Public speaking to even small crowds prompts sweat and tremors for many — never mind speaking to a crowd of thousands, comprised of so many peers and leaders in your field that almost all possible future bosses may be listening. That was the task Alfred Sommer, MD, MHS, faced, one October morning in Dallas, a few weeks into his second year of residency. It was also the day his slides caught fire.

As disastrous as it seemed at the time, his unintentionally dramatic presentation proved a portent of the future. Almost 20 years later, the research that began that fateful fall day in 1974 finally caught fire with the World Health Organization and UNICEF, resulting in policy changes that have literally saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of children. This fall, he received the Academy’s Laureate Award — its highest honor — at the 2011 Annual Meeting in Orlando.

He has found this professional success not by seeking it, but by following Yogi Berra’s advice: “If there’s a fork in the road, take it.”

“You can’t do randomized trials on forks in the road,” Dr. Sommer said during an interview in Orlando. “What I’ve done, for the most part, and what I advise other people to do is, do whatever at that moment turns you on. Whatever you find most exciting — the thing that will be more likely to get you up early in the morning, revved up or keep you up late at night, thinking about it. Might the other fork have been a better choice? Who knows? You’ll never know that. Don’t worry about it. There’s going to be another fork in the road.”

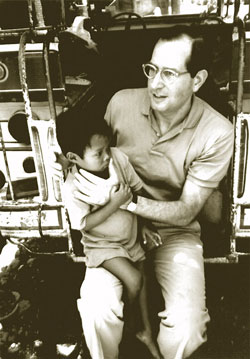

Dr. Sommer during an exam for xerophthalmia in the Philippines in 1988. The trip was taped for a 20/20 segment with Hugh Downs.

In the early days of his medical studies, Dr. Sommer was fairly sure his fork would not be ophthalmology. He planned on internal medicine. He used to tease all his friends who chose the specialty that they wouldn’t be “real” doctors because they wouldn’t be using a stethoscope. But, in the second year of medical residency (about 1968), he changed his mind. “They’ve never let me forget that,” he grinned.

The next major fork came not long after, when Dr. Sommer got a letter that he’d been drafted to Vietnam out of the Peace Corps (for which he and his wife had signed up while he was still in medical school). There were a couple draft-fulfilling alternatives, but since he was “hopeless in the laboratory” and interested in infectious disease, Dr. Sommer chose the CDC option.

To South Asia Via Atlanta

He and his wife made the move to Atlanta in the summer of 1969, but Dr. Sommer soon became restless. “The office that I was assigned to was not very interesting,” he recalled. After six years of the fast pace of medical school and residency, he was “keen to do things.” So when a couple of CDC employees from the Cholera Research Laboratory came through to recruit for a project in what is now Bangladesh, Dr. Sommer wasted no time volunteering.

“They were so excited about what they were doing,” he said. “And here was an opportunity to go overseas. It was in the developing world, which was what we had wanted to do in the Peace Corps.”

By April 1970, the Sommers and their six-month-old son were on their way to East Pakistan, as it was known then. Dr. Sommer was almost immediately immersed in addressing immense needs. First, a smallpox epidemic hit. Then, in November 1970, the Bhola cyclone hit. In one night alone, 250,000 people were gone, Dr. Sommer said.

The tragedy gave him a chance to do the first-ever epidemiological study of a disaster, on the strength of one three-week epidemiology course he’d had at the CDC. Despite his inexperience, Dr. Sommer’s work helped launch a whole new field of study: disaster epidemiology. “I made it up as I went along,” he said.

When a civil war gripped the country, the Sommers were evacuated and soon returned to Baltimore, Md., where Dr. Sommer was due to begin his ophthalmology residency. Because of his newfound passion for epidemiology, though, he made an audacious request to delay his residency a second time. It was honored. After completing a one-year master’s degree in epidemiology, Dr. Sommer finally began his ophthalmology residency in 1973.

A Serendipitous Collaboration

Dr. Sommer’s time at Wilmer Eye Institute in Baltimore coincided with the lengthy tenure of Edward Maumenee, MD, as department chairman — a man Dr. Sommer calls a “giant of ophthalmology.” One day, Dr. Maumenee sent a childhood friend, Dr. Susan Pettiss, to Dr. Sommer for help with a new job she’d started at what was then the American Foundation for the Overseas Blind (now Helen Keller International).

