This article is from October 2012 and may contain outdated material.

Vitreous liquefaction and posterior vitreous detachment (PVD), normal markers on the road to old age, usually proceed uneventfully and in step with one another. The gelatinous extracellular matrix of the vitreous collapses and the adhesiveness of the vitreoretinal interface weakens, allowing the vitreous to detach cleanly.

Sometimes, though, missteps along this pathway can threaten patients’ visual acuity. If vitreomacular adhesion (VMA) stays strong and there is an incomplete PVD, then tractional forces endanger the macula. But the standard treatment for vitreoretinal complications, surgical vitrectomy, is generally considered too risky during the earliest stages of this process. The customary prescription for these patients: Go home and hope for improvement.

Soon, however, ophthalmologists might be able to offer them a new option: pharmacologic vitreolysis.

Enter Ocriplasmin

Ocriplasmin (previously known as microplasmin) is a recombinant, truncated form of a proteolytic enzyme that can dissolve the sticky protein glue in the vitreoretinal interface. After more than a decade of testing, it is poised to become the first FDA-approved agent for pharmacologic vitreolysis.

If the FDA’s OK comes this month, as anticipated, ocriplasmin will be available by the first quarter of 2013 and sold under the brand name Jetrea, said Patrik De Haes, MD, chief executive officer of ThromboGenics. Although the price has not yet been set, it is expected to cost about $2,000 per dose, Dr. De Haes said.1

Approved use. The FDA-approved indications for the drug are expected to be narrow: a single intravitreal injection of 125 µg to treat symptomatic VMA (also known as vitreomacular traction, or VMT) in patients with or without macular hole. But it would not be surprising if clinicians also tried ocriplasmin for a wide variety of other conditions related to incomplete PVD, said Pravin U. Dugel, MD, a vitreoretinal subspecialist in private practice in Phoenix. “We are very familiar with injecting now. Plus, we have an accumulation of a decade’s worth of data on this drug in almost 1,000 patients, and in all studies, the safety profile has been outstanding.”

Efficacy. Despite its trailblazing nature, the drug had success rates of much less than 50 percent in meeting most of the desired endpoints during the largest clinical trials. “The major downside that we know of is that the drug is less powerful than we would like,” said Mark W. Johnson, MD, professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences and director of the retina service at the University of Michigan’s Kellogg Eye Center.

ThromboGenics conducted two multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase 3 trials (652 eyes) to compare a single 125-µg dose of ocriplasmin with a placebo injection in patients with symptomatic VMA. The pooled results include the following:2

- Pharmacologic resolution of VMA occurred in 26.5 percent of treated subjects at day 28, compared with 10.1 percent of the placebo group (p < 0.001). Those figures increased to 34.5 percent and 14.3 percent, respectively, when subjects with an epiretinal membrane were excluded from the analysis (p < 0.001).

- Among treated patients, 13.4 percent had induction of total PVD, versus 3.7 percent of the controls (p < 0.001).

- Among patients who had a baseline BCVA worse than 20/50, 25.1 percent of the treatment group gained three or more lines of BCVA, compared with 11.4 percent of controls.

- Among treated patients, 40.6 percent had pharmacologic closure of a full-thickness macular hole at day 28, versus 10.6 percent of controls (p < 0.001).

|

|

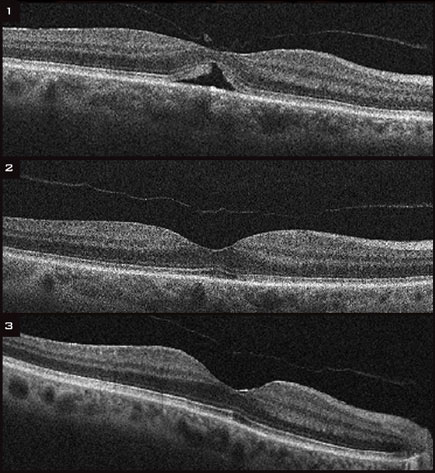

(1) Before treatment, OCT showed an impending macular hole in the left eye of a 73-year-old woman. At this time, her VA was 20/63. (2)Six months after a single injection of ocriplasmin, her VA had improved to 20/40. (3) Thirty-six months after the injection, her VA had improved to 20/25.

|

Safety Issues

Good news: minimal adverse events. Until the FDA’s Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee considered ocriplasmin in July, the only available safety data supported the view that adverse ocular events were mild and limited largely to the first postinjection week.

