By Gabrielle Weiner, Contributing Writer, interviewing Valérie Biousse, MD, Prem S. Subramanian, MD, PhD, and Jonathan D. Trobe, MD

Download PDF

Many ophthalmologists consider retinal TIA (transient ischemic attack), or amaurosis fugax, to be a relatively benign condition that carries a low risk of stroke. But transient monocular vision loss (TMVL) of vascular origin has the same mechanisms and causes as cerebral ischemia—and, unfortunately, the same systemic implications.

Moreover, new evidence is challenging the old teaching that retinal TIAs have a better prognosis than hemispheric/cerebral TIAs, highlighting the need to treat the conditions with equal urgency.1,2

In other words, retinal TIAs need to be taken as seriously as cerebral TIAs are, as they carry a high risk of stroke and cardiac events—and their occurrence calls for immediate evaluation and, when required, urgent referral.

What Is a TIA?

Previously, the definition of TIA was entirely time-based: That is, patients with spontaneous acute visual loss or neurologic deficits were considered to have a TIA if the deficit lasted under 24 hours.

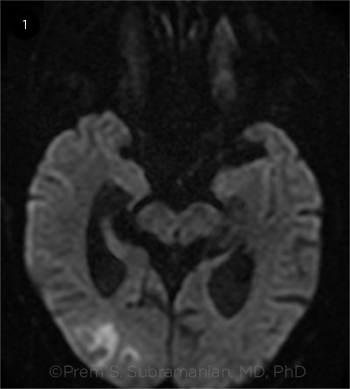

Today, however, the definition of TIA is tissue-based and includes the absence of ischemia on funduscopic examination and on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), which indicates that DWI-MRI needs to be performed. According to the stroke association, a TIA plus a positive DWI-MRI is a stroke (Fig. 1).

|

|

NOT BENIGN. According to the American Stroke Association, a retinal TIA plus positive findings on DWI-MRI equals a stroke.

|

Why Worry?

Data published over the past decade in the neurology and emergency medicine literature have demonstrated the need for a prompt stroke workup in all patients with acute cerebral and ocular ischemia. Unfortunately, many ophthalmologists are unaware of how urgent the disposition should be, said Jonathan D. Trobe, MD, at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Warning sign. Dr. Trobe urged ophthalmologists to recognize that a retinal TIA is a warning sign of possible impending stroke, especially in patients older than 50 years or those who have other conventional risk factors for stroke, such as high blood pressure, smoking, elevated blood lipids, ischemic heart disease, obesity, and family history of premature ischemic heart disease, hypertension, or stroke.

Poor prognosis. Not only is there a clear connection between retinal TIA and stroke, but recent research also demonstrates that retinal arterial ischemia (both transient and fixed) carries almost the same overall poor vascular prognosis as cerebral ischemia.

Don’t delay. To date, the average time from onset of TIA to treatment has tended to be much longer for retinal TIAs than for cerebral TIAs (48.5 vs. 15.2 days in a 1995 study).3 Likewise, a 2012 Canadian study showed that carotid stenosis surgery is often delayed by 1-2 months when the symptom is a retinal TIA.4

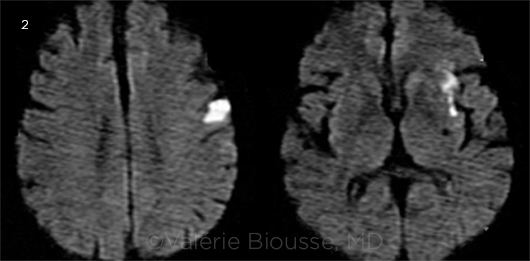

Beware asymptomatic strokes. In a 2012 study, approximately 1 of every 4 patients with acute retinal ischemia had acute brain infarctions on DWI.1 In other words, there was evidence of an asymptomatic stroke. “Although this study was published in a major neurology journal, it has remained largely unnoticed by eye care providers,” said Valérie Biousse, MD, at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

More recent studies in both the stroke and ophthalmic literature have shown remarkably similar results.2,5-7 For instance, a 2014 study reinforced the strong correlation between the presence of abnormalities on DWI-MRI and positive results on the stroke workup for a major cause of stroke (such as a source of emboli), underscoring the usefulness of immediate MRI, even in patients who appear neurologically asymptomatic2 (Fig. 2).