Since the late 1960s, the organization had been increasingly focused on not just helping the blind but also preventing blindness. They had to decide to focus first on vitamin A–related blindness. At that time, it was known that vitamin A deficiency (xerophthalmia) and blindness were connected. Not known were three significant things: the prevalence of xerophthalmia, the clinical staging and the most effective treatment. It was also unknown why children did or didn’t get it and how it might be prevented, if possible. To help Dr. Pettiss answer these questions, Dr. Sommer began setting up long-distance, organized trials in El Salvador and Haiti, with periodic visits to check on things.

“It was astonishing that almost nobody locally recognized that this was a serious problem,” he said. A typical trip included hospital rounds with the professor of pediatrics, but when Dr. Sommer would ask about cases of xerophthalmia and corneal blindness, he’d usually be told these were uncommon. Then he’d ask to see the diarrhea wards.

“There’d be all these little shrunken, skinny, severely malnourished kids lying there with their eyes closed,” Dr. Sommer said. “I used to make a paperclip retractor — if you just take a paperclip and bend it, you have a very cheap, disposable retractor — so I’d always walk around with a box of paperclips.”

As soon as he started lifting eyelids with his paperclip retractors, he found blindness. Down the chain of command would go surprise and demands for answers until they reached the nurse. “She’d say, ‘I wrote in the chart, “There’s something wrong with the kid’s eyes,” and nobody paid any attention to it’,” Dr. Sommer recalled.

Back Overseas

By the second year of his ophthalmology residency, Dr. Sommer had completed two studies. In 1974, he was invited to a World Health Organization-sponsored meeting in Jakarta, Indonesia, to discuss his work. The location proved significant. Indonesia was known for prevalent vitamin A deficiency, as well as long-standing research on the problem, particularly by two Dutch physicians.

Dr. Sommer examines a child for xerophthalmia in Bandung, Indonesia, 1976.

After the meeting, he obtained funding to do further research at the 250-bed eye hospital in Bandung, a mountainous urban center.

The move was not without discouragement from others. Dr. Sommer had been offered a faculty job at Wilmer, and as one friend saw it, was “the leader of a field that’s only beginning.” But Indonesia was the more exciting option, so off he went.

Four years later, Dr. Sommer finally returned to Johns Hopkins, determined “to do stuff that was domestically important as well.”

He began seeking NIH grants for various projects, such as a study evaluating nerve-fiber layer defects (a continuation of early-detection work on glaucoma he’d done as a resident). Another NIH grant funded what became the Baltimore Eye Survey, a study that set the standard for eye-related epidemiological research and was the first to show that African-Americans had a much higher risk for open-angle glaucoma.

The Surprise in Old Data

Dr. Sommer reviews data with a colleague in Nepal, 1994.

Just as he was beginning his NIH studies, Dr. Sommer found out he’d been nominated for membership in the American Ophthalmological Society (AOS), which required submission of a thesis within three years.

At the time, the only real data he had to write about was vitamin A, so he began poring through the findings. Perhaps he hadn’t noticed before because of the study’s focus on the relationship between vitamin A deficiency and blindness, but this time an additional trend caught his eye. The patients with severe deficiency “seemed to be disappearing disproportionately.”

In fact, they were dying much more frequently than those without the eye condition — between three and nine times more frequently, depending on the severity of vision changes.

With his new finding, Dr. Sommer’s thesis took on larger significance. He went on to write up his discovery in two simultaneous 1983 publications: as the lead article in Lancet and his thesis for AOS.

Long Road to Change

The research was ignored. “There was not one letter to the editor,” Dr. Sommer said.

Undaunted, he decided to see what would happen when children were given vitamin A supplements. Based on only biannual treatments of vitamin A (with doses much higher than the vitamins people take as daily supplements), he reduced the mortality rate by 35 percent.

These findings, too, were published as a lead article in Lancet. And people finally noticed, but not in a good way. “That brought out the long knives,” Dr. Sommer said. “That got people really angry.”

He had just proven that a simple, “two-cent” oral supplement could save lives on a substantial scale – something one would expect to be celebrated rather than savaged. Why the resistance?

“That was not the belief system,” Dr. Sommer said. Paraphrasing the German physicist Max Planck, he said, “You never change the minds of those who have a preconceived notion; they eventually die. That’s how scientific paradigms change.”

