Stuart Fine, MD, served as a professor of ophthalmology and director of the Retinal Vascular Center at the Wilmer Eye Institute until 1991 and then served for 19 years as professor and chair of ophthalmology and director of the Scheie Eye Institute at the University of Pennsylvania.

In 2011, Dr. Fine stepped down from his position at Penn and relocated to Colorado, where he is a part-time clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. He has made several seminal contributions to ophthalmology and has trained many of our current leaders.

Stuart Fine, MD

Among his many awards of recognition are the Jackson Memorial Lecture, the Lifetime Achievement Award of the AAO, the J. Donald M. Gass Medal from the Macula Society, the Distinguished Alumni Award from the University of Maryland School of Medicine, and his presidency of the Association of University Professors of Ophthalmology (AUPO).

Alfredo A. Sadun, MD, PhD: Stuart, thanks for this opportunity. This is going to be one of a series of interviews with luminaries in ophthalmology that has several purposes. I’ll be particularly interested in creating a sense of the world of ophthalmology, particularly academic ophthalmology, when you began your career. Young ophthalmologists, especially residents and fellows, are likely to be surprised to learn how different things were “back then.”

Can you start us off with comments about your early life?

Stuart Fine, MD: I was born and reared in Baltimore, MD. My family lived in a safe neighborhood. My elementary school was four blocks from home. We walked home every day for lunch and then walked back to school.

Dr. Sadun: When did you get interested in becoming a doctor?

Dr. Fine: In those days, the 1940s, pediatricians made house calls on sick patients. I was always excited when I knew that my pediatrician would be coming to see me, even though his visit often meant that I would be getting a shot of penicillin. I guess he was my first role model.

Dr. Sadun: Tell me about your education.

Dr. Fine: I attended the University of Maryland in College Park, Md., and majored in philosophy which was an unusual major for a pre-med student. Also unusual was that I was just 16 years old when I started college, a full two years younger than most of my classmates.

Dr. Sadun: How did being just 16 affect your college experience?

Dr. Fine: Because of my youth, I had missed out on a lot of social life in high school. In college, I joined a fraternity in my freshman year. Living in the fraternity house exposed me to many distractions, such as nightly ping pong games, poker games and hours of late-night schmoozing. I was making up for what I had missed in high school.

Dr. Sadun: How did all that socializing affect your grades?

Dr. Fine: Predictably, my grades suffered. By the end of my junior year, I realized that I would have to turn up the steam if I expected to be admitted to medical school. I moved out of the fraternity house and became a serious student. Fortunately, I convinced the pre-med adviser and the medical school admissions committee that I had turned the corner and was committed to becoming a physician.

Dr. Sadun: So, you stayed in Maryland for college and for medical school. Is that when you got interested in ophthalmology?

Dr. Fine: Definitely not! Students rotated on the ophthalmology service for just two days! On one day, we did histories and physicals on the inpatients who were scheduled for cataract surgery by the residents. On the second day, we were assigned to the operating room but we were stationed at the foot of the OR table so we couldn’t even see the eye! Ophthalmology was not even a remote consideration in medical school.

Dr. Fine with then Hopkins medical student Beth Bromberg, who was taking an ophthalmology elective.

Dr. Sadun: I’m looking forward to hearing about how you got to ophthalmology but first tell me about your internship.

Dr. Fine: I was a straight medicine intern at the University of Maryland Hospital. The year included two months of electives and I chose general surgery and urology, unusual choices for a medical intern.

Dr. Sadun: What were you thinking about for residency?

Dr. Fine: I thought that I wanted to be a neurosurgeon. At that time, there was a draft and doctors were eligible to be drafted up to age 35. The Berry Plan was the military’s way of assuring that each service (U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force) would have adequate numbers of specialists to meet its future needs. Every year, each of the armed service would defer a certain number of medical school seniors in each specialty in order to meet those future needs. The selection was by lottery. I applied for a deferment in neurosurgery but was not deferred. Not having a deferment meant that most residency programs would not accept you for fear that you might be drafted in the middle of the residency. In 1966, the year that I graduated from medical school, not having a deferment meant that you would be headed to Vietnam.

Dr. Sadun: So, what happened next? You didn’t have a deferment and you didn’t have a residency.

Dr. Fine: I was married and had an infant daughter, so obviously, I wanted to avoid going to Vietnam. I made many phone calls and eventually identified a program in the public health service in Arlington, Va. that had an opening for a nonresidency trained generalist. I was accepted to begin a two-year tour of duty beginning July 1967 after completing my internship.

Dr. Sadun: What was your job in the public health service?