The big picture. “Increased awareness of the dangers of retinal TIAs should change the practice of eye care providers,” said Dr. Biousse. “I am not saying that ophthalmologists should send every patient with TMVL for an MRI. I am saying that they need to take the time to identify the small subgroup of TMVL cases that appear to be vascular and refer those to a stroke center immediately.”

“It may seem like a big leap, but the most recent evidence demonstrates that up to 25%-30% of MRIs on people who have had retinal TIAs will show the same acute changes in the brain on DWI sequences that we see in patients who have had hemispheric TIAs with transient weakness or loss of speech,” said Prem S. Subramanian, MD, PhD, at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora.

He added, “This is the same percentage as hemispheric TIA patients, and we send those patients for an immediate stroke workup without question; it’s standard treatment. We need to do the same for retinal TIAs.”

|

|

ASYMPTOMATIC. Area of asymptomatic acute cerebral ischemia (in white) seen on DWI-MRI obtained 24 hours after an episode of TMVL in the left eye. The patient had no neurologic symptoms and was found to have left internal carotid artery dissection on a magnetic resonance angiogram.

|

Is It a Vascular Event?

When you see patients with TMVL, the greatest challenge will be to identify the small subgroup of patients with TMVL of vascular origin. Because the vision loss is transient, by the time the ophthalmologist sees the patient, most of the time the patient is fine and the eye exam is normal.

Listen to the patient. “The only way to know [whether your patient is at elevated risk] is to spend a lot of time with the patient and to do a very thorough eye exam,” said Dr. Biousse. “Nowadays, ophthalmologists don’t have the time. That’s why having a systematic approach to this symptom is so important.”

Assess symptoms. Transient vascular events tend to last a few minutes but not more than 60-90 minutes (if an event lasted longer, it would likely leave some permanent damage). They tend to be painless and come on within seconds. The vision goes “black” or “gray” or “dim.” Some patients describe a “curtain over the eye” effect where the vision loss seems to close in from one direction.

“If there are positive symptoms like sparks and flashes and colors, that’s rarely a vascular occlusive event,” said Dr. Subramanian. Vascular TMVL has more negative symptoms. “If the dimness restores over the course of a minute or so, as what we presume is a little clot dissolving and the blood flow returning, that’s suggestive of vascular origin,” Dr. Subramanian said.

So, if a patient says, “My vision gets blurry sometimes and then it gets better,” the patient doesn’t have a retinal TIA. On the other hand, if he says, “I was fine, then had trouble seeing, then completely lost vision in 1 eye but it returned a minute or 2 later,” this should raise your suspicion that a vascular process is involved.

Assess risk factors. Take an inventory of the patient’s vascular risk factors, as outlined by Dr. Trobe (see “Warning sign”). If your patient is a 70-year-old with diabetes and hypertension, you’ll probably fall on the side of assuming it’s vascular until proven otherwise. You should also examine the patient for any vascular signs, perhaps a residual clot in the retina, though most often there is nothing.

Rule out GCA. The most important thing at this point is to make sure that any patient over age 50 does not have giant cell arteritis (GCA). “Get 3 quick blood tests: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and complete blood count (CBC),” said Dr. Biousse. “If they are normal and the patient has a normal eye exam and no systemic symptoms of GCA (e.g., headache, jaw claudication, scalp tenderness, weight loss), then you can rule out GCA.” If the lab results are abnormal, you should investigate further and potentially treat the patient with steroids until you have a definite diagnosis.

Refer to a Stroke Center

If you’ve ruled out ocular causes or TMVL, the question remains: Do you obtain a workup for retinal TIA, and how do you do that?

At this point, follow the guidelines, Dr. Biousse stressed. “The guidelines from the heart and stroke associations are very clear. If you’re an ophthalmologist, do not get any workup. You’ve done the differential diagnosis and ruled out GCA; you’re done. This patient must go to a stroke neurologist promptly.” She urged ophthalmologists to send the patient immediately to the closest emergency department (ED) affiliated with a stroke center (see next page).