Dr. Sommer examines a child for trachoma and xerophthalmia, part of a 1989 survey in Zambia.

So he kept doing trials.

When his team would get discouraged about a new round of criticism, he’d tell them, “Don’t get angry. We’re not going to have this war of words. We’re just going to bury people in data.”

By 1992, eight major trials had been completed. As Dr. Sommer notes in a brief 2008 history of vitamin A deficiency, nearly all the trials showed a “clinically and statistically significant” change in mortality. Of the six trials in Indonesia, India and Nepal, five showed reductions in mortality ranging from 29 percent to 54 percent.

Dr. Sommer decided that was it. “I’m not doing any more trials,” he said. “One, it’s boring and two, it’s unethical.”

He called a meeting at the Rockefeller retreat in Bellagio, Italy, assembling some of those who’d worked on the studies, those who’d worked on similar studies, and some scientists and physicians in related fields. His goal was “broad agreement … widely disseminated,” with an end result of policy change.

To simplify matters, he asked the group to consider three questions in light of the data: Was vitamin A deficiency bad for kids? Would dispensing vitamin A reduce overall childhood mortality? Would vitamin A reduce measles-related fatalities?

The meeting began on a Monday. Whether due to the strength of the data or the beauty of the setting (“It’s hard to have an argument there,” Dr. Sommer says), the group had reached agreement by Thursday night. Dr. Sommer typed up a brief summary they could all sign onto, then everyone agreed to publish their own reports of the meeting — what became known as the “Bellagio Brief” — in their respective journals.

Within a year, it became official UNICEF policy. Nearly 20 years later, 70 countries have vitamin A programs and half a billion capsules are given out annually.

Keys to Success

A lot of factors play into a storied career like Dr. Sommer’s: tenacity, persistence, openness to risk and of course his “forks” — those chances and choices encountered along the way. But Dr. Sommer also stresses the “freedom and encouragement” he got from early mentors. Take a favorite story about his old boss, Dr. Maumenee, working for whom involved monthly chauffeur duties to Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C.

On one such trip, Dr. Sommer had scarcely gotten behind the wheel when Dr. Maumenee put him on the spot. “Ed says to me, ‘Al, wasn’t that a great article in the AJO [American Journal of Ophthalmology] about diabetes this month?’”

“The likelihood that I would have read the AJO that month was minuscule, but as it turned out, I had actually read it,” Dr. Sommer said — the diabetes article included. “And I said, in my usual, subtle way, ‘Naw, that’s the dumbest article I’ve ever seen.’”

Dr. Maumenee took this brash reply in stride. “Why’s that?”

Dr. Sommer went on to explain the various shortcomings, then concluded, “All of clinical ophthalmology research is dumb. It’s always ‘my last five cases’ or ‘my first 100 cases.’ Nobody understands anything about epidemiology and statistics.”

“Anybody else would have asked me to get out of the car,” he says now, but Dr. Maumenee encouraged him to publish an editorial on the topic.

Although Dr. Sommer had privately decided to leave his typewriter keys undusted, he soon got a letter from the AJO’s editor. As he recounts it, the letter read, “‘Dear Dr. Sommer. Dr. Maumenee has told me about this brilliant editorial you have written,’” he said, emphasizing the tense. “Not just, ‘you’ve got a good idea, please write about it’ — this brilliant editorial you have written. ‘We look forward to receiving the manuscript by the end of the week.’”

“It’s that kind of encouragement, pushing you,” Dr. Sommer said, that helped advance his career — whether it was presenting research in Dallas or writing editorials as a resident.

When he gives advice to young ophthalmologists today, there are two key themes: When you reach a fork, take it. “You’re much more likely to be successful and productive [in something] because it turns you on,” Dr. Sommer says. “Do what really, intellectually stimulates you.”

But, at the same time, to encounter those interesting forks, you have to show up. “Forks in the road are not going to come knocking on your door. You’ve got to be out there doing stuff,” Dr. Sommer says.

And, if you’re fortunate, your mentors will give you the kind of encouragement and freedom Dr. Sommer had to set a few slides on fire en route to making a real change, not just in his profession, but in global health and policy.

* * *

About the author: Christi A. Foist is the managing editor for YO Info and the Web and Member Communications Editor for the Academy’s website.