Donald “Don” M. Gass, MD, is one of the most influential ophthalmologists of the 20th century.

Dr. Gass was born on Aug. 2, 1928 on Prince Edward Island, Canada to a physician father and an attorney mother. His father was the head of tuberculosis hospitals in Tennessee at that time. He rode a train with his mother at age of 2 weeks to Nashville, where he grew up and attended the two-room Grassland primary school. It housed three grades in each room.

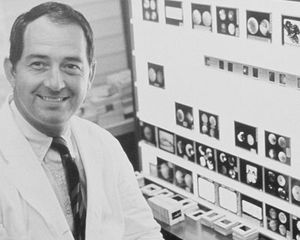

J. Donald M. Gass, MD, pictured with his slides on the view box.

He credits his love for reading and learning to a primary school teacher who used to fill her station wagon with books from the library each week so that the students could read them. Since three grades of lessons were taught in the same classroom, Dr. Gass was easily proficient in the higher-grade lessons that left him a lot of time to read and learn outside his schoolwork. This was the foundation for his super abilities.

Dr. Gass met Margy Ann Loser, his high school sweetheart, on the school bus. She was his first date and only love, and they were married in 1950. Dr. Gass attended Vanderbilt University for his undergraduate education. His plan was to enroll in engineering school at Vanderbilt, and when he arrived for admission, there was a shorter line for arts and science. If the engineering line was shorter, we may have only known him from a distance as a brilliant engineer. He graduated with high honors in 1950 and soon after was enlisted in the Navy and served in the Korean war.

On his return from the war, Dr. Gass and his wife lived for a short while in San Diego, Calif., where their first child John was born. Finishing his tenure in the Navy, he entered medical school at Vanderbilt and graduated with the highest honor, the founder’s medal. Dr. Anderson Spickard, his medical school classmate and professor of internal medicine at Vanderbilt recalls, Dr. Gass had the best notes in their medical school class, and everyone wanted to borrow them. Their second son Carlton was born in Nashville while Dr. Gass was in medical school.

Dr. Gass completed an internship at the University of Iowa and moved to Johns Hopkins for his ophthalmology residency. Media, their daughter, was born during his time in Baltimore.

Pictured left to right: Drs. Alan Bird, Don Gass and Pierre Amalric reviewing a fluorescein film, 1968.

At Johns Hopkins, he idolized Frank Walsh, MD the most distinguished neuro-ophthalmologist of the time. As a resident, Dr. Gass wrote many papers, ranging from corneal iron lines to Waardenburg’s syndrome. He was chosen chief resident at Johns Hopkins and completed an ocular pathology fellowship at Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP), between his residency and chief residency.

This ocular pathology fellowship was the perfect blend to young Dr. Gass’ abilities as a clinician, scientist and doctor. It gave him the uncanny ability to visualize retinal diseases in layers and he became a ‘master’ at that. He went on to describe numerous new diseases throughout his career with his knowledge of ocular pathology. An early example is choroidal osteoma. Fundus cameras were not common in the early ’60s and people handmade drawings of clinical findings with elaborate notes. Many eyes were enucleated those days for fear of tumor growth when elevated lesions were seen.

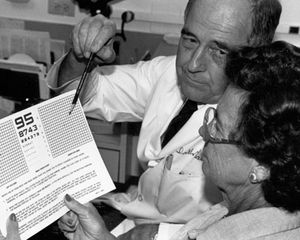

Dr. Gass instructing a patient the method of using an Amsler grid.

One such eye was sent to the AFIP during Dr. Gass’ fellowship. He learned that the lesion had thin cancellous bone in the choroid, the Haversian system of canals with blood vessels were also present and these vessels emerged on the surface resembling spiders. In the mid-1960s, as a young faculty member at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, he saw a patient with a yellow- orange elevated lesion, on the surface of which he noted spider vessels. He sent the patient to the radiology department for a plain X-ray of the skull looking for bone in the orbit. When the radiology report returned as normal, he walked over to review the X- ray himself and saw the fine, eggshell-like cancellous bone within the eye socket. Such were his clinical skills and ability to recall features in different patients and connect them up later.

