In the course of every physician’s career, a small number of contemporaries are recognized as giants of their time.

There is a much smaller number whom medical history records as a giant for all the ages. Dr. Robert Machemer is among the latter, and it was my privilege to be one of his colleagues and friends.

Dr. Machemer was born in Münster, Germany, on March 16, 1933. His father, Helmut, was a medical doctor with a PhD and a highly respected ophthalmologist. He died in Russia during the war in 1942, leaving his wife to raise their three small boys. As the eldest son, during wartime, Dr. Machemer had to assume responsibilities that were challenging for his young age, such a riding his bike to local farms in search of food for his family. Although they lived in an area that was spared direct combat, he watched bombers fly overhead and, like most boys, played at war with his model planes. In spring 1953, after completing his “abitur,” a required exam for college entrance, he worked for six months in a steel mill to partially finance his medical education.

In fall 1953, Dr. Machemer matriculated at the University of Münster where he earned his medical degree with additional study in Freiburg and Vienna. One of the first people he met in his medical school class was his wife-to-be Christel Haller. They enjoyed studying together and eventually decided to marry. But it was common knowledge that married students couldn’t concentrate as well (a belief that was supported by three married couples in the class who were underperforming). They waited until they completed six years of medical school and after entering the two-year internship.

In fall 1953, Dr. Machemer matriculated at the University of Münster where he earned his medical degree with additional study in Freiburg and Vienna. One of the first people he met in his medical school class was his wife-to-be Christel Haller. They enjoyed studying together and eventually decided to marry. But it was common knowledge that married students couldn’t concentrate as well (a belief that was supported by three married couples in the class who were underperforming). They waited until they completed six years of medical school and after entering the two-year internship.

Dr. Machemer began his internship in Berlin and spent the second year in Freiburg studying pathology, while Dr. Haller started her internship in Düsseldorf. Professor Ernst Custodis was chair of ophthalmology in Düsseldorf, and he offered Dr. Haller a position in his residency program. She didn’t feel the specialty was quite right for her, but thought it might be right for her fiancé, so she called Dr. Machemer with the idea. Although his father had been an ophthalmologist, Dr. Machemer admitted that he hadn’t considered it for himself (he may have been thinking of internal medicine at the time). But, after giving it serious consideration, he decided to follow his fiancés suggestion, and the rest is history.

In 1962, he was admitted to the three-year ophthalmology residency at the University of Göttingen under the direction of Professor Wilhelm Hallermann. The Drs. Machemer were now a young married couple, and their daughter, Ruth, was born the following year. Living accommodations were scarce at the time, and the three lived in the attic of the Hallermann home. It was a difficult time, because Hallermann’s wife died six months before Ruth’s birth. But they carried on, with Dr. Machemer working long hours and his wife staying home with Ruth. Their attic dwelling had two sections and a small bathroom, where Dr. Machemer kept a cot that he often slept on to avoid the baby’s crying.

Dr. Machemer’s interest in research had already begun, but Hallermann only allowed him to conduct this work after 6 p.m. and on weekends. Nevertheless, it led to 16 publications in a wide range of ophthalmic topics and a desire to continue his research in an academic setting. He applied for a NATO fellowship in the U.S. Hallermann didn’t think this was a good idea and offered Dr. Machemer a position under him. Knowing the constraints that the German system placed on young scientists in those days, Dr. Machemer stayed with his original plan and got the fellowship grant. He received several offers, including positions in Boston, St. Louis and Baltimore. But Dr. Ed Norton, who was chair of the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute at the University of Miami, impressed Dr. Machemer the most by asking specific details about his research, which led in 1966 to the next, and possibly most propitious, move of his life.

He had an uncle living in the U.S., who helped the family obtain an immigration visa by vouching that they would “never be a burden to the country.” At the end of his two-year research fellowship, they decided to take a vacation up the East Coast of the U.S. as far as Canada prior to returning to Germany. Before departing on their American adventure, Norton gave Dr. Machemer a sealed envelope to “help him think” on the trip. It was an offer to become a faculty member at Bascom Palmer, with the ability to divide his time between clinical care and research as he chose — clearly the offer of a lifetime.

But Dr. Machemer’s wife initially thought it was a terrible idea. It meant that their only child would not be able to grow up enjoying a close relationship with her grandparents and other family back in Germany. Dr. Machemer agreed and told his wife that he would leave the decision up to her. Several factors influenced her momentous decision. First, of course, was the unprecedented opportunity for her husband. But another was a German woman she met in Miami who was about 16 years older than the Machemers and had become a close friend and a “substitute grandmother” for Ruth. In years to come, she would move with the family to Durham, North Carolina, where they would remain close until her death.

