By Debarshi Mustafi, BS, Virginia M. UTZ, MD, James H. Bates, MD, David B. Pugh, MD, and Johnny Tang, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from July/August 2011 and may contain outdated material.

Donald Jacobs* is a 45-year-old man who presented to his local ophthalmology clinic with a four-day history of painless, decreasing vision in his left eye. He was referred to our retina-uveitis service for subsequent evaluation. His past medical history included hypertension and type 2 diabetes, but with poor compliance to his prescribed medication. The review of systems was significant only for a left-sided headache, which had been present since he first noticed the decline in vision. His social history was also significant for multiple sexual partners. On presentation, he was found to be hypertensive (160/90 mmHg), but no other systemic examination findings were present.

Initial Exam

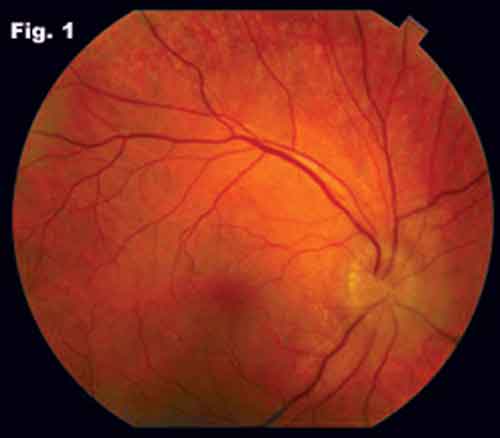

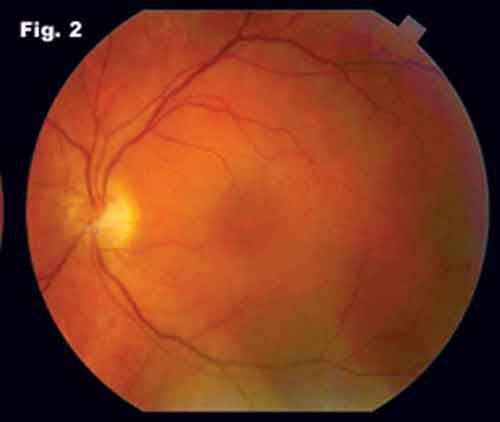

When we saw Mr. Jacobs, his visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and counting fingers at 2 feet in the left eye. The anterior segment exam was significant for 3+ cells and flare in the left eye. The dilated fundus exam was significant for vitreous cells and haze in the left eye and optic nerve edema in both eyes—2+ in the right and 1+ in the left (Figs. 1 and 2). In the left eye, we noted small (1–2 mm), white subretinal infiltrates inferiorly in the periphery. The pupillary exam was significant for a relative afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. His IOP was within normal limits, and his extraocular movements were full and nonpainful.

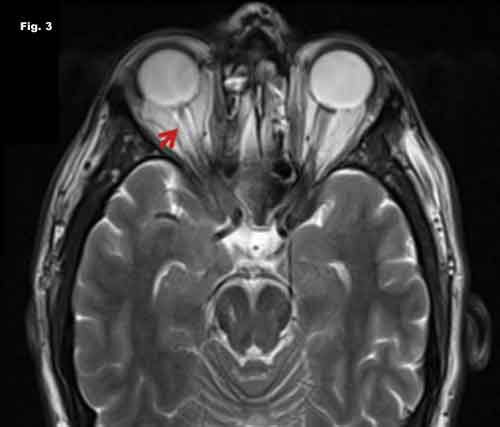

The patient’s blood pressure was medically lowered, but his bilateral optic nerve edema persisted. MRI revealed increased signal intensity of the optic nerve in the right eye (Fig. 3). No other white matter lesions were noted on MRI imaging. We ordered serologic tests, including HIV, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), hepatitis B and C panel, Epstein-Barr virus serology, mycobacteria serology, Bartonella henselaeserology, Lyme titers and serology, HSV-1 and -2, IgM, ESR, CRP, ANA, ANCA and ACE level. A PPD, chest x-ray and lumbar puncture were also completed.

Lab results. Serological testing was remarkable for positive Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) tests. The cerebrospinal fluid VDRL was negative, and the FTA-ABS in the CSF was inconclusive.

Serological testing remains the mainstay of laboratory diagnosis of primary, secondary and tertiary syphilis. In our case, the positive VDRL and FTA-ABS tests confirmed that the patient’s ocular condition was a manifestation of tertiary syphilis.

Treatment. When treatment is initiated expeditiously, ocular manifestations of neurosyphilis may completely resolve.

