This article is from February 2012 and may contain outdated material.

Hope. Low vision specialists offer their patients not drugs or surgery but the hope that, after exhausting all medical interventions, they will still be able to perform activities of daily living with the help of compensatory techniques and devices. Today, some of these devices are as close at hand as the nearest consumer electronics store. “The boundaries between what would be good for the general population and the low vision population have merged,” said Janet S. Sunness, MD, medical director of Richard E. Hoover Rehabilitation Services for Low Vision and Blindness, at the Greater Baltimore Medical Center. “These things are not science fiction; they’re not so expensive or impossible to obtain. They just need to be adapted so they’ll work for people with low vision.”

Dr. Sunness was referring to the electronic devices that many people buy for convenience and cool: smartphones, e-readers and tablet computers. In the hands of the visually impaired, these devices improve quality of life and foster independence.

Can Consumer Electronics Replace Dedicated Devices?

“While a lot of these [consumer electronics] appeal to the masses and are wonderful in general, they can also be applied to medicine and ophthalmology,” said John W. Kitchens, MD, a retina specialist at Retina Associates of Kentucky, in Lexington.

Dedicated devices may lose ground. Ronald A. Schuchard, PhD, predicted that the use of consumer electronic products will eventually overtake the niche market for dedicated low vision devices, such as closed-circuit TV magnifiers (CCTV). “The CCTV world is going to become much less necessary,” said Dr. Schuchard, a scientist at VA Palo Alto Rehabilitation R&D Service and clinical associate professor of neurosurgery at Stanford University. “We’re not quite there yet, but it’s getting to the point of, ‘Why buy a $2,000 or $3,000 CCTV, if you can have a $500 iPad?’”

Mobile devices may allow earlier visual rehabilitation. Mary Lou Jackson, MD, director of vision rehabilitation at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, agreed. “People don’t always have to get some niche device,” she said. “They can actually use their own cell phone or computer with accessibility features.” She added that these products are helping to debunk the myth that you have to wait until a patient has very limited vision before offering vision rehabilitation tools. Today, with the array of general consumer devices that double as low vision aids, there’s no excuse not to start sooner rather than later.

But consumer devices don’t meet all needs. Susan Garber, OTR/L, CLVT, a low vision occupational therapist in Dr. Sunness’ office, said that although these smart devices can be lifesavers, they don’t eliminate the need for dedicated niche products. “If you have an iPad, you’ll probably still need some other kind of aid to get you through your daily routine,” she said. For example, tablets and e-readers have limitations in terms of contrast settings and magnification, whereas some specialized CCTVs can project images of pill bottles, mail and recipes onto a screen at up to 85 times magnification. “If you have goals of being able to cook, manage your checkbook and manage your medications, the iPad isn’t going to achieve them.”

Expert help still required. Ms. Garber also said that even the smartest devices don’t eliminate the need for a vision rehabilitation specialist. Although she sends patients to the big box electronics stores to sample what’s available, she said that patients still need a specialist to help tailor the devices to their particular visual needs and provide training in how to use them effectively.

Dr. Schuchard, who is conducting a study of e-readers and other home electronics devices for people with central vision loss, agreed. “It can be a challenge for people to use these,” he said. “You don’t just go to an Apple store, buy a smart device and start using it. My concern is that a person with low vision will buy it, try to use it and get frustrated.”

|

|

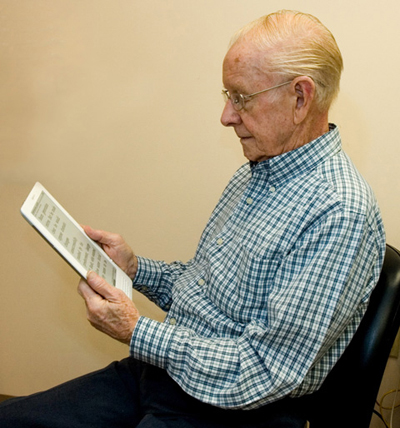

This patient is using an e-reader that allows him to alter the text size and contrast level on the screen.

|

Smart Device Capabilities

Although the consumer electronic devices are not perfect, the experts agree that people with low vision should explore what’s available. Here’s a look at some of the most widely used items.

E-readers. Portability is one of the biggest advantages of these devices. Reading can take place anywhere, not just at a desk. E-readers allow the user to change the font size, font style and contrast of the display. In addition to enabling users to alter visual display parameters, the Kindle and iPad have text-to-speech options. But one size doesn’t fit all, said Dr. Schuchard.

Choosing an e-reader. In a pilot study supported by the American Foun- dation for the Blind, Dr. Schuchard found that an individual’s contrast sensitivity determines the degree of difficulty in reading the displays.

Dr. Schuchard suggested the following guidelines when advising patients about e-readers:

- Be sure that the contrast of the display accommodates the individual’s contrast abilities. This decision is affected by whether the e-reader will be used indoors or out.