And so, it was that the Machemers remained in Miami, launching what would become one of the truly great episodes in the annals of ophthalmic history.

During the time since internship, Christel Machemer had been a stay-at-home mom, raising their daughter. Now she could continue her own career. After considering several specialties that would allow her to balance the demands that so many women physicians face of being a clinician, wife and mother, she settled on psychiatry. She was accepted into the residency program at the University of Miami and would go on to have her own distinguished career.

At the time that Dr. Machemer was beginning his tenure at Bascom Palmer, there was still controversy regarding the importance of vitreous in the health of the eye. It had long been felt that vitreous (sometimes referred to as “the royal jelly”) was vital to maintaining retinal function and that its loss, as during cataract surgery, was to be carefully avoided. But one of Dr. Machemer’s colleagues, Dr. David Kasner, startled everyone by purposefully removing vitreous with Weck cell sponges and scissors, at first during cataract procedures and then in an eye with vision obstructed by amyloidosis. This stimulated Dr. Machemer to think that one might be able to achieve the same result with a finer instrument, which he began to fabricate and test in his garage using an airplane drill in a syringe with a suction tube attached and a raw egg (as a surrogate for the eye and vitreous).

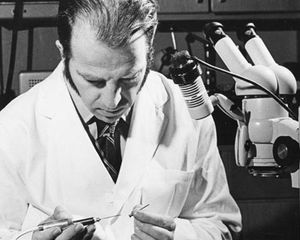

Dr. Machemer pictured in his garage, developing his prototype vitrectomy instrument.

Encouraged by the results of his nascent device, he created a more sophisticated instrument, which he called the vitreous infusion suction cutter (VISC). He first tested it with an open sky approach in rabbits into whose vitreous he injected blood. Satisfied with his results in the laboratory, he scheduled his first human patient, a person with diabetes with a longstanding vitreous hemorrhage and a cataract. After the cataract surgeon removed the lens, Dr. Machemer performed a vitrectomy with his instrument using the open sky technique, and it worked very well.

Despite his success, Dr. Machemer recognized that the open sky approach would not be optimum for delicate retinal surgery, and so he began experimenting with eye bank eyes by inserting his instrument through the pars plana to perform a vitrectomy. After convincing himself of the procedure’s feasibility, he was ready to perform his first pars plana vitrectomy in a human eye. That procedure was performed on April 20, 1970. Again, it was a patient with diabetic retinopathy and a long-standing vitreous hemorrhage. The surgery was successful, the patient’s vision improved and the modern era of vitreoretinal surgery was launched.

This initial success was followed by rapid refinement of instruments and techniques and attempts at more challenging cases. With the encouragement of Ed Norton, Dr. Machemer developed methods of treating giant tears of the retina and other complex retinal disorders. Norton felt it was now time to tell the world and he arranged for Dr. Machemer to present his work that fall at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Needless to say, the reception was dramatic. People came up to him after the talk to tell of similar work that they were doing or hoping to do, and the field of vitreoretinal surgery began to gradually expand around the globe.

Not surprisingly, Dr. Machemer was soon being asked to train other retina surgeons in the new techniques. His first course was not in the United States, but in Essen, Germany, at the invitation of Professor Meyer-Schwickerath. Before long, however, he was offering courses in Miami with the assistance of Zeiss Instruments, which provided the operating microscopes. The company was understandably happy to do this, not only because Dr. Machemer was creating a new market for their microscopes, but also because he was improving their instruments by suggesting advanced features, such as the XY movement.

Dr. Machemer’s name was now known around the ophthalmic world. But he was not resting on his laurels. In addition to his research laboratory, where he was studying proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), he established a bioengineering laboratory at Bascom Palmer in order to continue developing the wide range of instruments that were necessary for the surgical field he had created. He recruited the skilled bioengineer, Jean-Marie Parel, from Australia to run the lab, and between them they produced a steady flow of novel vitreoretinal instruments.

One of these novel instruments was an intraocular light. Dr. Machemer had tried transillumination with a light bulb from his electric train, but this was impractical for intraocular use, and Parel came up with the idea of using fiber optics, which he developed for the eye and which would become the standard for surgical endoillumination.

Meanwhile, working in his research lab on an animal model of what was then called massive vitreous retraction (MVR), Dr. Machemer discovered that it was actually modified pigment epithelial cells that were proliferating into the vitreous and that, in addition to performing a vitrectomy, it was necessary to peel a membrane from the surface of the retina. For this, he and Parel developed intraocular hooks for peeling the membranes, as well as a special diathermy for controlling bleeding and cannulas through which the various instruments could be passed into the vitreous chamber at the pars plana.

