By Elaine A. Richman, PhD, Contributing Writer

Interviewing Glenn Cockerham, MD, Col. (Ret.) Donald A. Gagliano, MD, MHA, Randy Kardon, MD, PhD, and Robert A. Mazzoli, MD

Download PDF

Combat operations over the last decade in Iraq and Afghanistan have taught physicians many lessons about traumatic brain injury; one of the most salient to ophthalmologists is the recognition that even mild TBI (mTBI), also known as concussion, can cause visual problems.

Between 2000 and the third quarter of 2013, an estimated 287,861 service members sustained a TBI,1 most of which were classified as mTBI. A substantial proportion of patients—74 percent in one study—experienced visual problems associated with TBI.2

The topic of TBIs is relevant to community, as well as military, ophthalmologists because service members and veterans are often treated by physicians outside the Military Health System and Veterans Health Administration. Beyond that, mTBI is a growing public health concern in the civilian milieu. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that in 2009 TBI was responsible for at least 2.4 million emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or deaths (excluding military or nonhospital settings). Most were mild and related to sports, motor vehicle accidents, falls, or fights.3

Diagnosing mTBI-related visual impairment requires awareness of the problem and, sometimes, special assessment protocols and tools. Here is some guidance from ophthalmologists who gained experience in military and VA settings.

|

Retinal Effects of TBI

|

|

|

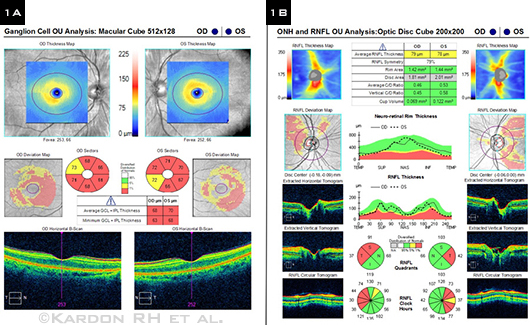

Recent research found that veterans with TBI had a higher rate of retinal thinning than did a control group. Thinning was more pronounced in the ganglion cell layer (1A) than in the retinal nerve fiber layer (1B), as seen in this patient.

|

A Tricky Diagnosis

“Diagnosis of an mTBI-related visual impairment is complicated,” said Col. (Ret.) Donald A. Gagliano, MD, MHA, at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md. “For one, symptoms can take time to manifest, creating a delay in diagnosis.” By the time patients see an eye doctor for care, they are usually frustrated and worried. “They are concerned about their eyesight and anxious to get back to their jobs and families and lead a normal life.”

“Normal” exams. A routine ophthalmic exam typically looks normal in patients with TBI, said Randy Kardon, MD, PhD, at the University of Iowa and the Iowa City VA Center. Yet patients commonly report problems including blurred vision, squinting, light sensitivity, double vision, and difficulty reading, watching television, and using computers. Thus, “We need reliable tests, biomarkers if you will, to assess visual dysfunction within a time frame that’s useful to these men and women. Most have been told that their eyes look fine, but they know they are having trouble seeing. Visual acuity might be 20/20, but they’re struggling and want help,” he said.

Denial or forgetfulness. A further impediment to diagnosis of mTBI-related visual dysfunction is that many service members deny that they’ve had a concussive injury, even though they’ve been exposed to a blast or blasts. And their military records might not help. “Soldiers tend to associate concussion with losing consciousness,” said Dr. Gagliano, “so they don’t necessarily report it to medical personnel.”

Visual Effects of mTBI

mTBI-related visual symptoms differ from patient to patient. The cause of an injury (e.g., blunt force, blast, other head trauma), direction or intensity of force, part of the visual system affected, and patient-specific conditions (such as earlier head injury or genetic predisposition) may make for a better or worse outcome.4 “These patients are a heterogeneous group,” said Dr. Gagliano.

Light sensitivity. “Severe photophobia is especially common, sometimes with headache and migraine,” said Dr. Kardon. “About 60 percent of veterans who have had a TBI self-report extreme sensitivity to light. In fact, it’s the most common visual complaint. Even in the waiting room they wear sunglasses.”

Other visual problems. In a recent article, neuro-ophthalmologist Eric L. Singman, MD, PhD, reported on visual dysfunctions in TBI and methods for assessing them.5 In addition to glare and photophobia, he listed the following problems:

- Loss of visual acuity, color discrimination, brightness detection, and contrast sensitivity

- Visual field defects

- Visuospatial attention deficits; slower response to visual cues

- Visual midline shift syndrome, affecting balance and posture

- Impaired accommodation and convergence

- Nystagmus

- Visual pursuit disorders

- Deficits in the saccadic system

- Extraocular motility problems resulting in strabismus, diplopia, or blurred vision

- Reduction in stereopsis

- Reading problems, including losing one’s place, skipping lines, and slow reading speed

Ongoing Research Projects

Because light sensitivity is commonly associated with mTBI, Dr. Kardon and colleagues are researching objective measures to characterize photophobia in these patients. The researchers are using the pupil light reflex to study photoreceptor- and melanopsin-mediated pupil responses and electromyogram recordings from orbicularis and procerus muscles to study the nervous system’s response to light.

