Download PDF

With the benefit of substantial numbers of cases, uniform data collection, and rigorous isolation of risk factors, a retrospective database study of electronic medical records (EMRs) has deepened ophthalmology’s understanding of the incidence of macular edema after cataract surgery.1

Data collection. Researchers in the United Kingdom mined a database of nearly 82,000 eyes that had undergone phacoemulsification at 8 National Health Service (NHS) sites over 4 years—making this the largest clinical study ever published on pseudophakic macular edema (PME).

The researchers capitalized on the NHS’ standardized ophthalmology-specific EMR, which routinely collects very detailed data about patients. “This includes information on the status of diabetics, operative complications, and copathologies,” said lead author, Colin J. Chu, PhD, clinical lecturer in ophthalmology at the University of Bristol.

Analysis by risk strata. The large population and copious data allowed the researchers to sequentially isolate individual risk factors and to stratify patients into 3 groups. Patients who had received prophylactic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were excluded from the analysis.

Group 1 included 35,563 eyes of patients with no identified risk factors or diabetes at the time of surgery. PME was diagnosed in 415 eyes, yielding an incidence of 1.17%.

Group 2 patients had at least 1 risk factor but no diagnosis of diabetes at the time of surgery. PME was diagnosed in 178 of 11,429 eyes, for an incidence of 1.56%.

Group 3 included patients with diabetes at the time of surgery. PME was diagnosed in 181 of 4,485 eyes, an incidence of 4.04%. The number of patients allowed the researchers to analyze outcomes based on the presence or absence of diabetic retinopathy at time of surgery.

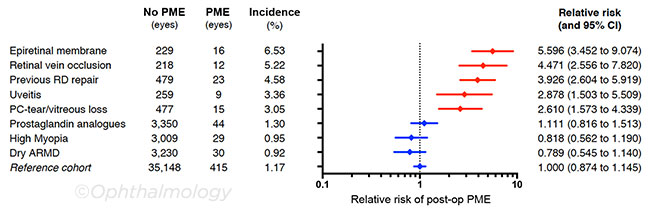

Relative risks of PME. As expected, said Dr. Chu, the presence of ocular comorbidities including epiretinal membrane, retinal vein occlusion, and uveitis was linked to a higher relative risk of PME, as were intraoperative complications such as posterior capsular rupture and vitreous loss (see graph below). Surprisingly, men were found to have a higher risk than women, a result that had not been seen in earlier studies.

Among the preselected conditions that were not found to increase PME risk are preoperative prostaglandin analogue use, high myopia, and dry age-related macular degeneration.

|

RELATIVE RISK FOR EYES FROM PATIENTS WITHOUT DIABETES with a single copathologic feature or risk factor. The mean relative risk compared with the reference cohort is plotted with 95% CIs. Because only a single risk factor was permitted, each diagnosis was mutually exclusive, so eyes were analyzed only once. Red indicates factors that were found to be statistically significant (p < .05). ARMD, age-related macular degeneration; PC, posterior capsule; RD, retinal detachment.

|

New data on diabetes. “Previous studies have made half-hearted attempts at examining links between diabetes and PME,” said Dr. Chu, “or they’ve excluded patients with diabetes due to challenges in determining whether the macular edema is caused by the surgery or the disease itself.”

In this study, however, patients had a preoperative structured assessment of diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy to generate a precise Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) grading. Sufficient data were available through the EMR, said Dr. Chu, to confidently exclude patients who had evidence of preoperative macular edema. “Once we excluded preexisting maculopathy, we saw a nearly linear increase in risk in PME with increases in the ETDRS severity of retinopathy.”

Don’t underestimate PME impact. Within the clinical community, said Dr. Chu, some have expressed a feeling that macular edema often “sorts itself out.” But that’s not what this study showed. Vision of patients in group 1, even those who received treatment for PME, including NSAID drops or intravitreal injections, did not catch up even by 24 weeks, he said.

“This suggests that prevention is likely better than treatment,” said Dr. Chu. By homing in on individual risk factors, this study can aid in counseling and monitoring patients and help to guide clinical approaches, such as the use of prophylactic NSAIDs, for those in high-risk groups.

—Annie Stuart

___________________________

1 Chu CJ et al. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(2):316-323.

___________________________

Relevant financial disclosures: Dr. Chu—None.

For full disclosures and disclosure key, see below.

More from this month’s News in Review