Download PDF

Charles Prince* was one of the most upstanding guys you could ever meet. The good-natured, hardworking 53-year-old had a lot on his plate—working a full-time job while caring for his mother, who has Alzheimer disease. He reported that, about 3 weeks earlier, he noticed that his right eye had become red after he lifted his mother. He visited his optometrist, who told him that he had a subconjunctival burst blood vessel.

The redness cleared but returned 2 weeks later. This time it was accompanied by swelling of the right eyelids, which worsened progressively until he couldn’t open that eye. He returned to the optometrist, who advised him to go to the nearest emergency department for further evaluation. At that time, Mr. Prince denied ocular pain, pain with eye movements, diplopia, changes in vision, recent trauma, or systemic illnesses, including sinus disease or fevers. He had no other notable medical or ocular history.

We Take a Look

Vital signs revealed that Mr. Prince was afebrile. Uncorrected visual acuity was 20/60 in the right eye and 20/50 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure was 21 mm Hg in the right eye and 11 mm Hg in the left. His pupils were equal, round, and reactive, with no afferent pupillary defect in either eye. Confrontation visual fields, which had to be performed with assistance to raise the right eyelid, were full in both eyes.

Mr. Prince’s eyes were straight in primary gaze. The right eye had limitations in all directions of gaze, while the left eye had full ocular movements. Color vision, as tested with Ishihara plates, was normal.

Further exam findings. The right eyelids were firm and edematous, but without erythema or tenderness to palpation. There was trace infraorbital ecchymosis.

Slit-lamp examination showed marked chemosis in the right eye that covered the superior half of the cornea. The remainder of the anterior segment examination, including the entirety of the left eye, was normal.

Funduscopic examination was remarkable only for a few macular drusen bilaterally.

Computed tomography. Maxillofacial CT scan with intravenous (IV) contrast showed diffuse thickening of the skin of the right eyelids, with abnormal contrast enhancement that extended into the orbit and surrounded the globe. The lateral rectus muscle was enlarged. There was no enhancing fluid collection to suggest an abscess, and no active inflammatory process was present in the paranasal sinuses.

Lab results. A complete blood count revealed a hemoglobin level of 9.7 g/dL (normal, 13.5-17.5 g/dL); there was no leukocytosis. Results of a comprehensive metabolic panel were within normal limits.

A Tumultuous Hospital Course

Given the extension of contrast enhancement into the orbit, Mr. Prince was admitted to the ophthalmology service with a presumptive diagnosis of orbital cellulitis. He was treated with IV antibiotics, topical erythromycin ophthalmic ointment, and oxymetazoline nasal spray.

Ruling out infection. Inflammatory etiologies were high on our differential diagnosis, but infection needed to be ruled out first. Blood cultures were drawn, and the infectious disease service was consulted.

Mr. Prince remained on IV antibiotics for 3 days, during which time he remained afebrile and pain free. He did not develop leukocytosis, and his blood cultures were negative for growth. However, his eyelid swelling progressively worsened.

Because of the patient’s lack of response to IV antibiotics, we revisited the diagnosis of orbital cellulitis. Orbital inflammatory disease moved to the top of the list of differential diagnoses, and we ordered blood work to evaluate for a possible associated systemic disorder.

Oculoplastics consult. We consulted with the oculoplastics service, which recommended magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate for an abscess before starting Mr. Prince on systemic corticosteroids. The MRI showed diffuse inflammation in the preseptal and postseptal tissues of the right orbit; marked thickening and edema of the lateral rectus muscle; and thickening, edema, and enhancement of the lacrimal gland (Fig. 1). There was no active inflammatory process in the paranasal sinuses and no subperiosteal fluid collection or abscess.

Mr. Prince was started on IV methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol), which he received for 3 days, but the eyelid swelling continued to progress.

Suspicion of malignancy. As the patient’s eyelid swelling did not respond to antibiotics or corticosteroids, malignancy rose to the top of our differential. An initial chest x-ray showed soft tissue prominences in the right peritracheal region, right apical region, and right superior mediastinum.

|

|

MRI. Magnetic resonance imaging shows diffuse inflammation in preseptal and postseptal tissues of the right orbit with thickening of the right lateral rectus muscle.

|

An Unexpected Call

In the middle of a hectic clinic, the resident received a call from the floor that Mr. Prince was vomiting bright red blood. The patient was transferred to the medicine service, the gastrointestinal service was consulted, and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was scheduled for the next day.

As part of the malignancy workup, he also underwent CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. These scans showed evidence of bilateral pulmonary emboli; retroperitoneal nodularity and infiltrative tissue that raised concern for lymphoma or another neoplasm; nodular, plaque-like bladder wall thickening; and generalized gastric and focal colonic wall thickening.