The main difficulty when one sees a patient with a retinal or cerebral TIA is to identify which patients are at very high risk of stroke or cardiovascular death. After any TIA, the risk of stroke is estimated at 10%-15% at about 3 months, explained Dr. Biousse. More than half of those patients who are going to have a stroke will have it within 48-72 hours of the TIA. “It makes no sense to wait a week for an MRI, because if the patient is still alive and has not had a stroke by then, there is a very good chance the patient will be fine,” said Dr. Biousse.

On the other hand, if the patient happens to be one who is at very high risk of stroke, you will have missed the opportunity to prevent it. “This is why we tell ophthalmologists to send the patient to a stroke center where the entire workup is done within 24 hours,” Dr. Biousse said.

Set Up a Referral Pathway

Seek a stroke center. The experts urge ophthalmologists to take the time today to identify the closest stroke center to their practice. (For more information, see the Internet Stroke Center locator.)

A stroke center is an urgent care facility in which there is 24/7 availability of neuroimaging and any ancillary testing necessary for a stroke patient and access to a stroke neurologist. “An enormous number of EDs in the United States have been certified as stroke centers,” said Dr Biousse. “Even in remote areas, it is completely worth it to tell the patient to drive 80 miles to a stroke center instead of going to the closest ED 25 miles away. The extra hour of transportation will save a lot of money and energy [in the end] by helping providers reach a definitive diagnosis, whereas a local workup by physicians who are not experts in stroke neurology will only delay appropriate management.”

Establish contact. “I recommend calling the stroke neurologist at the center and introducing yourself to establish a collaboration,” said Dr. Biousse. “Tell the stroke neurologist that you are a local ophthalmologist and that occasionally you will see a patient with a retinal TIA (or central or branch retinal artery occlusion) and that you will tell the patient to come to his or her ED immediately for a stroke workup. Ask the stroke specialist to confirm that he or she will take care of your patient.”

Dr. Biousse added, “Sometimes ophthalmologists will say that they can’t send their patients to the ED because the ED does not want them, but it’s because they are sending the patients to the wrong ED. Send them to one affiliated with a stroke center. A stroke neurologist will know that you are following current guidelines.”

How to handle urgent referrals. If you see a retinal TIA patient within 1-2 days of the TMVL episode, the patient should be sent to the ED immediately, Dr. Biousse said.

When this happens, have a staff member call the ED triage nurse or the preestablished contact person to say that you’re sending over a patient who has had a “stroke in the eye” for an immediate workup and treatment by stroke neurology. Dr. Subramanian recommended sending the patient with a brief note, along the lines of “This patient had TMVL that I suspect is from ischemia. Patient has the following risk factors. Please evaluate for stroke risk.” The stroke specialist will know you are not overreacting, Dr. Subramanian reiterated.

What if a week has passed? Ophthalmologists often see patients 1 week or more after the retinal TIA episode, and it can be more difficult to know what to do in these instances.

If the patient has had recurrent episodes of TMVL or has major cardiovascular risk factors (such as a recent myocardial infarction or known arrhythmia), Dr. Biousse still sends the patient to the ED. In other situations, she just calls the stroke neurologist she works with (or the one on call) and asks him or her what is best and most efficient. “The answer will vary greatly depending on where you work, who is on call, what day of the week it is, and what time it is,” said Dr. Biousse. “As long as the stroke neurologist agrees to see the patient within a day or 2 and helps coordinate the necessary tests, I am fine waiting.”

Even so, Dr. Biousse always starts the patient on an antiplatelet agent and warns the patient about stroke symptoms and signs. She gives the patient the address of the closest stroke center and tells him or her to go to the affiliated ED immediately if another episode of TMVL occurs or any neurologic symptoms are noted. Dr. Subramanian manages his patients in a similar manner.