Dr. Fine: There was actually not much for me to do although I had an impressive title, an office with a window, and a full-time secretary. I spent most of my time organizing an international symposium on the treatment of diabetic retinopathy that was held at the Airlie House in Warrenton, Va. in September 1968. More about that later.

Dr. Sadun: Having had only two days of ophthalmology in medical school, what did you know about diabetic retinopathy?

Dr. Fine: Not much! I mentioned that I was a generalist in the public health service program. Just down the hall from my office, there was another young doctor who was fulfilling his military obligation by serving two years in the program. He had just completed his chief residency at Hopkins: his name was Mort Goldberg, MD.

Dr. Goldberg became my friend and my mentor. He invited me to accompany him to weekly grand rounds at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday mornings and to grand rounds at the Naval Medical Center at Bethesda on Wednesday afternoons. On some Tuesdays, we attended ophthalmology research conferences at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and on Saturday mornings we attended lectures at the Washington Hospital Center. After a few months of exposure to ophthalmology at that level, with Dr. Goldberg as my mentor, I was ready to apply for a residency in ophthalmology.

Dr. Sadun: This was in 1967, before the ophthalmology match. What was it like applying for a residency then?

Dr. Fine: Crazy! As you might have guessed. Dr. Goldberg guided me as to where I should apply. The programs at Massachusetts Eye and Ear and at the University of Wisconsin were filled for the next three years! I applied to eight programs and interviewed at seven. I withdrew from two programs after the interviews. I was accepted at three programs and chose the University of Florida in Gainesville.

I should mention that I interviewed there in February when it was freezing cold in Virginia. In Florida, everyone was wearing short sleeve shirts. More importantly, I liked the principal faculty in Florida: Herb Kaufman, MD, and Mel Rubin, MD. During my first year there, David Worthen, MD, joined the faculty after completing his residency at the Mass Eye and Ear. Dave was the whole package: compassionate physician, kind and capable teacher, superb surgeon, insightful investigator, and a friend to the residents. His untimely passing from ALS was a huge loss not only to his family and friends, but to all of ophthalmology.

Dr. Sadun: You were being interviewed for a residency in a field where you had never even taken an elective rotation. How did the interviews go?

Dr. Fine: That was not a problem. I had learned a lot of ophthalmology during my two years in the PHS and I had learned especially about diabetic retinopathy because of my role in organizing the Airlie House symposium on the treatment of diabetic retinopathy. With regards to interviews, Dr. Goldberg was again very helpful. I once mentioned to him that I thought there were many similarities between ophthalmology and urology, a service on which I had spent one month during my internship.

Both disciplines cared for men and women, adults and children, both had interesting diagnostic procedures, and both were treatment oriented. I then compared looking at the bladder through a cystoscope with looking at the fundus with an ophthalmoscope. At that point, Dr. Goldberg cringed: “If you mention that similarity during your interview, I can guarantee that you will not get a residency.”

Dr. Sadun: Any interesting stories from your residency worth sharing?

Dr. Fine: It was a traditional residency with rotations to all the specialty services, plenty of patients, a wide variety of pathology, good teaching conferences, and capable co-residents. During my chief residency year, Dr. Kaufman asked me to go over to the University of Florida School of Veterinary Medicine to do an eye examination on a racehorse.

The horse’s owner from Jacksonville, Fla. was concerned that the horse was continually running into the fence while running around the racetrack. It was obvious from just a hand light exam that the horse had a significant cataract in the left eye. The next question was how to perform a lens extraction on a horse. Should we do an intra-capsular extraction which was standard for humans or an extra-capsular procedure? Iridectomy or no iridectomy? Steroids or no steroids? Antibiotics or not?

I read several papers in reputable veterinary journals and telephoned ophthalmologists at two vet schools: Cornell and Penn. Unsurprisingly, I got varying opinions. Along with my co-resident, Jeff Horwitz, MD, we performed an extra-capsular procedure under general anesthesia. I’m happy to report that the procedure went well and that there were no short-term complications. I do not have long-term follow up so I cannot report whether the horse ever returned to the racetrack and won a race.

But it was a fascinating experience, including watching the administration of intravenous sedation in a vein in the leg and the insertion of an endotracheal tube almost 2 inches in diameter in preparation for inhalational anesthesia.

Dr. Sadun: So, how did you decide to do medical retina?

Dr. Fine: It was my interest in the retina — in diabetic retinopathy in particular — that led me to ophthalmology. By the way, the term medical retina didn’t exist at that time. In those days, being a retina specialist meant performing scleral buckling procedures on patients with retinal detachment. I had spent six months on the retina service with Mel Rubin, MD.

