This article is from August 2012 and may contain outdated material.

Although it may be challenging to define and diagnose normal-tension glaucoma (NTG), as noted in Part One of this update (published last month), the approach to its treatment is more straightforward.

Experts agree that, even though the IOP of patients with NTG is consistently within the statistically normal range, their treatment is similar to that of patients with high IOP. “The only thing we know to do is lower the pressure,” said Leon W. Herndon, MD, associate professor of ophthalmology at Duke University Eye Center in Durham, N.C. “These patients, by definition, need lower pressures to maintain their visual field.”

Setting the IOP Goal

How low can you go? The Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study (CNTGS) showed that a 30 percent reduction in IOP can prevent progression of visual field loss in most patients with previously documented progression or a fixation threat.1

However, Keith Barton, MD, suggested that the numbers game has a limit. In a patient with advanced glaucoma, Dr. Barton is satisfied if the pressure can be lowered to 8 or 9 mmHg, but he doesn’t set that as a target level because the numbers are not evidence based. Dr. Barton is a consultant ophthalmic surgeon of the glaucoma service at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London. He added, “The lowest target level that is evidence based is probably less than 15 mmHg, though I would often recommend a pressure of 10 to 12 mmHg in patients who are found to progress in the teens, especially if they have sight-threatening visual defects.” Dr. Herndon agrees. “I don’t say we need to get you down 30 percent,” he said, noting that at some point, you run the risk of hypotony.

Typically, Dr. Herndon establishes a range in the low teens or high single digits. “The bottom line: Try to get it down as low as you can safely get it down, and follow the patient. If things are getting worse based on visual field or structural testing, then aim even lower.” But, he warned, “If you get the pressure down too low, you might have to deal with another set of problems.”

“Eye pressure limbo” is what Sayoko E. Moroi, MD, PhD, calls the pursuit of an ideal low pressure in patients who are already in the normal range. “With NTG, it’s physiologically impossible with medical therapy to go below episcleral venous pressure of 8 to 12 mmHg. I try to get down to 5 to 8 mmHg with surgery, as long as I’m not creating hypotony-related symptoms.” Dr. Moroi is associate professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences, glaucoma service chief, and glaucoma fellowship director at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

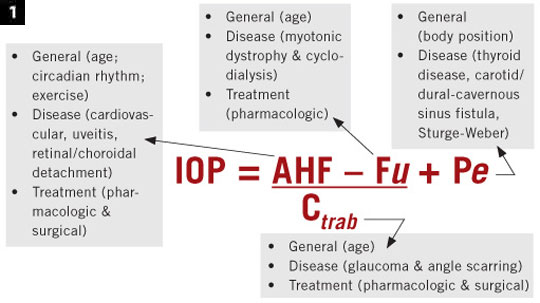

Use the formula. IOP is a complex quantitative trait, so Dr. Moroi uses a modified Goldmann equation (Fig. 1) to keep the contributing factors in mind in setting a goal. “Pressure is a number we see on our instruments, but it reflects a complex physiology of aqueous inflow, aqueous outflow through the uveoscleral pathway and trabecular pathway, and episcleral venous pressure,” she said. When aqueous inflow and uveoscleral outflow are “in balance,” what’s left is episcleral venous pressure. “So, how low can you go with medication? As low as episcleral venous pressure, which is in the range of 8 to 12 mmHg.”

Confirm progression. Visual fields must be confirmed more than once, said Douglas R. Anderson, MD, who participated in the CNTGS. He added that IOP should be measured at least twice before starting treatment because of the possibility of regression to the mean.

Dr. Anderson, who is professor emeritus of ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, explained that because some eyes do not receive treatment that might be beneficial, the CNTGS was designed to recognize the smallest increment in progression. The protocol required three visual field tests at the start. He emphasized that, without having that baseline, you wouldn’t know the variability of the patient’s readings.

Even more important, the CNTGS suggests that patients need to be tested multiple times to confirm suspected change. Other studies have corroborated this observation, Dr. Anderson said. “More fields are required than intuition would tell you.”

Subsequently, researchers created a simulated model of progression and arrived at a benchmark of six visual fields over two years.2 “With fewer than six visual fields and less than two years, you’re walking on very uncertain ground,” Dr. Anderson said. “The disease moves slowly; it’s like watching grass grow. So you’ll have to allow enough time between tests.”

The key message: Confirm suspected progression, with at least a second and third visual field test, to be sure that it is genuine. Once is not enough.

Consider the treatment options. Treatments for NTG are the same as for primary open-angle glaucoma. “Drugs, laser, surgery,” Dr. Herndon said. However, he tends to monitor his NTG patients more closely.

Slow down. The CNTGS found that half of the untreated group never experienced progression, which suggests that there is ample time to consider the various treatment options, at least in mild cases. “It may be all right to see how things go, realizing that half never progress, and if they do, they may progress slowly,” Dr. Anderson said. He advised monitoring without treatment until progression and rate of deterioration become apparent.

Until there’s a way to predict which patients are at higher risk for disease progression, the best strategy may be conservative management, especially in mild cases, said Dr. Anderson. “However, if a patient is first seen with severe disease and impending or actual visual impairment, assertive treatment should be undertaken without waiting.”

|

|

Complexity of IOP. Modified Goldmann formula showing the factors that contribute to IOP. Abbreviations: AHF, aqueous humor inflow; C, outflow facility through the trabecular meshwork; Fu, uveoscleral outflow; Pe, episcleral venous pressure.

|

Drug Treatment

Of course, some patients will require medication. If further IOP lowering is needed, Dr. Moroi sets a target IOP range of 8 to 12 mmHg, which is at episcleral venous pressure. This can be achieved in some patients by maximally targeting outflow with prostaglandins and inflow with (in order of preference) beta-blockers, alpha2 agonists, or carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs).