In other research, Glenn Cockerham, MD, at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System, and Dr. Kardon are using optical coherence tomography to track anatomic changes in the visual system following blast injury. “We’re seeing a thinning over time of the inner retinal layer and in the optic nerve,” said Dr. Cockerham.1 Thinning is most pronounced in the ganglion cell layer (Fig. 1). “As in multiple sclerosis, we might be able to use the retina to monitor TBI progression.”

“Further, by studying the pathophysiology of TBI and related vision problems,” added Robert A. Mazzoli, MD, of Tacoma, Wash., a specialist in blast injuries to the eye, “we hope to find ways to prevent them. Researchers are looking at possible neuroprotective approaches to TBI.” He referred to recently published research in rodents showing that acute brain injury induces an inflammatory response in the brain that is modified by the administration of the antioxidant glutathione.2

___________________________

1 Kardon R et al. Prevalence of structural abnormalities of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell layer complex (GCLC) by OCT in veterans with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54: E-Abstract 2360.

2 Roth TL et al. Nature. 2013. doi: 10.1038/nature12808. |

Assessing the TBI Patient’s Vision

When working with veterans in particular, Dr. Kardon emphasizes the importance of taking time with them, thanking them for their service, and listening carefully to their symptoms and for clues about their exposure to blasts. “Some of these patients have posttraumatic stress disorder. Most are stoic. All are looking for a solution.”

Guidelines for screening. Vision experts at the VA recently published mTBI vision-screening guidelines for eye care providers to use as an adjunct to a conventional eye exam.6

Important tests and questions for all TBI patients. The guidelines identify the following exams as being important for every TBI patient: distance cover test, near cover test, versions (extraocular motility) and pursuit, accommodation, saccades, near point of convergence, and repeated near point of convergence.

In addition, the guidelines present a list of questions to ask the patient; they are designed to elicit information in six categories related to history of the TBI event, sensory effects, eye injury/pain, vision, and reading.

Red flag/yellow flag symptoms. Similarly, the Military Health System’s Defense Centers of Excellence has developed recommendations for mTBI vision screening, based on expert opinion from Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, and Navy representatives.4

These recommendations, including an assessment algorithm, are intended for use by primary care physicians in the theater of war and elsewhere as a guide to identifying eye problems that require urgent referral to a specialist (red flags) versus common visual symptoms following concussion (yellow flags). The algorithm includes procedural recommendations for screening and referral processes to help determine whether to refer a particular patient to ophthalmology, neuro-ophthalmology, optometry, neurology, or maxillofacial surgery. (See the Web Extra below for a list of the red and yellow flags, as well as suggested assessment questions and tests.)

Helping the TBI Patient

Just as every case of mTBI is different, so, too, is the course of the visual symptoms. They can be as brief as minutes or persist for days, weeks, months, or more. With proper diagnosis and management, most patients with mTBI recover fully,7,8 often within three months.4 But in a minority of cases, symptoms are persistent, and patients may need help managing a return to their maximum capacity.

Photophobia is sometimes helped by special sunglasses or contact lenses that limit the amount of light entering the eye. Optical aids can help resolve double vision or accommodative focusing problems. Headaches that persist might need the intervention of a neurologist. “You’ll find the vision specialists in the VA facilities especially prepared to work with these patients,” said Dr. Kardon.

“I usually recommend to patients that they take it easy for a while. I mean cognitively and physically,” said Dr. Cockerham. “Most need help understanding their visual problem and the limits the changes might impose in the long and short term. This allows them to plan their return to work, school, sports, and family responsibilities. They’re not the only ones who are affected. So are their families, employers, and friends. Our help goes a long way to reducing anxiety and improving overall quality of life.”

___________________________

1 DoD worldwide numbers for TBI. Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center.

2 Goodrich GL et al. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(7):929-936.

3 CDC Grand Rounds: Reducing severe traumatic brain injury in the United States. July 12, 2013.

4 Defense Centers of Excellence. Assessment and management of visual dysfunction associated with mild traumatic brain injury. DCoE Clinical Recommendation. January 2013.

5 Singman EL. Med Instrum. 2013. doi: 10.7243/2052-6962-1-3.

6 Goodrich GL et al. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):757-768.

7 Kushner DS. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(15):1617-1624.

8 Alexander MP. Neurology. 1995;45:1253-1260.

___________________________

Glenn Cockerham, MD, is the National Program Director for VA Ophthalmology Services, at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System. Financial disclosure: None.

Donald A. Gagliano, MD, MHA, is a retina specialist at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and assistant clinical professor at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. Financial disclosure: None.

Randy Kardon, MD, PhD, is the Director of Neuro-ophthalmology Services at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine and Director of the Iowa City VA Center of Excellence for Prevention and Treatment of Visual Loss. Financial disclosure: Is a consultant for Novartis and Zeiss Meditec.

Robert A. Mazzoli, MD, is former Consultant to the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army and former chief of ophthalmology at Madigan Army Medical Center in Tacoma, Wash. Financial disclosure: None.