During that time, I assisted on more than 200 scleral buckling operations. I didn’t love doing those procedures, and I wasn’t particularly good at finding all the small holes in patients with aphakic detachments. What fascinated me was the possibility of being able to treat previously untreatable conditions like diabetic retinopathy with laser photocoagulation and visualizing the retinal blood vessels with fluorescein angiography of the fundus.

Just as there was no residency matching program in ophthalmology, there was no fellowship matching program. I sent letters inquiring about a retina fellowship to Drs. Edward Okun at Washington University, Dr. Arnall Patz at Wilmer, and Edward Norton in Miami. In my letters, I indicated that I did NOT want to do retinal detachment surgery during the fellowship.

Instead, I wanted to learn about diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, retinal vascular occlusions, choroidal nevi and melanoma and angioid streaks. I also wanted to become proficient in interpretation of fluorescein angiography and in performing argon laser photocoagulation, both in their infancy at that time. Dr. Okun called me. He said that he had never taken a fellow who did not want to do retinal detachment surgery and that he already had accepted a retina fellow to start in 1969.

Nevertheless, he offered me a position to start in 1970. Dr. Patz called and offered me the position that I described upon completion of my residency. When I called Dr. Norton to inform him that I had decided to go to Hopkins, he apologized and said he regretted that he had never received my letter.

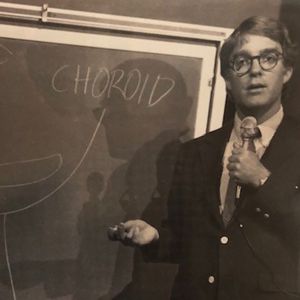

Dr. Fine lecturing in Lister Hill Auditorium at the National Institutes of Health during a press conference to announce results from Macula Photocoagulation Study (May, 1982).

Dr. Sadun: So, you were a retina fellow who did not do retinal surgery. What was your fellowship like?

Dr. Fine: It was fabulous!

Dr. Sadun: And there was Dr. Patz, a legendary figure in ophthalmology. He received the Lasker Award by documenting the relationship between high arterial oxygen and retrolental fibroplasia (now called ROP). What was it like to work with him?

Dr. Fine: Again, fabulous! He always made his fellows feel like they were one of the world’s experts. In the presence of a patient that I had worked up, before presenting the history and findings to Dr. Patz, he would say, “Now that you’ve seen Dr. Fine (or whoever the fellow might be), you’re at the very top of the totem pole and you can’t go any higher. He also could think on his feet quicker than anyone I’ve ever met.

Once he asked a patient to leave the laser room because there was an emergency need for the laser. The patient said that she saw a rabbit being taken into the laser room on a gurney and she wondered whether this was the emergency. Dr. Patz immediately explained to the patient that the rabbit was being used to calibrate the laser so that it was now perfect for her eye. The patient smiled and thanked him.

As I mentioned, fluorescein angiography was in its infancy. Dr. Don Gass was publishing regularly about the angiographic features of various maculopathies. And most centers did not yet have an argon laser with a slit lamp delivery system. Consequently, Dr. Patz’s service was extremely busy. We saw upwards of 50 patients a day, five days a week and the patients came to Wilmer from all over the country. We also were participants in the diabetic retinopathy study which began just about the time I started my fellowship.

Dr. Sadun: Sounds like a busy year? What next? Did you think about private practice?

Dr. Fine: Since medical school, I thought that I would remain in academics; I admired my teachers and mentors and enjoyed the camaraderie of colleagues and students and house staff.

Dr. Sadun: Tell me how and why you ended up at Wilmer.

Dr. Fine: My fellowship provided me with important skills in fluorescein angiography interpretation and laser photocoagulation which not many retinal surgeons possessed. As a result of having these marketable skills, I had job offers from Drs. Mort Goldberg at University of Illinois, Matthew Davis at University of Wisconsin, Jim Elliot at Vanderbilt and Dr. Patz at Hopkins. All were excellent opportunities, and I likely would have been happy at any of those spots. I decided to stay at Wilmer for two reasons: first, I loved my fellowship and loved working with Dr. Patz and second, Ellie’s and my families were in Baltimore. Ellie and I had been married since the end of my second year of med school. We had children ages 6 and 3 years, and both of us had our parents and lots of relatives in Baltimore.

Dr. Fine has been a mentor, a role model, and an inspiration to many leaders in ophthalmology, including those fortunate enough to have worked with him as medical students or residents or fellows. His voice, dapper appearance with his bow tie, stamina and willingness to delve deeply into the pathophysiology of eye diseases have become iconic. I thank him for sharing with our communities his reflections on the start of his career.