By Kathryn S. Klein, MD, MPH, and Seth A. Biser, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from November/December 2009 and may contain outdated material.

Steven Rodriguez* was a 48-year-old man who presented to the ER with three days of redness, irritation and swelling in his right eye. He told the ER physician that he was not a contact lens wearer and that his eye had not suffered any trauma or chemical exposure. He was started on Polytrim (trimethoprim and polymyxin B) eyedrops and bacitracin ophthalmic ointment and was told to visit our clinic the next day for follow-up.

We Get a Look

When the patient arrived to see us, he had 20/200 vision in the affected eye, 2+ lid edema, and 4+ conjunctival chemosis and injection. The left eye had 20/20 vision and was completely white and quiet. He had no palpable preauricular nodes. We stopped the Polytrim and put him on Tobradex (tobramycin and dexamethasone) four times a day for presumed epidemic keratoconjunctivitis.

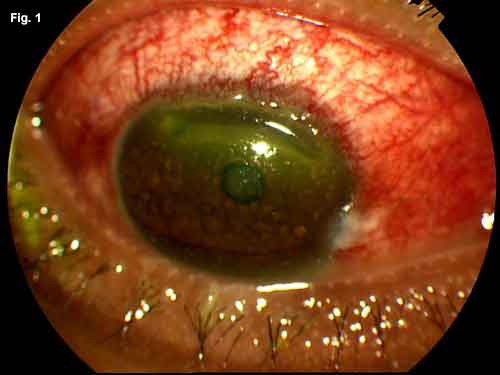

Two days later, Mr. Rodriguez returned to the clinic for follow-up. He was feeling somewhat better, and the BCVA in his right eye was now 20/40. However, we noted that he had persistent chemosis, follicles and a new 1.7 x 7.8 mm area of superior corneal thinning that spared the limbus. The area was about 80 percent thinned (that is, with 20 percent residual thickness). When we applied fluorescein, we noted pooling but no staining.

The Differential Diagnosis

The thinned area was initially thought to be a corneal dellen resulting from the large amount of adjacent chemosis. The Tobradex was stopped. The patient was given bacitracin and Vigamox (moxifloxacin) and was pressure-patched. The next day the area of thinning was largely unchanged, although it now stained with fluorescein. The thinning was avascular and spared the limbus. The patient reported mild photophobia but no pain.

At this time our differential was expanded to include Mooren’s ulcer, Terrien’s marginal degeneration and peripheral ulcerative keratitis due to a connective tissue disease (such as rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis [formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis], polyarteritis nodosa or systemic lupus erythematosus).

He had no history of joint pain or swelling, rashes, fevers, weight loss or sinus disease. A lab workup was sent to evaluate for autoimmune conditions, and he was sent home with artificial tears every hour, bacitracin ophthalmic ointment at night and an eye shield to be worn at all times.

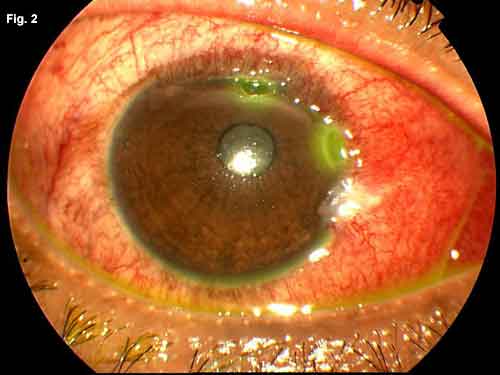

The next day, he developed a small amount of mucopurulent discharge. He was followed for five days while awaiting the lab results. During this time, he developed a second smaller area of peripheral corneal thinning superonasally; this was associated with an overlying epithelial defect.

The lab results. All the lab values were normal. C-reactive protein: 0.4; comprehensive metabolic panel: within normal limits; thyroid-stimulating hormone: 0.820; complete blood count: within normal limits, except for the white blood cell count, which was 7.0; erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 16; antinuclear antibody: negative; antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody: negative; C3 complement: 176; C4 complement: 28; hepatitis C: nonreactive; rheumatoid factor < 7; purified protein derivative: negative; and chest x-ray was normal.

He was referred to our cornea clinic. On the day of consultation, the cornea specialist made the diagnosis literally from across the exam room. He immediately observed that Mr. Rodriguez had a significant amount of mucopurulent discharge, greater than what previously had been noted in the clinic chart. The intensity of the discharge, together with the reported history of idiopathic corneal thinning, led to a presumed diagnosis of gonococcal conjunctivitis.

Corneal smears and bacterial cultures were obtained. The patient reported a history of gonorrhea as a teenager, which was treated with “an injection.” But he added that he had been married for more than 25 years in a monogamous relationship. He denied any urethral discharge or genital lesions. The Gram stain was positive for gram-negative intracellular diplococci.