For instance, in one placebo-controlled study (n = 188), 12.9 percent of the 110-person treatment group had floaters in the first week; this declined to 3.9 percent at six months.3

Worrisome news: unexplained visual loss. However, at the July advisory committee meeting, some panel members expressed concern after learning that 7.7 percent of ocriplasmin-treated patients had experienced unexplained visual losses. Most subjects regained the lost acuity by two weeks postinjection, but in a few cases, the losses persisted for up to six months, ThromboGenics reported.

During the meeting, Wiley Chambers, MD, deputy director of the agency’s Division of Transplant and Ophthalmology Products, said that his office has asked ThromboGenics to provide further data on a “relatively large” number of treated patients with 15-letter losses of VA. Dr. Chambers noted that his office had analyzed the data on affected subjects to eliminate possible confounding factors. “But then I was left with a series of patients that, at least based on the interventions, had a 15-letter loss at some time during the trial for which we don’t have an immediate explanation,” he said. “Is there some process going on that is causing the decreased vision, or is it potentially a real phenomenon that causes harm?”

Some committee members called for the agency to require postmarketing studies to clarify this issue. Even so, the panel unanimously agreed that the evidence shows ocriplasmin is an effective treatment for VMA and that the drug’s potential benefits outweigh the possible risks.

Dr. Johnson recommended withholding final judgment on safety until the unexplained VA losses are better understood. “These patients regained their vision eventually, but we don’t have a clear understanding of what happened.”

Pipeline Report

Competitors that failed. Myriad compounds have been tested for effectiveness at pharmacologic vitreolysis, but most quickly faltered, according to a review published last year.1 These agents include bacterial collagenase, hyaluronidase, dispase, and plasminogen activators such as tPA and urokinase.

An oligopeptide-based molecule called Vitreosolve (Vitreoretinal Technologies) made it all the way to a phase 3 clinical trial in 2008-2009 before investors balked at spending another $40 million to achieve statistical significance, said Vicken H. Karageozian, MD, chief technology officer for the company. The trial was abandoned, and the company is defunct.

“The decision was made that even though the drug worked in about 50 percent of the patients, we would suspend work on it,” Dr. Karageozian said. He and other principals in that company went on to found Allegro Ophthalmics, which now is pursuing ALG-1001 (see below).

The review paper identified plasmin as the most widely studied vitreolytic agent. Individual surgeons sometimes inject it in hopes of making difficult surgical vitrectomy cases easier. But plasmin is not commercially available, and it degrades rapidly.1

The molecule that Dr. Johnson said he would most like to see investigated further is chondroitinase. In early tests, the enzyme was particularly good at dissolving the vitreoretinal adhesion. “It had the ability to separate the vitreous entirely, including at the base. It appears to be an ideal agent, but the company did not develop it.”

ALG-1001: a competitor with promise. It is likely to be at least three years before ocriplasmin has any company in this class of drugs. That competition could come from ALG-1001, a synthetic anti-integrin oligopeptide that inhibits cell adhesion. If ALG-1001 proves safe and effective, it would come to market as early as 2016, according to the company’s projected timetable.

ALG-1001 binds to multiple integrin-receptor sites on cells, preventing adhesion and promoting development of a PVD. In rabbit studies, the peptide completely liquefied the vitreous in 80 percent of injected eyes within a day and produced total PVDs in 60 percent, the company reported this spring.2 The first human study found that ALG-1001 caused complete PVD in six of 15 treated patients and partial PVD in two.2

However, integrin receptors are also implicated in molecular pathways that lead to choroidal and preretinal neovascularization. Consequently, the molecule’s initial clinical study has vitreolysis only as a secondary endpoint. The trial will test the drug for use as an adjunct to anti-VEGF injections for wet AMD or diabetic macular edema.