What the patient can expect. When patients arrive at the ED saying they’ve had a “stroke in the eye,” they are immediately put in a bed, often in the ED. They can expect to receive cardiac monitoring right away, along with blood tests, an EKG, and a consultation with a stroke neurologist. Within the next 23 hours, they will have brain and vascular imaging.

Depending on the evaluation, the patient may then undergo echocardiography to look for a cardiac source of emboli and, at the same time, the aortic arch will be evaluated. If one of the tests is abnormal, the patient will immediately be admitted to a stroke unit and treated appropriately.

If all the tests come back negative, the stroke neurologist will make recommendations for medical treatment/secondary prevention of stroke, and the patient will be discharged with a scheduled follow-up with the neurologist. “The patient is safe, everything is done quickly, and the ophthalmologist doesn’t have to worry about getting any of those tests,” said Dr. Biousse.

Even though this approach might sound aggressive, the reality is that it is not, Dr. Biousse insisted. “It is the current recommended practice so that you can prevent a devastating neurological and/or cardiovascular event, without wasting your own time trying to evaluate something you are not trained to evaluate.” This advice is reflected in the Academy’s Retinal and Ophthalmic Artery Occlusions Preferred Practice Pattern.

A note on incidence. Dr. Biousse sees about 1-2 patients a week with TMVL. Of those, she sends maybe 1 a month to the ED. Dr. Subramanian estimated that a busy comprehensive practice may see 1 retinal TIA every 1-2 weeks.

Thus, there is no need to worry that you will overwhelm the local ED, Dr. Subramanian said. Instead, the experts advised, just focus on the quality of the initial clinical evaluation and slow down during this phase so that you can confidently rule out ocular causes.

___________________________

1 Helenius J et al. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(2):286-293.

2 Lee J et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(6):1231-1238.

3 Streifler JY et al. Arch Neurol. 1995;53:246-249.

4 Jetty P et al. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(3):661-667.

5 Lauda F et al. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;40(3-4):151-156.

6 Golsari A et al. Stroke. 2017;48:1392-1396.

7 Tanaka K et al. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(3):e151-e155.

___________________________

Dr. Biousse is Cyrus H. Stoner Professor of Ophthalmology and professor of neurology at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Subramanian is professor of ophthalmology, neurology, and neurosurgery; vice chair for academic affairs in ophthalmology; and chief of the Neuro-ophthalmology Division at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

Dr. Trobe is professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences, neurology, and neurosurgery, and co-director of the Kellogg Eye Center for International Ophthalmology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Relevant financial disclosures: None.

For full disclosures and the disclosure key, see below.

Full Financial Disclosures

Dr. Biousse GenSight: C.

Dr. Subramanian Quark: S; Santhera: S.

Dr. Trobe None.

Disclosure Category

|

Code

|

Description

|

| Consultant/Advisor |

C |

Consultant fee, paid advisory boards, or fees for attending a meeting. |

| Employee |

E |

Employed by a commercial company. |

| Speakers bureau |

L |

Lecture fees or honoraria, travel fees or reimbursements when speaking at the invitation of a commercial company. |

| Equity owner |

O |

Equity ownership/stock options in publicly or privately traded firms, excluding mutual funds. |

| Patents/Royalty |

P |

Patents and/or royalties for intellectual property. |

| Grant support |

S |

Grant support or other financial support to the investigator from all sources, including research support from government agencies (e.g., NIH), foundations, device manufacturers, and/or pharmaceutical companies. |

|

Evolving Perspectives

In 1995, the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) reported a high risk of recurrent TIAs or stroke after a first retinal TIA, with up to 24.2% of retinal TIA patients having had a stroke at 3 years.1 This risk was lower than that of patients who had a cerebral TIA, suggesting that retinal TIAs have a better prognosis.

“Although the NASCET subanalysis was an excellent study, people really took to heart the idea that amaurosis fugax has a lesser risk of stroke than hemispheric TIA, contributing to the misconception that retinal TIAs are relatively benign,” said Dr. Subramanian. The NASCET data were interpreted accurately at the time, but our definitions of stroke and TIA have evolved and make use of today’s imaging technology, he noted.