Dr. Gass was recruited to the faculty of the University of Miami in 1963 by Dr. Ed Norton as a comprehensive ophthalmologist. He performed all types of intraocular surgery ranging from cataracts to glaucoma, lid and orbital procedures. Fundus and fluorescein angiography (FA) cameras were new additions to the eye department, along with Johnny Justice, a photographer who had spent a couple of years at the North Carolina Veterans Affairs hospital, (which also had housed a FA camera).

Dr. Norton suggested to Dr. Gass to see if the fluorescein camera could be used to study retinal diseases. Thus, was born his incredible journey into deep and masterful understanding of retinal diseases. He used his superior clinical examination skills; knowledge of ocular pathology and interpretation of the FA features to fully understand the clinical appearance and the pathogenesis of many retinal diseases. He went on to describe for the first time at least three dozen diseases and further understanding of many other previously recognized conditions.

Margy Ann Gass and Donald M. Gass at their home in Nashville.

When he described new retinal diseases, he named them with long descriptive names such as acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE) or acute zonal occult outer retinopathy (AZOOR) that made it easy for the novice reader to know part of the disease process just by learning the title alone. He drew many illustrations and cartoons, as he called them, with details of his understanding of pathology within the retina and choroid. His drawings from more than three decades ago are now being substantiated by modern-day OCTs.

In 1984, he wrote a paper on his understanding and interpretation of Type 2 juxta foveolar telangiectasia with blood vessels dipping from the retina and growing through the photoreceptor layers towards the sub retinal space, thinning of the inner retina with loss of inner retinal cells, partial outer retinal holes or spaces; all of which can be confirmed on present day OCT and OCTA images.

Dr. Gass’ ability to completely focus on the problem at hand and delve into it wholly, made him successful in solving many clinical issues and conditions. His uncanny ability to find the minutest changes in the patient’s fundus and the ability to remember similar features in other patients and to tie them together meaningfully has benefitted innumerable patients and physicians.

In addition to his brilliance in diagnosing and managing medical retinal diseases, he was a skillful surgeon and an innovator. He was practical and looked for simple ways to make surgical instruments more useful. He flattened the tip and made a hole in the “lens hook” that was used to hook extraocular muscles and pass the bridle sutures all in one sweep. When he was trying to decompress the vortex veins in an eye with idiopathic uveal effusion and ended up sacrificing the vein in very thick sclera, he came up with the idea to remove a significant layer of the sclera and make scleral windows that resolved the uveal effusion.

He spent three decades at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, from 1963 until 1995. His youngest son Dean was born in Miami. Dr. Gass along with Drs. Edward Norton, J. Lawton Smith, Victor Curtin and John Flynn were considered the five pillars of Bascom Palmer. Together they contributed to a significant fund of our knowledge of ocular diseases. Dr. Gass credited Dr. Norton for his unusual vision for the institute and its future. Dr. Norton’s ability to raise funds and the foresight to acquire property around the institute, along with trusting his faculty and “giving them the ball to run with” made Bascom Palmer the most successful ophthalmic institute in the country.

Dr. Gass and Mrs. Gass moved back to Nashville, his home town and his alma mater Vanderbilt in fall 1995. He continued clinical practice and described and added to our understanding of retinal diseases while at Vanderbilt. Fellows and residents were attracted to the department with his arrival. To quote Dr. Denis O’Day, the chairman of ophthalmology at that time, “The image that will forever endure for me is the one I saw every week. It is of a man sitting, surrounded by colleagues, residents, students and fellows. All are peering at photographs of the retina and the conversation is animated; all are engaged. As I walk by, I recognize our singular good fortune in having such a true academician in our midst.”

