During my second year of ophthalmology residency (1967-68) at Washington University in St. Louis, I was working on a paper and needed a reference for some research I was doing.

During my second year of ophthalmology residency (1967-68) at Washington University in St. Louis, I was working on a paper and needed a reference for some research I was doing.

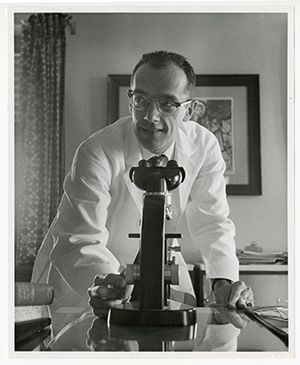

Prior to PubMed, one had to go to the library and manually search the literature. I asked Bernard Becker, MD, the chair of the department and my mentor for any leads, “George,” he said, “I think it is in the Archives of Ophthalmology (Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology) April or May 1957.” I returned to the library and there it was! He had also said it was written in German; it indeed was in German. His knowledge was encyclopedic, and his memory photographic.

By the age of 3, Bernard Becker could read and do math – long division and multiplication in his head. He was astonished the other children could not do the same. He was so far advanced in elementary school that he received a double promotion in grade, and from that point he was always the youngest in his class, but still ranked No. 1 academically in high school, university, medical school and residency.

At the age of 17, Dr. Becker entered Princeton University on a full tuition scholarship, but lacking money for food and books, he tutored fellow students to earn the necessary money.

Albert Einstein asked him to tutor his nephew. After Princeton, Dr. Becker attended Harvard Medical School and, for residency, Johns Hopkins Wilmer Institute. At the end of his third year of residency, he married Janet, who remained his wife for 63 years, until his death. He was interested in biochemistry and research, but he also served in the US Army as a psychiatrist.

Albert Einstein asked him to tutor his nephew. After Princeton, Dr. Becker attended Harvard Medical School and, for residency, Johns Hopkins Wilmer Institute. At the end of his third year of residency, he married Janet, who remained his wife for 63 years, until his death. He was interested in biochemistry and research, but he also served in the US Army as a psychiatrist.

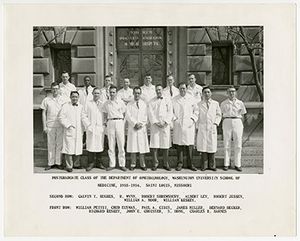

Dr. Becker loved old eye books. His collection of antiquarian ophthalmology books would later become the basis of the rare book collection at Washington University Becker library, one of the outstanding collections of its kind. In 1953 he was recruited as full-time chair of the department of ophthalmology, becoming the youngest chair at Washington University School of Medicine. When he joined the department, there was no formal residency training. The residents were required to read Duke-Elder's textbook and examine the patients primarily with a pen light.

Dr. Becker faced many challenges in building the department but overcame them to make it one of the finest in the country. Many of his students, residents and junior faculty are in leadership positions nationally.

Dr. Becker ran a tight daily schedule. In the morning he would read. He enjoyed his daily iced coffee and loved to swim in his home’s indoor pool, then come to the department in the afternoon and do administrative work. Friday afternoon eye rounds were a delight. He was able to get to the center of a clinical problem by asking the correct question, simultaneously making a teaching point. He also enjoyed playing poker with the staff. He could remember which cards had been played and calculate probabilities on the spot and was known to win big at these games. It was reported he read 100 journals a month. Once he read in a poultry industrial journal that chickens raised in the dark developed glaucoma and tried to use this as an animal model, but unsuccessfully. He developed techniques for diagnosing glaucoma and measuring rates of aqueous humor.

Dr. Becker and his wife were community leaders in integration and housing for the poor. At that time, there were wards that housed black and white people separately at the hospital. He was instrumental in making a black ward air-conditioned. Soon many patients in the white ward wanted to be admitted to the black ward in the hot summers in St. Louis.

Dr. Becker encouraged residents to do research in addition to clinical work. He helped establish the Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology, Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, Research to Prevent Blindness and the American Board of Ophthalmology. Dr. Becker and his wife were also generous benefactors to philanthropic organizations.

I would visit at his office or home after he retired. I asked him one day, what would he answer if one of his children asked what principle or rule to live by? I often ask this question and most respond with the “golden rule.” Dr. Becker said “to give” – one of the principles of Judaism. I also asked him about the source of his philanthropic funding. It was his private investments, picking the right stocks and bonds based on his reading of articles and of the mood of the country’s economy. I asked him yet another time: How to do you measure success in life? “You can tell your success in life by your offspring."

I would visit at his office or home after he retired. I asked him one day, what would he answer if one of his children asked what principle or rule to live by? I often ask this question and most respond with the “golden rule.” Dr. Becker said “to give” – one of the principles of Judaism. I also asked him about the source of his philanthropic funding. It was his private investments, picking the right stocks and bonds based on his reading of articles and of the mood of the country’s economy. I asked him yet another time: How to do you measure success in life? “You can tell your success in life by your offspring."

The oral history of Bernard Becker, MD is available at http://beckerexhibits.wustl.edu/oral/transcripts/becker.html