Using his knowledge from the lab and the new instruments and techniques, Dr. Machemer performed his procedure on 21 cases of MVR (later more commonly known as PVR), and all 21 failed. His 22nd case was a young boy with bilateral PVR from high myopia. Although he explained to the parents his lack of prior success, they pleaded with him to try it. He did, and with vitrectomy and membrane peeling, the procedure was a success, and the child regained useful vision and would grow up to become a lawyer. Today, thousands of patients have vision restored every year through modifications of this basic technique.

In 1978, Dr. Machemer received a call from someone inviting him to Durham, N.C. but didn’t catch the name. He said he was too busy with his experiments and didn’t have the time. The caller then explained that he was dean of the Duke Medical Center and was hoping Dr. Machemer would come to interview for the chair of the hospital’s eye center. The Machemers had previously visited Durham and fallen in love with the area, so he agreed to come and was impressed with what the school had to offer. After the standard search, in which several leading ophthalmologists were considered, Dr. Machemer was offered the position and he accepted.

One disappointment associated with their move to Duke was that Parel elected to remain in Miami. But Dr. Machemer was able to recruit another skilled bioengineer, Dyson Hickingbothum, who was already at Duke. Together they recreated the bioengineering lab that Dr. Machemer had at Bascom Palmer, which supported the continued flow of new surgical instruments for the evolving field of vitreoretinal surgery, as well as instruments for the other ophthalmic subspecialties.

Dr. Machemer expanded the retina faculty and started a retina fellowship. Some of the fellowship graduates remained on his faculty, which soon become one of the premier retina programs in the country. He also expanded the Duke Eye Center facility by adding additional and updated operating rooms. With his enlarging faculty, he needed more ophthalmic technicians, and he started an ophthalmic technician training program, which provided a pool of well qualified technicians.

Having admired his accomplishments from afar, I was intrigued to now observe firsthand Dr. Machemer’s many talents and interests and the energy with which he made the most of each one. He maintained a busy clinical and surgical practice, with referrals coming from around the country and all parts of the world. He spent hours in the lab with his fellows and residents, advancing our understanding of retinal diseases and creating new tools and techniques to treat them. He was a superb teacher, never missing a chance to teach in the clinics and during surgery. Every Saturday morning, he held lengthy rounds with all his students, and he established an annual vitreoretinal conference, that became one of the premier events of its type. And, of course, he was in constant demand as a speaker, which added world travel to his long list of activities.

He also proved to be an excellent administrator, keeping his finger on the pulse of every aspect of his department. And, like all good chairs, he cared for and nurtured his faculty. He encouraged me to write my glaucoma textbook, for which I will always be grateful, and when he learned that I was well behind my deadline on the first edition, he arranged for the two of us to spend a week of dedicated writing in North Carolina’s Smoky Mountains (citing that he also needed time to complete some writing). We would write every morning and hike in the afternoons. There were also humorous times, like the day he called me into his office to announce that “we” needed to exercise more. This led to our joining a health program in the Duke Athletic Department and working out a few nights each week after work. These are memories that I will always cherish.

Eventually, even Dr. Machemer grew weary, and after 14 years as chair, he chose to step down from that position in 1991, but remained active on the faculty for another seven years. During those final years, he continued to see patients and teach. He also created an atlas of retinal diseases so that doctors around the world could have access to this learning tool. And, not surprisingly, much of his time was occupied accepting the honors and awards that flowed in from around the world: the Ernst Jung Prize, Howe Medal, Hellen Keller Prize for Vision Research, Gonin Medal, Proctor Medal and the Gullstrand Medal of Sweden.

In 1998, as health issues were beginning to surface, Dr. Machemer retired. The following year, he was inducted into the ASCRS Hall of Fame, and in 2003 he was the recipient of the Academy’s Laureate Recognition Award. He remained active and focused in his retirement. Having always enjoyed models, he now had the time to build exquisite remotely controlled model sail boats and airplanes. One of his last interests was metal work, and he built a clock from scratch, fabricating every cog and wheel from sheet metal. This was his nature; to always think and create. But, in 2009, he learned that he had terminal cancer, which he faced with the same courage that had marked all his days. He died on Dec. 23, 2009.

The following year, a group of former trainees and colleagues created The Robert Machemer Foundation to “support education, research and training…in the vitreoretinal surgical field” by providing an annual research scholarship “to honor the father of modern vitreoretinal surgery, our mentor, our colleague and our friend.” A fitting tribute to a giant for all the ages.

A note from the author: My sincere thanks to Dr. Christel Machemer for our conversations that helped fill in the gaps, and to Dr. W. Banks Anderson, Jr., whose excellent interview with Dr. Robert Machemer for the Academy’s oral history project provided many of the details for this article.