___________________________

1 Schneider EW, Johnson MW. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1151-1165.

2 Boyer DS. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology; May 8, 2012; Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

|

Anticipated Applications

For retina subspecialists. Response in the vitreoretinal community ranges from eager anticipation to cautious optimism. “I think the drug has the potential to be a game-changer,” Dr. Dugel said. “It’s not like it’s a better mousetrap. Right now, there is no mousetrap. It will be the only drug in this field.”

Steven D. Schwartz, MD, professor of ophthalmology and chief of the retina division at UCLA’s Jules Stein Eye Institute, said he welcomes a pharmacologic agent that will relieve traction on the retina and induce a PVD, even if the drug has intermittent success. He added that some patients can be “quite young, age 35 and up—people for whom a permanent loss of vision would impact them for many years. Pharmacologic vitreolysis allows these patients a chance for resolution of their issues without surgery.”

For comprehensive practices. Ocriplasmin also may prove to be transformative for comprehensive ophthalmology, Dr. Johnson said. “As we get into the pharmacological era, we’ll have the potential to intervene and prevent these conditions in some eyes. In other cases, we’ll be able to intervene at an earlier stage than we do now.” As a result, he said, “general ophthalmologists will have to be aware of the group of disorders that we consider complications of the process of vitreous detachment. They must recognize these disorders and refer the patients for therapy in a timely fashion.”

Front-line ophthalmologists will have to rely on their knowledge of signs and symptoms to do so, however, as definitive diagnosis relies on optical coherence tomography (OCT), Dr. Johnson said. “A general ophthalmologist might suspect one of these problems at the slit lamp, but you can’t usually see it without OCT.”

What Lies Ahead

Studies under way. The ClinicalTrials.gov website lists at least 15 studies of various other uses for ocriplasmin, including whether serial injections increase the proportion of patients who achieve a complete PVD; if the drug reduces macular edema caused by uveitis; and if pretreatment with the drug facilitates surgical vitrectomy in two difficult groups, premature babies and diabetics.

Widespread usage? Despite ocriplasmin’s limitations, as long as the drug has a good safety profile, its uniqueness and ease of use will make pharmacologic vitreolysis an everyday event in ophthalmology, the three vitreoretinal experts predicted.

It will take some time to sort out the issue of when to use an expensive drug and when not to do so, Dr. Johnson said. “If I tell the patient there’s a 1 in 5 chance of the drug working, he’ll probably say, ‘Sure, I’ll take that chance as long as it’s not going to harm me.’ But if I say there’s a small-percentage chance that the drug could cause a major drop in your vision, or if I tell you that it’s going to cost you a few thousand dollars, then you might decide just to go straight to surgery.”

It’s important to note that some potential benefits of ocriplasmin can help patients right away, Dr. Dugel said. “If you have a patient with a small to medium macular hole—250 microns or smaller—we know that with one injection there’s a 50 to 60 percent chance of its closing without ever requiring surgery. When you tell the patient that, why wouldn’t the patient take that opportunity?”

Dr. Schwartz thinks that the drug will find immediate acceptance. “It’s going to be a presurgery drug, an ‘instead of surgery’ drug, and a drug for people who are not candidates for surgery.”

___________________________

1 The drug will be sold in the United States by ThromboGenics and abroad by Alcon.

2 Stahlmans P et al. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:606-613.

3 Kuppermann BD. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology; May 8, 2012; Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

___________________________

Dr. Dugel was an investigator in the ocriplasmin trials and receives consulting and speaking fees from ThromboGenics and Alcon. Dr. De Haes is an employee of ThromboGenics. Drs. Johnson and Schwartzreport no current financial interests; they previously participated in now-completed ocriplasmin trials. Dr. Karageozian is an employee of Allegro Ophthalmics.

Further Reading

Johnson MW. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(3):371-382.e1. Review.

Wolf S, Wolf-Schnurrbusch U.Ophthalmologica. 2010;224(6):333-340. Review.

Sebag J. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242(3):690-698. Review.

|