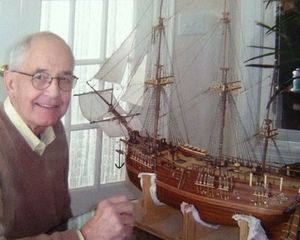

Dr. Gass credits his parents Mary and Dr. Royden Simpson Gass and his parents-in-law, Pearl Dean and J. Carlton Loser, for inspiration, support and help during their early days. Dr. Gass was not only a fabulous husband and father, ophthalmologist, and teacher; he was creative and enjoyed his pastimes immensely. He loved fly fishing and river fishing, built many wooden toys for his grandchildren and other kids in his workshop attached to the garage. His attention to details while building model ships exemplifies his core nature. A kind and easygoing personality came naturally to him. He never delayed acknowledging any present or gift with a handwritten note to the giver; I witnessed this on innumerable occasions.

He was funny and could pull a trick or two on his fellows or compatriots. He once told me this: “In the days when we didn’t know much about many retinal diseases, photos and [fluorescein angiography] were done often at every visit trying to figure out what the patient’s diagnosis could be.”

During a fluorescein conference when such a patient was presented, and the presenter went on showing several fundus photographs and fluorescein images done at multiple times, up jumped Dr. Gass with a fluorescent green Halloween mask over his face and announced, “And then the patient began to look like this.” Such was his humor. In another episode, while walking through the gift shop, he found a stick with a voodoo toy/skull attached to one end. He bought this and stuck it under his lab coat and went to grand rounds. When the patients with unknown diagnoses were presented, two older ophthalmologists at Bascom Palmer often said that they had a similar patient and that the patient went on a cruise or an exotic trip or had some obscure treatment and were cured. The next time they said something similar, Dr. Gass stood up with his voodoo stick and said that when he had a similar case, his voodoo doctor friend sent him this special stick and asked him to perform a dance that cured the patient. His eyes filled with laughter and enjoyment recalling those moments.

Dr. Gass building a Model ship.

Dr. Gass enjoyed sports, both playing and watching. He was known to hit the ball outside the park while playing softball at Bascom Palmer. The Baltimore Orioles were his favorite team. Many Monday lunches were spent discussing weekend sports events ranging from basketball to football and golf. He loved Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods for their capabilities and achievements. As a fellow, I was invited to his home in Nashville for every major sporting event – Super Bowl Sunday, college football finals and many others where we watched the game eating dinner and playing Super Bowl pool for minimal stakes, along with his daughter’s family and grandkids. He was a great cook and enjoyed barbecuing and using slow smoking cooker. I spent many weekend evenings at their home enjoying the hospitality of Margy Ann and Dr. Gass.

Dr. Gass was a special gentleman with multifaceted skills and abilities. He contributed much to science and medicine at the same time devoting time to his family and pursuing his favorite past times. Whatever he was doing he immersed himself completely and enjoyed every minute of it. To quote his son John Gass, “One could see the twinkle in his eye and a satisfied smile in his face for a job well done.” More than anything else, Dr. Gass contributed most to our knowledge and understanding of medical retinal diseases. He won every award and accolade that is known in ophthalmology and retina.

Dr. Gass was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in June 2003, and his clinical practice had to be halted prematurely. In spite of the ravages of the illness and the effects of chemotherapy, he continued writing, rendering his thoughts and opinions of cases that colleagues from across the country and the world sent him and attending teaching fluorescein conferences. His enthusiasm for a new case, a novel finding or writing a letter to the editor about an article was unchanged; all of which he did during this period. He made it to the Academy’s annual meeting in New Orleans in November 2004, where he was bestowed the Laureate award. Sadly, soon after, his health took a downturn, and he passed away on Feb. 26, 2005.

It is an honor to write about a man who was unusually brilliant and truly generous in many ways; he had great knowledge and skills and freely shared his thoughts and opinions. Most of all, he was a healer and a teacher who made each one of us a better doctor, a better teacher and a better human being.