Arnold R. Rabin, MSEE, MD, completed his medical school training at Boston University and then went on to do a residency in ophthalmology at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary (MEEI) of Harvard Medical School.

This is where we met as I was a PGY2 in 1979 when he was a PGY3. I remember Arnie as a friendly and studious resident. He was interested in electrophysiology and retinal degenerations that probably presaged one of his important contributions which was a paper in Nature Genetics in 2000 on Stargardt Disease. However, this interview concentrates on his interesting avocation. So, I pick up the interview here.

Alfredo A. Sadun, MD, PhD: Hi, Arnie. Much has happened in your life since we shared patients at MEEI. But let’s back it up to when you first became interested in ham radio. How old were you?

Dr. Rabin: Hi, Alfredo. I was about 12, and I tried to build a crystal radio. I found that experimenting with a 1N34 Germanium diode, a crystal earphone, and using a cold-water pipe in our house (as a ground), I could hear a local radio station WOR in New York. Just by holding one terminal of the earphone to the pipe, the other to the diode and the diode, back to the pipe, I could hear radio broadcasts without having to rely on complicated wiring diagrams or any source of power. It was an exciting discovery for me at that time and left a lasting impression.

Dr. Arnold Rabin, WN2ABM, at his novice radio station in May 1963. The homebrew transmitter sits atop a Hammerlund Hq 129X receiver. His left hand is on a telegraph key.

Dr. Sadun: I can imagine. You tapped into an invisible energy and information source. I’m sure you wanted more.

Dr. Rabin: Well, yes. When I was 13, my father bought me a Grundig Majestic imported German radio that had the frequency listings of all the world cities that you might be able to hear. It was exciting for a child who knew little or nothing about radio, to be able to turn a dial and in so doing, hear voices from around the world.

Dr. Sadun: Was there one place you were particularly attracted to?

Dr. Rabin: Yes. Radio Moscow was particularly strong and in perfect English. It became apparent to me that its goal was to target Americans and to broadcast its view of the news in the same way that the Voice of America or Radio Free Europe broadcasted to the USSR and Eastern Europe.

Dr. Sadun: What was the most memorable broadcast?

Dr. Rabin: In 1960, I heard Radio Moscow broadcast that they had captured an American spy plane and that the pilot was in their custody. But I couldn’t get confirmation on “CBS Evening News,” so I had to consider that this was just Russian propaganda. It only came out later that an American U2 spy plane flown by Francis Gary Powers, a U.S. Air Force pilot, had been shot down while overflying the Soviet Union. The pilot managed to bail out and survive and was in the custody of the Soviets. Since that experience, I’ve always gone to great lengths to verify the accuracy of sources.

Dr. Rabin performs an electroretinogram at Albany Medical College on the system he built as a first-year medical student in 1973.

Dr. Rabin performing an electroretinogram at Albany Medical College on the system he built as a first-year medical student in 1973

Dr. Sadun: And the next step in your education in electrical engineering?

Dr. Rabin: The following summer, my family vacationed in the Catskills where the lifeguard was operating what looked like a radio station. This was Irving Binger, a man in his 60s who turned out to be a New York City High school teacher. He was operating a radio transceiver and speaking to people in Rome! He had strung up a wire antenna over one of the structures near the pool. There he was, sitting in his lifeguard attire while in conversation with people all over the world! Amazing! Fantastic!

When I returned to the ninth grade in 1960, I discovered that one of my classmates had a ham radio station. He taught me the logistics of getting a novice amateur radio license from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). To be licensed, you had to send and receive Morse code at five words per minute and pass a written examination. The license permitted one to transmit only by Morse code using up to 75 watts of power. I purchased a used Hammarlund HQ-129X receiver for $75.

Dr. Sadun: So, you were ready to go on air?

Dr. Rabin: Not quite. That was just the receiver. To complement it, I built a Homebrew Novice transmitter by myself from a magazine called Radio TV Experimenter, which had a picture of a 75-watt transmitter for Novice amateur radio operators. This contained two tubes and transmitted in Morse code only. This was not a kit; you had to build it from scratch. The chassis consisted of a U.S. Army ammunition tin, which was army surplus.

Dr. Arnold Rabin

Once I got my license, I was good to go. The most amazing thing was to listen to the receiver with headphones and to hear a station calling me “WN2ABM” in Morse code. I was on top of the world. Every waking hour that I was not in school or doing homework, I was down in our basement, in a modified storage workshop, on the air, talking to people from all over the world using Morse Code.

Amateur radio telegraphy follows a strict protocol. Call letters, name, location and signal strength. Then we talk about our equipment and our lives. In a few months my speed was over 13 words a minute and I passed my General license exam and became WB2ABM. Every contact is logged. I met ham radio operators in every state and a few countries.

In a few months, my speed went from five words per minute to over 13 words per minute sending and receiving Morse code.

Dr. Sadun: How do you talk about the frustrations of being a teenager at 13 words a minute?

