By Vladimir S. Yakopson, MD, Eric D. Weber, MD, and Richard H. Birdsong, MD

Edited by Thomas A. Oetting, MD

This article is from July/August 2009 and may contain outdated material.

Jorge Rodriguez* is an active 8-year-old boy who had been enjoying life on a Caribbean island. One day, however, during a school screening exam, he was noted to have poor visual acuity in one eye. He was urgently referred to a local ophthalmologist who recorded an uncorrected visual acuity of 20/200 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left. The doctor also described a “small delay in reaction to direct light” but no afferent pupillary defect. Mild elevation and blurring of borders of the right optic nerve head were also described, with the rest of the exam being normal. The doctor was concerned about the possibility of optic neuritis and sent the patient to an emergency room to receive intravenous steroids. Jorge is the son of U.S. military personnel who are assigned to the local embassy, and the next morning he was flown with his mother stateside for an urgent neuro-ophthalmology consultation by us.

We Get a Look

According to the mother, the child had one prior eye check three years earlier at his pediatrician’s office in the United States. No abnormalities were noted at that time. Jorge had never complained of any visual difficulties. He had no recent eye or periorbital pain, discharge, redness, irritation or photophobia. The mother had never noticed any strabismus, nystagmus or unusual head posture. Medical history was noncontributory. There was no family history of multiple sclerosis or eye disease.

On our exam, Jorge’s vision was 20/100 +1 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left, with stereoacuity of 100 seconds of arc. At our facility, Jorge was examined by a senior resident, a pediatric ophthalmologist and a neuro-ophthalmologist. Only one of these three physicians could detect a trace afferent pupillary defect in the affected eye. Anterior segment and IOP measurements were within normal limits. Extraocular motility was full, and the patient was orthophoric on muscle balance. Automated static perimetry testing revealed generalized depression in the affected eye and a normal visual field in the unaffected eye.

A cycloplegic refraction was performed. The refraction was as follows: +3.00 +1.50 x 090 in the right eye (improving visual acuity by one line to 20/80) and +1.00 sphere in the left. It revealed mild hyperopia in one eye and moderate hyperopia with astigmatism in the affected eye. Both the 2 D of spherical difference as well as the 1.5 D of cylindrical anisometropia are amblyogenic.1 This could explain Jorge’s poor vision in the right eye.

What About the Optic Neuritis?