Dr. Barton tends to use prostaglandins as first-line therapy. Beta-blockers are a second-line choice, with or without CAIs. He said, “I am not a big fan of alpha agonists because of poor long-term tolerance and poor diurnal pressure control.”

A case against beta-blockers. Because systemic hypotension is part of the NTG patient profile, Dr. Moroi exercises caution in using beta-blockers, which could decrease ocular perfusion pressure and thus lead to further disease progression. If she is considering use of a beta-blocker, she first checks the patient’s blood pressure and pulse. If the systolic pressure is below 100, she thinks twice about prescribing a beta-blocker or alpha2 agonist (such as brimonidine) and might consider a CAI.

If the patient’s pulse is in the 50s, Dr. Moroi advises nasolacrimal occlusion to minimize systemic absorption of the drug. She also considers a gel formulation to keep the medication on the ocular surface and thus decrease systemic absorption.3

Timolol and brimonidine. Dr. Barton tends to use timolol because of its potent IOP-lowering effect. However, he is less likely to use it at night “because of lack of nocturnal efficacy and possible hypotensive effect that might compromise ocular blood flow.”

The Low-pressure Glaucoma Treatment Study (LoGTS) showed that patients with NTG treated with the alpha2-adrenergic agonist Alphagan-P (brimonidine tartrate 0.2 percent) were less likely to have visual field progression than patients treated with the beta-adrenergic antagonist Istalol (timolol maleate 0.5 percent): The progression rates were 9.1 and 39.2 percent, respectively.4 However, the IOP-lowering effect was similar for the two drugs, which may indicate that brimonidine works in an IOP-independent fashion to maintain the health of the optic nerve. (The study was funded in part by Allergan, the manufacturer of brimonidine.)

The suggestion that brimonidine may be neuroprotective “is pretty exciting,” said Dr. Herndon. However, he added, “I wouldn’t say brimonidine is my go-to drop right now in NTG,” explaining that it doesn’t get pressure as low as prostaglandins or beta-blockers do. “But LoGTS is compelling enough that I am reconsidering my regimen.”

There is a caveat: 28.3 percent of brimonidine participants discontinued the study because of drug-related adverse events, compared with only 11.4 percent of timolol recipients. Dr. Herndon has observed better tolerance with the proprietary formulation (Alphagan-P) than with the generic.

Treatment Pearls

DR. ANDERSON: On average, six visual fields over two years are required to detect and ascertain moderately fast progression. With fewer fields and less time, progression may appear to exist when not present—and true progression may be missed.

DR. BARTON: In determining the appropriate degree of treatment, it is sometimes helpful to remember how high the IOP was initially. However, this may be irrelevant in advanced glaucoma because the treatment target IOP level would be the same.

DR. HERNDON: One eye usually has more damage than the other. Try to address the more affected eye first. And remember that it may need a different treatment from that of the better eye.

DR. MOROI: For a patient whose optic nerve has a very suspicious appearance, accompanied by early visual field loss, I would initiate treatment but make sure that the treatment does not accelerate progression. And if you’re going the surgical route, don’t aim for clinical hypotony.

|

Surgery

When medication isn’t enough. Patients with IOPs around 10 mmHg and average central corneal thickness have been referred to Dr. Barton for filtration surgery. “When this happens,” he said, “I question the validity of the diagnosis of progression, as I think it highly unlikely that a patient would progress if the IOP is truly at this level.”

On the other hand, he has operated on patients whose pressures were in the low teens. “Often, these are patients whose central corneal thickness is thinner than average, indicating a higher true pressure. I have also operated at this level if IOP control has been erratic or if compliance is suspected to be poor.”

In general, if diurnal IOP is consistently at 12 mmHg or less, Dr. Barton doesn’t recommend filtration surgery “unless there is clear evidence of progression or poor compliance.”

Dr. Herndon will operate if the patient’s disease worsens while IOPs are low. “You’ve got to get the pressure lower. I’m aiming for single digits,” he said. “The only therapeutic option out there for single digits is trabeculectomy.” Most of his patients remain stable for years after surgery.

Laser. “Laser trabeculoplasty is another option,” said Dr. Anderson, noting the consensus that laser is about equal in efficacy to single-drug treatment. Although Dr. Anderson tends to start patients on drops, he said, “There’s plenty of scientific literature to support that it’s all right to recommend laser first. Laser is just as good as a single type of eyedrop.”

According to Dr. Herndon, “Laser may not get pressure lower during the day, but it may limit diurnal fluctuation of pressures.” He achieves greater percentages of reduction with laser, if he initiates treatment at 25 mmHg rather than 15 mmHg.

Bottom line: Reduce IOP. “To me, glaucoma in the setting of normal IOP is still an enigma,” Dr. Moroi said. “But I feel responsible to minimize any pressure contribution to optic nerve progression by getting their pressure as low as safely possible.”

___________________________

1 Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126(4):487-497.

2 Chauhan BC et al. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(4):569-573.

3 Shedden AH et al. Doc Ophthalmol. 2001:103(1):73-79.

4 Krupin T et al. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(4):671-681.

___________________________

Dr. Anderson is a consultant for Carl Zeiss Meditec. Dr. Barton has received lecture honoraria from Allergan and Pfizer; is on the advisory boards of Alcon, Amakem, Glaukos, Kowa, Merck, and Thea; is a consultant for Alcon, Aquesys, Ivantis, and Refocus; has received educational grants or funding from Alcon, AMO, Merck, New World Medical, and Refocus; and owns stock in Aquesys and Ophthalmic Implants (PTE).Dr. Herndon is on the glaucoma advisory board for Alcon. Dr. Moroi receives research funds from Merck.