Treatment was 24 million IU of intravenous penicillin G daily for 10 days. He was then maintained on a 2.4 million IU intramuscular dose of the drug for three weeks. The patient’s vision improved to 20/40 in the left eye after one week. Both the patient and his current partner were counseled, and the partner was provided with appropriate referral and treatment.

|

|

|

Initial Exam. We noted nerve inflammation in the right (Fig. 1) and left (Fig. 2) eyes.

|

|

|

MRI. A T2-weighted sequence shows inflammation of the optic nerve sheath (Fig. 3).

|

Discussion

Common confounders. Mr. Jacobs’ neuroretinitis could be due to infectious as well as noninfectious etiologies. In addition to syphilis (Treponema pallidum), infectious etiologies for neuroretinitis include cat-scratch disease (Bartonella henselae), trench fever (B. quintana), Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) and tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis). Noninfectious conditions that may cause the optic nerves to have a clinically similar appearance include hypertensive retinopathy, pseudotumor cerebri and intracraninal arteriovenous malformations, as well as typical masqueraders such as sarcoidosis, polyarteritis nodosa and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

A disease with three stages. The World Health Organization lists syphilis as a persistent public health problem, despite affordable diagnostic tools and simple antibiotic regimens. The causative organism in syphilis is the spirochete T. pallidum, which most commonly enters the body via breaks in the skin or through mucous membranes during sexual contact. The primary lesion, a painless, infectious chancre, can heal in two to six weeks without treatment. In secondary and tertiary stages, which can occur years after primary infection, more systemic involvement is seen as the organism spreads throughout the body, even infiltrating the central nervous system.1

Maintain a high degree of suspicion. Ocular syphilis, although uncommon, is a diagnostically important manifestation of the disease.2 The most common ocular symptom in patients suffering from tertiary syphilis is uveitis, but the presentation is similar to other ocular inflammatory conditions due to the lack of pathognomonic signs in syphilis. This necessitates a high degree of suspicion and appropriate testing to accurately diagnose and, ultimately, treat the condition. Prospective studies of the natural history of the disease have revealed that about one-third of all patients affected with syphilis will develop tertiary symptoms such as ocular manifestations. The most common presenting symptoms of tertiary syphilis are visual changes and headache; however, uncommon findings may be the sole manifestation of the disease.

Ocular involvement of tertiary syphilis can affect any part of the eye. Optic neuritis may manifest either unilaterally or bilaterally, and can take any form, ranging from retrobulbar neuritis to papillitis, to perineuritis, to the neuroretinitis seen in this patient. The optic neuritis seen in syphilis does not have a characteristic clinical picture and cannot be distinguished from other infectious and noninfectious causes. Thus, syphilis testing is necessary in cases of optic neuritis.

Correct diagnosis. The diagnosis of syphilis involves clinical history, examination of any active lesions for treponemas and serological testing for syphilis, which is the most commonly used testing method. These tests are divided into nontreponemal tests (such as the VDRL test), which are useful for screening, and treponemal tests (such as the FTA-ABS), which are more sensitive and used to confirm the diagnosis. In the case of neurosyphilis, there is no one definitive method, and diagnosis relies on clinical findings, serological testing and, if necessary, CSF cell counts and protein levels or a reactive CSF VDRL.

Treatment. Syphilis responds very well to antibiotics, and penicillin remains at center stage. There is concern that therapeutic levels may not be achieved in the eye, so penicillin can be coadministered with probenecid to increase the ocular concentration and intraocular half-life. If the patient has a penicillin allergy, doxycycline may be substituted or penicillin desensitization may be attempted. It is important to administer the antibiotic correctly to eliminate the organism completely from the eye; otherwise, it may persist and cause repeat attacks after a latency period. With proper antibiotic therapy, the visual prognosis is very good for patients with ocular complications of tertiary syphilis. Patients should be tested periodically with VDRL to see if there is a decline in the titers, indicating adequate response to the regimen.

Conclusion. Given its persistence as a public health problem, syphilis should always be considered in the differential when thinking of infectious etiologies. This case highlights how nonspecific visual symptoms can be in tertiary syphilis and how accurate testing and appropriate antibiotic treatment can often restore a patient’s visual acuity to near baseline levels.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Smith, G. T. et al. Postgrad Med J 2006;82:36–39.

2 Chao, J. R. et al. Ophthalmology 2006;113:2074–2079.

___________________________

Mr. Mustafi is a medical/PhD student; Dr. Utz is a third-year resident of ophthalmology; Dr. Pugh is senior clinical instructor of ophthalmology; Dr. Bates is associate professor of ophthalmology and Dr. Tang is the associate ophthalmology residency program director; all are at University Hospital Eye Institute, Case Western Medical Center and its affiliates.