- Suggest that patients try out reversed- polarity (i.e., white letters on black background) as well as standard displays. Such reversal is available on devices that emit their own light, including the iPad, but not those that use available light, such as the Kindle. This capability may benefit patients who are particularly sensitive to glare.

- Consider screen size, especially if the patient has very poor visual acuity and is not planning to use an additional magnifier.

- Evaluate goals. If the patient’s goal is only to read books, avoid a device with confusing bells and whistles.

Smartphones and tablets. Apple’s iPhone and iPad support an array of low vision apps, but Google-based Android, BlackBerry and Windows platforms have also “gotten into the app world,” Dr. Schuchard said.

Voice interface on iPhone. Still, it’s the iPhone that most of the experts mention when discussing these devices. “The iPhone does so much. It’s almost in a class by itself,” Dr. Jackson said, referring particularly to the 4S model that includes Siri, a program that responds to voice commands and even talks back. “To have that voice interface is quite revolutionary. I’m already showing it to patients,” she said.

Data from an iPad study. Smart tablets roll many functions into one, including acting as e-readers. Researchers at the University of Florida, in Jacksonville, assessed the effect of iPad use on reading ability and quality of life in 144 patients with BCVA worse than 20/200. Patients were encouraged to enlarge the text until they could read comfortably. Among these patients, 9 out of 10 had improved reading ability using the iPad compared with using only their spectacles. The iPad also improved patients’ quality of life, as demonstrated by results of a modified VF-14 questionnaire.1

Ms. Garber’s anecdotal experience supports such findings. “People with low vision have many of the activities of daily living stripped away from them. Then, suddenly, with an iPad, they’re playing games,” she said. “You’d be surprised at how many people over 80 are willing to use an iPad,” she added. “Their quality of life is enhanced in a way you’d never think imaginable. All they have to do is tap on the app.”

Apps for Patients and Doctors

The world of apps is continually expanding for both Apple and Android platform products.

iRead app. This free, handheld magnifier app was developed by ophthalmologist Richard G. Davis, MD, of Long Island, N.Y., for both the iPhone and Android platforms. It uses the phone’s camera and LED light source to magnify and illuminate text. Many other light/magnification apps are also available, including Tap Magnify, Magnify, iLoupeOne, iLoupe, iCan See, and iMagnify.

Ms. Garber has reservations about the ability of phone apps to replace a magnifier. “If you only need magnification of up to four times, the apps would probably work,” she said, but patients with higher needs are better off using handheld magnifiers with powers up to 14 times. Of course, efficient use of either handheld magnifiers or smartphones requires steady hands.

The EyeNote app. This free application for Apple products was developed by the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing to help visually impaired people use paper money. The smart device scans the bank note and tells the user its value by reading aloud or using pulsed vibrations.

SightBook app—for patients and Eye M.D.s. Dr. Kitchens called SightBook a novel tool that allows patients to track their vision and share that information with their ophthalmologist. SightBook contains a set of quantitative near vision tests, which an individual can take using an Internet-connected mobile device. The tests, which have been correlated with traditional measures of visual function, include Snellen visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, color discrimination and Amsler grid. Patients don’t always recognize changes in their vision, and doctors sometimes defer treatment, said Dr. Kitchens. But with SightBook, “Patients monitor their vision, and the app will notify us of any change in vision.” The SightBook app is free with an iTunes account. For more information, visit www.digisight.net.

What’s Next?

In the last two to three years, the market for consumer electronic devices and their applications has exploded, said Dr. Schuchard. Which device is best for people with low vision? “The answer to that question is very individualistic,” he said.

Dr. Jackson said it’s impossible to single out a device. “As they keep leapfrogging each other, one company is the best portable, then six months later there’s something new. In general, most of the major players have comparable devices,” she said. “If money’s not an object, a person would get one device to sit on the desk and one to hold in the hand.”

In the meantime, Dr. Schuchard is looking forward to studying the voice interface function. “We’re all waiting to jump on that bandwagon to see how much a person with visual function problems will love Siri.”

___________________________

1 Chalam KV et al. Evaluation of the Impact of the iPad (as a Low Visual Aid) on Reading Ability and Quality of Life of Low Vision Patients. Poster presented at Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology; October 21-23, 2011; Orlando, Fla.

___________________________

Dr. Jackson receives grant support from Optelec USA. Ms. Garber and Drs. Kitchens, Shuchard andSunness report no related financial interests.

SmartSight Resources

“The ophthalmologist has a professional role and an ethical responsibility to say to a patient with any decreased function, ‘There are things out there that can help,’” said Dr. Jackson, who chairs the Academy’s Vision Rehabilitation Committee. The Academy’s SmartSight initiative, launched to help patients make the most of remaining vision, helps doctors and patients identify useful tools and services. Dr. Jackson encouraged ophthalmologists to print out the patient information materials available at SmartSight. They include tips on computers and video magnifiers and information on effective use of vision. The site also directs patients to a state-by-state listing of community resources. For more information, visit www.aao.org/smartsight.

|