EGD revealed 3 ulcers, diffuse edema, and friable tissue throughout the stomach that was strongly suspicious for malignancy. Gastric biopsies were performed, and the eyelid and lacrimal gland were biopsied the following day.

Final Diagnosis

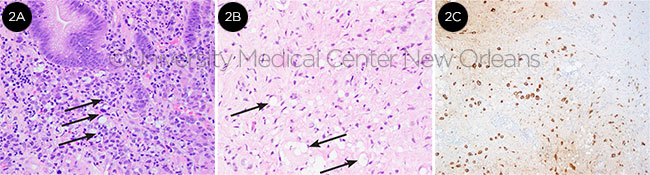

The gastric biopsies revealed invasive poorly differentiated signet ring cell carcinoma. The eyelid biopsies showed poorly differentiated carcinoma, and the lacrimal gland biopsies were suspicious for carcinoma (Fig. 2). Mr. Prince’s final diagnosis was signet ring cell gastric carcinoma with widespread metastases, including to the right orbit and eyelids.

|

|

HISTOPATHOLOGY. Images from the (2A) gastric biopsy showing signet ring cells, (2B) right eyelid showing poorly differentiated carcinoma with occasional signet cells, and (2C) immunohistochemical staining of the right eyelid tissue, which was positive for pancytokeratin and negative for CD45, CD3, CD20, and S100. Pancytokeratin is found in epithelial cells. The presence of diffuse staining in the biopsy is suggestive of neoplasia.

|

Discussion

Orbital metastases. Metastatic involvement of the orbit is uncommon. Orbital metastases occur in 0.07% to 4.7% of patients with malignancies1 and account for 2% of orbital tumors.2 Common sites of involvement are the extraocular muscles (because of their rich blood supply) and the bone marrow space of the sphenoid bone (because of its relatively high volume of low-flow blood).3

Orbital symptoms and signs, such as pain, proptosis, and ophthalmoplegia, are common. Other signs include blepharoptosis, a palpable mass, blurred vision, and diplopia.4 The most frequent sources of orbital metastases are the lung, breast, and prostate4; gastrointestinal metastases are rare, accounting for approximately 2% of orbital metastases in an Italian study.5 The presence of orbital metastases is a poor prognostic sign, with an average survival time of 13.5 months after the diagnosis of orbital metastasis.5

Eyelid metastases. Eyelid metastases are even rarer, representing 1% of malignant eyelid lesions.6 There are 3 main patterns of eyelid metastases: nodular, ulcerated, and diffuse. Nodular metastases appear as elevated skin-colored lesions that are sometimes mistaken for chalazia. Ulcerated lesions occur when the malignant cells involve the epidermis. Diffuse lesions present as firm, painless swelling of the periocular skin; they are easily mistaken for contact dermatitis or orbital cellulitis, as in Mr. Prince’s case.

Back to Our Patient

At his 1-month oculoplastics follow-up, Mr. Prince was in good spirits and pain free. His ocular examination was stable, but his visual acuity had decreased to 20/80. Debulking surgery was deferred because he had no evidence of exposure keratopathy or optic nerve compression. He was scheduled to start radiation treatment the next day. Mr. Prince continued palliative radiation treatments but declined palliative chemotherapy.

Over the next several months, he returned 9 times for either gastrointestinal bleeding or shortness of breath from malignant pleural effusions. Four months after his initial presentation, he was admitted to the hospital for profound gastrointestinal bleeding, with a hemoglobin of 5.0 g/dL that required several blood transfusions.

Once stabilized, he underwent EGD, which showed diffuse nodularity of the body, fundus, and antrum of the stomach. There were no discrete lesions that could be cauterized or ligated. Mr. Prince continued to have hematemesis, melena, and hematochezia. After an extensive discussion with his physicians and family, he decided to transition to comfort care. He passed away the next day.

___________________________

*Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Souyah N et al. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28(3):240-241.

2 Ahmad SM et al. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18(5):405-413.

3 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 7, Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System. 2017-2018.

4 Shields JA et al. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17(5):346-354.

5 Magliozzi P et al. Int J Ophthalmol. 2015;8(5):1018-1023.

6 Hee Won K et al. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27(4):439-441.

___________________________

Dr. Lao is a second-year ophthalmology resident at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans. Dr. Sahu is an oculoplastics specialist at Ochsner Medical Center, New Orleans, and assistant professor of ophthalmology at University of Queensland-Ochsner School of Medicine. Dr. Barron is a cornea specialist and clinical professor of ophthalmology at LSU Health Sciences Center, New Orleans. Financial disclosures: Dr. Barron: Barron Precision Instruments: O.

See the disclosure key at www.aao.org/eyenet/disclosures.