Treatment

Because of the severe amount of corneal involvement, Mr. Rodriguez was admitted to the hospital for intravenous ceftriaxone. He was treated with frequent eyewashes with normal saline to remove infectious and inflammatory debris; oral doxycycline, 100 mg twice a day (both for its beneficial effects on the cornea and for concomitant treatment for Chlamydia); oral ascorbic acid, 2 grams per day; and Zymar (gatifloxacin) drops, four times a day, as well as bacitracin ophthalmic ointment at bedtime as prophylaxis against superinfection. Cultures grew out large amounts of Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

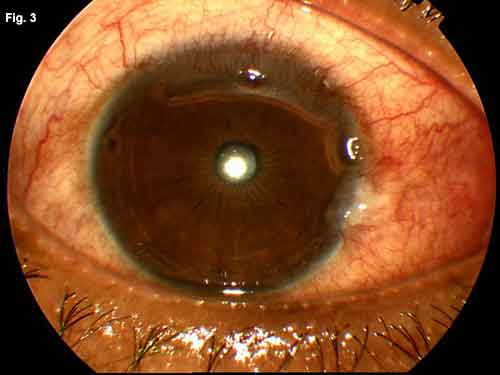

An infectious disease consult was obtained, and the case was reported to the CDC. Urethral cultures were negative for gonococcus. During the hospital stay, the thinned areas of cornea began to re-epithelialize. Corneal cultures demonstrated that the causative organism was sensitive to fluoroquin- olones. He was discharged home after five days on a two-week course of oral ciprofloxacin, doxycycline and ascorbic acid, as well as topical Zymar and bacitracin ophthalmic ointment. Eight days after hospital admission, the visual acuity had returned to 20/20, and over the next month the peripheral cornea returned to normal thickness.

|

|

|

WE GET A LOOK. Fig. 1: Two days after presentation to our clinic, the patient developed superior corneal thinning. Fig. 2: A second area of corneal ulceration developed while we awaited the lab results. Fig. 3: The patient's corneal ulceration improved after treatment with intravenous antibiotics.

|

Discussion

Causes of acute peripheral corneal thinning. The diagnosis can be challenging. Corneal dellens are excavations due to excessive dryness, but they are associated with obvious elevations of the adjacent conjunctiva, and typically respond rapidly to patching or lubrication. Active ulcerative keratitis associated with systemic inflammatory or vasculitic diseases is typically accompanied by an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or a known history of systemic disease. Mooren’s ulcer, which may be associated with hepatitis C, tends to present with significant pain and a gray marginal overhang of the thinned area, neither of which was present in our patient. Typically, Terrien’s marginal degeneration is slowly progressive rather than acute in nature. Patients may be asymptomatic. The corneal epithelium overlying the thinned area often remains intact.

Peripheral keratitis associated with hyperacute conjunctivitis is most commonly linked to infection with N. gonorrhoeae, but it has also been reported with B-hemolytic streptococci infection. Gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis usually has a hyperacute onset with large amounts of mucopurulent discharge. Conjunctival follicles and a positive preauricular node are also classic findings. While this disease carries a significant risk of perforation, it typically responds rapidly to treatment. In our patient, conjunctival discharge was not noted as a prominent clinical feature until several days after initial presentation. Apparently, this is not rare: Ullman and colleagues report that in their study of 47 cases of ocular gonoccocal infections, the average time to treatment with parenteral antibiotics for conjunctivitis was three days. In contrast, the average time to treatment with parenteral antibiotics in the severe keratitis group was nine days. Five of six cases of corneal perforation were initially treated inadequately with only topical therapy. Prolonged time to diagnosis was associated with more severe corneal disease.1 In our patient’s case, the initial treatment with bacitracin may have suppressed the mucopurulent response, but once bacitracin was stopped, the discharge became a prominent clinical feature, aiding in the correct diagnosis.

Treatment. While intramuscular antibiotic treatment can be used for acute gonococcal conjunctivitis, patients with corneal thinning should be considered for intravenous therapy. The CDC now recommends the use of a third-generation cephalosporin over a fluoroquinolone as initial systemic therapy because of increasing rates of fluoroquinolone resistance. Because of the high frequency of co-infection with Chlamydia,patients should be treated with an appropriate regimen (either a one-time, 1-g dose of azithromycin, or doxycycline 100 mg, twice a day for seven days).2

High level of suspicion. In addition to the classical hyperacute presentation with copious mucopurulent discharge, gonococcal conjunctivitis is often associated with gonococcal urethritis, and the genital symptoms usually precede the ocular symptoms by a week or two. Because the ocular disease can initially present in a less acute manner, however, it must remain on the differential for persistent or worsening conjunctivitis in newborns and sexually active adults. Rarely, urethritis may not be present, due to direct inoculation of the organism into the eye.

The human factor. All cases of Neisseria infection must be reported to the CDC. Infectious disease consultation should be obtained where possible, to rule out other sexually transmitted diseases and to provide counsel to partners. Owing to the sensitive issues involved, dialogue with the patient and any partners must involve tact and respect for privacy.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Ullman, S. et al. Ophthalmology 1997;94:525–531.

2 CDC. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56:332–336.

___________________________

Dr. Klein is a third-year resident at New York University. Dr. Biser is a clinical assistant professor at NYU department of ophthalmology.