Dr. Rabin: I had to obtain a transmitter that could broadcast audio in addition to Morse code. I purchased a HeathKit Apache transmitter kit. (HeathKit was a company that provided many different types of electronics in kit form that you would have to assemble.)

Dr. Sadun: Here’s a hard question that I always ask. How did this experience impact on your career as an ophthalmologist?

Dr. Rabin: Amateur radio and experience with electronics led to electrical engineering at the City College of New York (CCNY), and a job at RCA Aerospace Systems in Boston, where I was responsible for the calibration and performance of the Rendezvous Radar on the Lunar Excursion Module of the Apollo 11.

While completing my master’s degree at Northeastern, I received a phone call inviting me to interview for a position in Eliot L. Berson, MD’s, lab in the department of ophthalmology. He hired me on the spot, and I was appointed to the Harvard Medical School Faculty as a Research Associate in Electrical Engineering.

Dr. Sadun: Dr. Berson was an exacting man. How was it working for him full-time?

Dr. Rabin: I was 25, Dr. Berson was 34, and he had just started this laboratory at the Harvard School of Public Health. Eliot had observed as a fellow that when electroretinograms (ERGs) were decreased in amplitude in patients with retinitis pigmentosa, they were also delayed in implicit time. However, Stephen J. Fricker, MD, also at MEEI and an engineer, had reported that implicit times were shortened by RP. I tried to resolve this disagreement.

Upon reviewing Dr. Fricker’s paper it was apparent that he was measuring time and amplitude using polar coordinates. The angle he interpreted to be an increase of phase by 30 degrees was actually a decrease by 390 degrees.

Dr. Sadun: What happened?

Fundus photographs of five taurine-depleted cats showing various stages of retinal degeneration. The normal control is upper left. Photo: Investigative Ophthalmology

Dr. Rabin: Electroretinography was still in its infancy. I wrote the first published description of a calibrated state-of-the-art system for recording ERGs. It was published in the Archives of Ophthalmology.

Dr. Sadun: Any other big victories?

Dr. Rabin: I got to know the members of the Department of Nutrition well, particularly K.C. Hayes. I offered to measure ERGs on any of the animals that he thought might have eye problems associated with deficiencies of different nutrients. One day K.C. called me and asked me to examine a group of cats that were being fed a semi‑purified diet.

After dilation I examined them with an indirect ophthalmoscope. All of the cats fed the diet had lesions in the area centralis, which is the area in a cat’s eye which is comparable to the macula in the human eye.

I developed a method for recording rod and cone ERGs from cats. I looked at five cats, and all of them had lesions at different levels of progression, depending on how long they had been on a diet in which casein had been the sole source of protein. I recorded ERGs from these cats, and they were all decreased in amplitude (both rods and cones). There was no question that these cats had developed a retinal degeneration due to their diet.

Hayes realized that casein, the sole protein source in the cats’ diet, lacked taurine. That spring after starting medical school, I submitted four papers in one at Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) on a new nutritional model of retinal degeneration.

Subsequently taurine has been added for parenteral nutrition for humans and in September 2022, the Food and Drug Administration approved the use of taurursodiol as a new treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), so I think it’s fair to say, that the implications of this study were very significant.

Dr. Sadun: So, you went to medical school as a technical consultant for electrophysiology? Did that determine ophthalmology as your main interest?

Dr. Rabin: Not entirely. I was interested in everything, so I did a rotating internship which included neurosurgery, emergency medicine and even obstetrics-gynecology. My internship made me realize how fortunate I was to have a residency in ophthalmology.

Dr. Sadun: What were your formative experiences at MEEI?

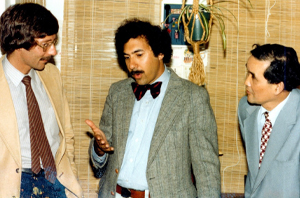

Dr. Rabin (center) at his home in Wakefield, Mass. in 1979 explaining modulation to his residency partner, Drs. Henry Kriegstein (left) and Chuo Ni (right).

Dr. Rabin: As a second-year resident at MEEI, I met Shirley Wray, MD, our neuro-ophthalmologist. She offered me a stipend to run the visual evoked potentials (VEP) laboratory that she had in the Warren building over at Massachusetts General Hospital.

At about this time, Felipe I. Tolentino, MD, at the Retina Associates asked me to record ERGs for a study on the toxicity of intravitreous Miconazole.

While on the eye pathology service I worked alongside Dr. Chuo Ni. Dr. Ni was a visiting scholar from Shanghai who had suffered a great deal due to the Cultural Revolution of Mao. Dr. Ni was sent to work on a rural farm after having been imprisoned. Ni had extensive experience in eye and general pathology. He expressed an interest in the radio station I had in Boston because it was forbidden in China. In 1984, Dr. Ni arranged for me to visit Shanghai and lecture on electroretinography.

In summary, I see myself primarily as an engineer. I chose ophthalmology because its employs more technical knowledge and engineering precision than other specialties.