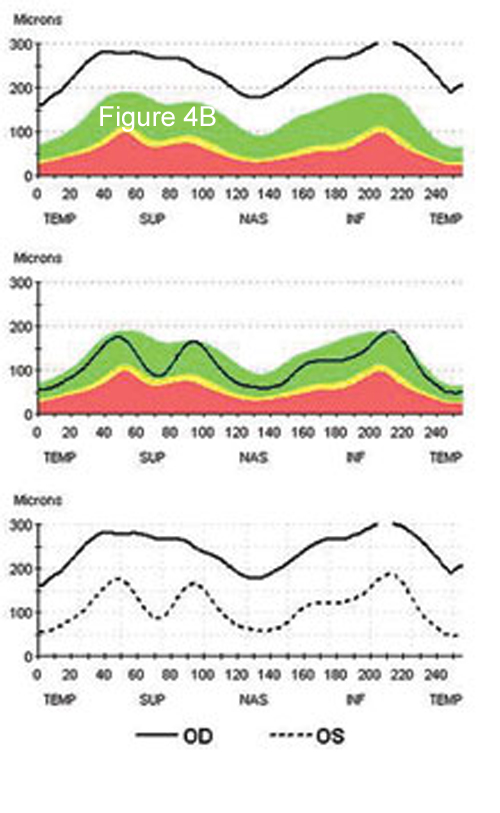

OCT. We observed that the patient had diffuse retinal nerve fiber layer thickening in her right eye compared with the normal left eye. Note the diffuse para- and perimacular thickening corresponding to clinical macular star (Figs. 4A and 4B).

|

Ms. Chester’s Case

Being in her first trimester, Ms. Chester posed a challenging therapeutic dilemma.

While no literature can be found regarding B. henselae–associated neuroretinitis in pregnancy, reports of other systemic diseases caused by Bartonella species, including henselae, during pregnancy suggests transplacental infection and increased risk of maternal and neonatal mortality.3

One must weigh the risks and benefits of observing vs. treating not only for the patient but also for the potential teratogenic consequences of any decision.

After consultation with her obstetrician, it was decided that she begin oral azithromycin (500 mg, twice a day for one to two weeks depending on clinical response), as well as prednisolone 1 percent (one drop to right eye, four times daily).

Note that this treatment regimen consisted of drugs in pharmaceutical pregnancy categories B and C. Drugs fall within category B if a risk to the fetus has been demonstrated in animal studies but not in human studies. Category B also applies if animal studies of a drug haven’t demonstrated a fetal risk but no adequate human studies have been conducted. Category C indicates that animal studies indicate a risk to the fetus but no adequate human studies have been conducted.

She presented one week later with 20/20 vision in the right eye, rare anterior chamber cell, no flare and a resolving macular star. The degree of papillitis, however, had not improved and optical coherence topography was ordered for future objective comparison (Figs. 4A and 4B).

Ms. Chester completed a full 10-day course of therapy, and her papillitis completely resolved at one month. Subjectively, she reports that the photophobia and floaters have resolved. She believes the right eye vision is not as sharp as the left, though she tests 20/20 in both eyes. She is still being actively followed during the course of her pregnancy.