Remaining controversy. Dr. Trobe does not believe the data from the NASCET have been superseded. He recommended that patients with recent retinal TIA undergo carotid artery imaging and the rest of the evaluation for threatened stroke promptly, with an urgency that depends on how recent the vision loss episode was. “I do not agree that such patients need to go to an ED, but an internist or neurologist should be contacted at the time of the visit to an ophthalmologist and the disposition arranged then.”

Diverging opinions. Dr. Biousse respectfully disagreed with Dr. Trobe. She emphasized the recommendations of the Academy’s PPP as well as the guidelines of the American heart and stroke associations, which ask all nonstroke specialists to refer patients to the closest stroke center for suspected retinal (or cerebral) TIA. “Outpatient testing or referral to a patient’s primary care physician only delays appropriate management,” she said.

Point of consensus. “Whether an ophthalmologist insists on an outpatient workup or refers the patient to a stroke center or a hospital, we can all agree that it has to be immediate and that ophthalmology practices need to have a pathway in place for urgent referral,” said Dr. Subramanian.

Physician resistance. “When I give a talk, people often react quite aggressively,” Dr. Biousse said. “They become very defensive, saying ‘Ophthalmologists can’t do that.’ My answer is always, ‘I’m not asking you to do anything. I’m trying to make your life easier. I’m saying, ‘Congratulations, you’ve made the diagnosis. You’ve ruled out ocular causes. Now get the patient to the next appropriate point of care and you’re done. Don’t waste another minute of your time. Just get the patient to a stroke specialist promptly.’”

Perhaps some ophthalmologists are afraid of being wrong or being perceived as overreacting, Dr. Biousse said. Some may have concerns about overtaxing the system. And still others, unconsciously, may be trying to please their patients; no one wants to hear that they must go to the ER, especially when they feel fine.

Follow the guidelines. The Academy’s PPP, published in late 2016, clearly emphasizes that patients with acute retinal ischemia, not just retinal artery occlusion but also transient occlusion (i.e., retinal TIAs), must be sent to a stroke center, Dr. Biousse said. “Now that it’s published, it’s even more important for ophthalmologists to be aware of the recommendations and follow them.”

Patient acceptance. Dr. Biousse noted that she has never had a problem with a patient once she has explained that she is trying to prevent a potentially devastating neurological problem. “I tell them that I believe they may have had a stroke in the eye and that I am very concerned. I say, ‘The best way to handle the situation is for you to go to the following stroke center.’ I give them a letter saying they have had a stroke in the eye. This will eliminate any waiting time in the ED. I warn them that they will have to stay 24 hours but say that, after that 24 hours, they either will be admitted to the hospital and receive treatment for a life-threatening disease or will leave with appropriate medication and the reassurance that all tests have been done. Give me 24 hours of your time, and you will be well taken care of.”

Insurance concerns. If an ophthalmologist obtains an outpatient MRI for TMVL, there is a good chance the patient’s health insurance will deny the claim. On the other hand, if a patient is sent to an ED for suspicion of stroke, the insurance company will cover the cost of the tests. “If the patient has no insurance, it’s even more important to send the patient to a stroke center because the patient will have one shot of getting a comprehensive evaluation,” said Dr. Biousse. “Very often, results from outpatient ancillary testing and investigations are normal despite what may show up on DWI-MRI,” she pointed out. “The patient then had those expensive tests for nothing.”

___________________________

1 Streifler JY et al. Arch Neurol. 1995;53:246-249.

|

Further Reading

Biousse V. Acute retinal arterial ischemia: an emergency often ignored. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(6):1119-1121.

Easton JD et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2276-2293.

Jauch EC et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947.

Kleindorfer D et al. Which stroke symptoms prompt a 911 call? A population-based study. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(5):607-612.

Merkler A et al. Frequency of evaluation for stroke risk factors in patients with retinal infarction. Poster presented at: AHA/ASA International Stroke Conference 2018; Jan. 25, 2018; Los Angeles.

Siket MS, Edlow JA. Transient ischemic attack: reviewing the evolution of the definition, diagnosis, risk stratification, and management for the emergency physician. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2012;30(3):745-770.

|