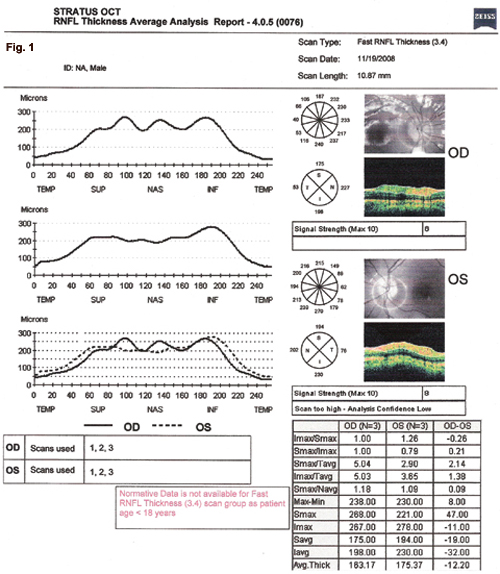

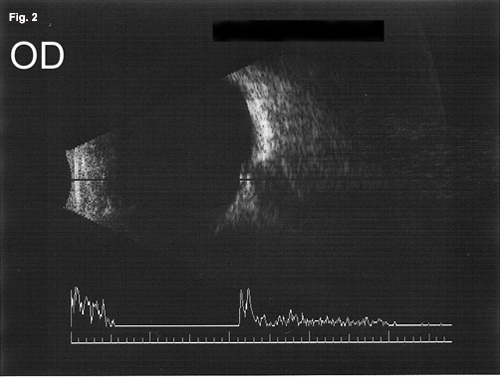

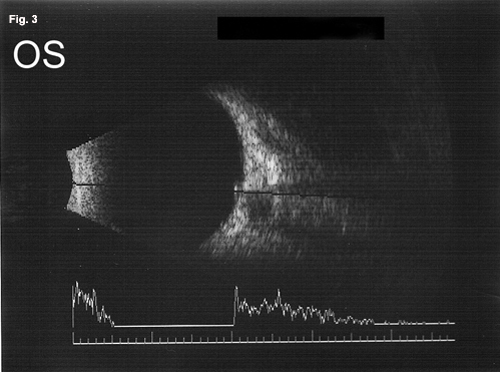

On dilated fundus exam, the optic nerve heads appeared small and somewhat elevated in both eyes. The margins were sharp, and there were no exudates or hemorrhages. The posterior poles were unremarkable. Retinal nerve fiber layer optical coherence tomography (RNFL OCT) demonstrated symmetric thickening of the RNFL in both eyes (Fig. 1). B-scan ultrasound confirmed the presence of hyperechoic areas within the optic nerve heads (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). We made a second diagnosis of optic nerve head drusen causing bilateral pseudopapilledema.

|

|

RNFL OCT. We noted symmetric RNFL thickening in both eyes. In fact, the average RNFL thickness in the left eye is slightly higher than in the right (Fig. 1).

|

Therapeutic Plan

Because there were no other neurologic signs and the refractive error was amblyogenic, neuroimaging did not seem warranted. We prescribed the full cycloplegic refraction, recommending full-time spectacle wear, as well as patching of the left eye for four to six hours per day. We recommended follow-up in three to four months.

|

|

|

B-Scan Ultrasonography. We noted the presence of optic nerve head drusen in both eyes (Figs. 2 and 3).

|

Discussion

As physicians, we are well-trained to apply the principle of Occam’s razor in our diagnostic workup. We try to find a unifying diagnosis to explain all the presenting symptoms and signs. However, a sometimes overlooked corollary is Hickam’s dictum: “Patients can have as many diseases as they damn well please.” In our patient’s case, we believe that the child has two separate unrelated diagnoses: refractive amblyopia and optic nerve head drusen.

Perform a thorough eye exam. In cases like this, a complete eye exam can avert confusion later on.

Differentiate papilledema from pseudopapilledema. Pseudopapilledema due to optic nerve head drusen can serve as a red herring. Important differentiating features indicating true optic disc edema include blurring of the optic disc margin, obscuration of retinal vessels, peripapillary hemorrhages and exudates, retinal or choroidal folds, hyperemia and dilation of optic disc surface capillary net. While OCT confirmed that Jorge’s discs were elevated, none of the other signs were present. B-scan ultrasonography is currently the best way to diagnose optic nerve drusen. Recently, OCT criteria for differentiating true papilledema from pseudopapilledema were proposed.2 However, our patient encounter took place before the article was published so we weren’t able to apply those criteria.

Consider the RNFL. In Jorge’s case, RNFL OCT showed symmetric bilateral thickening of the RNFL. This helped move us away from a differential diagnosis involving significantly asymmetric presentation. Our OCT printout noted the absence of normative data for children, but in a recent study, researchers gathered such data for children aged 3 to 17 and found that the average RNFL thickness was 108 µm. The study’s authors also reviewed past studies, including adults and children, which show a range of normal RNFL thickness from 94 to 115 µm.3

Tools to help seal the diagnosis. In addition to the retinoscope, most comprehensive practices involved in cataract surgery have tools that can measure axial length and corneal curvature. Even if a dedicated B-scan is not available, many of the ophthalmic ultrasound units have built-in A- and B-scan capabilities. We used a B-scan to confirm that Jorge had optic nerve head drusen. An axial length measurement can also confirm the degree of anisometropia noted by retinoscopy (not performed in this case).

Without careful monocular screening, amblyopia may go undetected. How can a child hide an eye that is 20/100? Even if a child is told to cover one eye, he or she may cover the bad eye first, and then repeat the same line while “looking” with the bad eye.

Summary

Amblyopia may present at a relatively late age if careful screening has not been performed. Children with amblyopia may have other, unrelated ocular findings, which may confound the examiner. Therefore, cycloplegic refractions must be part of every pediatric eye exam, especially when visual acuity is decreased. Readily available instruments may obviate the need for a more extensive workup.

___________________________

* Patient name is fictitious.

___________________________

1 Miller, J. M. and E. M. Harvey. J. Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1998;35:50–52.

2 Johnson, L. N. Arch Ophthalmology 2009;127:45–49.

3 El-Dairi, M. et al. Arch Ophthalmology 2009;127:50–58.

___________________________

Capt. Yakopson is a third-year resident, Maj. Weber is a neuro-ophthalmologist and Col. Birdsong is a pediatric ophthalmologist. All are at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

___________________________

PLEASE NOTE: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Army, Department of Defense or U.S. government.