Uveitis can be an intimidating condition to assess and triage. For certain diagnoses, timely referral can be crucial.

An organized and comprehensive approach to the uveitis patient is important to provide appropriate care for these patients. Here are five pearls to remember when seeing patients who may have uveitis and how to avoid missing important diagnoses.

-

Take a comprehensive history.

It is particularly important to obtain a thorough history in uveitis patients. By taking a comprehensive history, including medical conditions — particularly those involving immunodeficiency, medications and family history — the differential can be narrowed significantly.

For example, a patient with retinitis can either have an autoimmune cause such as Behcet’s or Susac syndrome or may have an infectious etiology. A patient with a history of compromised immunity would be at much higher risk of infection and should get immediately referred to a specialist for ocular fluid testing and intravitreal therapy.

Certain medications, such as bisphosphonates, cancer immunotherapy, live herpes zoster vaccine and intravitreal injectables, can also cause secondary uveitis. Obtaining an accurate history can reveal inciting agents that can be held or stopped, avoiding inappropriate immune suppression.

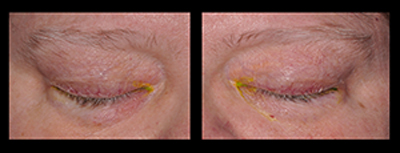

Figure 1: Poliosis and vitiligo in a patient diagnosed with secondary uveitis from checkpoint inhibitor therapy.

The patient in Figure 1, who presented with poliosis, vitiligo and panuveitis, might have been incorrectly diagnosed with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome were it not for the fact that her history of metastatic melanoma and treatment with checkpoint inhibitor was elicited (Figure 1).

-

Be discerning with ordering tests.

A slipshod approach to the uveitis workup is not always best and can be detrimental. Ordering tests without determining the clinical pretest probability of their accuracy can lead to inappropriate management.

The best way to focus the workup is to make sure that the patient is being tested for conditions that manifest with the presenting signs on exam. For example, birdshot chorioretinopathy generally presents with deep yellow chorioretinal lesions, vitritis, and cystoid macular edema, rather than anterior chamber inflammation; checking HLA-A29 without the above telltale findings can result in a false positive, as 7-10% of the Caucasian population are positive for HLA-A29.

Another common lab tes is antinuclear antibody (ANA), which can be positive in 31.7% of the general population. For uveitis, its pretest probability is greatest in the setting of occlusive vasculitis, which is the most common presentation of lupus-associated uveitis. Lupus rarely presents with standalone anterior segment inflammation; the exception to this is in pediatric anterior uveitis secondary to juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).

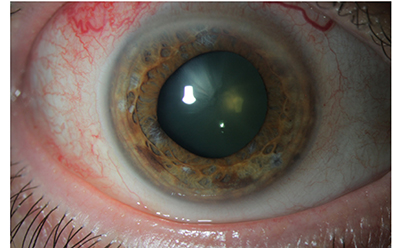

Figure 2: Slit lamp photo of iris transillumination defects in a patient who was evaluated for uveitis and tested positive for ANA. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with zoster iridocyclitis.

Image courtesy of Careen Lowder, MD, PhD - Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute Uveitis Service

Figure 2 features an image of an eye with transillumination defects – this patient tested positive for ANA, and was treated for presumed ANA-associated anterior uveitis with high-dose topical steroids only over several months before being referred and diagnosed with zoster iridocyclitis (Figure 2). The patient’s iritis was appropriately treated and controlled long-term with oral antivirals in addition to a low-dose topical steroid.

-

Always dilate the patient’s eyes.

A uveitis patient in the middle of a busy clinic can feel like a derailment, and it is tempting to cut corners in evaluating such patients. Skipping steps such as dilation can result in missing major vision-threatening diagnoses.

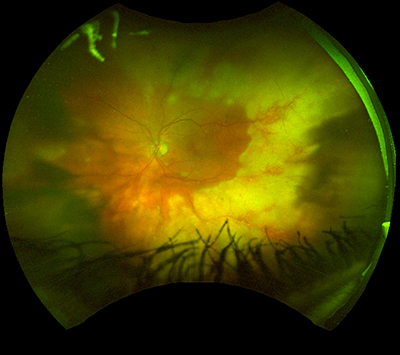

Figure 3: Fundus photo of an eye that was not initially dilated on presentation. The immunocompromised patient was later found to have acute retinal necrosis. The patient has a history of lymphoma treated with rituximab, as well as a history of disseminated zoster.

Image courtesy of Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute Uveitis Service.

In the case of an immunocompromised patient who presented with anterior uveitis and was not dilated at the initial visit, a dilated exam three days later revealed advanced acute retinal necrosis (ARN) (Figure 3).

-

Don’t forget about infection!

Failure to identify infectious uveitis can result in mismanagement. All uveitis patients should be tested for syphilis and tuberculosis (TB), not only because they can lead to manifold manifestations of ocular inflammation, but also because immune suppression in patients with a history of syphilis or TB can be life-threatening.

It is tempting to turn to intravitreal and periocular steroids to quiet inflammation rapidly, but such interventions without careful physical examination and history-taking can result in the exacerbation of severe infectious uveitides such as toxoplasmosis, syphilitic retinitis and retinitis secondary to Herpesviridae.

-

Remember — not everything is uveitis.

Finally, it is important to remember that not everything that presents with inflammation is primary uveitis. Trauma, intraocular foreign bodies, and neoplasia are examples of conditions that can result in masquerade syndromes of uveitis.

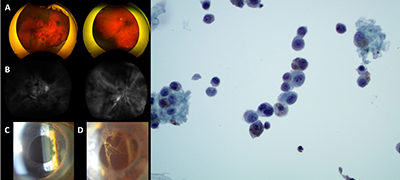

Figure 4: Fundus photos (A), Indocyanine Green Angiography (B), and slit lamp photos (C and D) of an eye initially diagnosed with uveitis secondary to checkpoint inhibitor use in a patient with metastatic cutaneous melanoma. The inflammatory cells were initially white in color but became pigmented over time. Due to suspicion of vitreous metastasis of the melanoma, vitreous biopsy was performed (right) which confirmed the diagnosis.

Remember these key points:

- Obtain a thorough history and perform a complete exam.

- Keep infectious uveitis in the differential.

- Keep masquerade syndromes in mind.

The Academy’s YO Info Editorial Board is collaborating with YO leaders from our subspecialty and specialized interest society partners and thanks the American Uveitis Society (AUS) and its Young Uveitis Specialist representative Dr. Venkat, MD, for contributing this article. The AUS Spring Meeting will be held in conjunction with the ARVO Annual Meeting on Saturday, April 30, at 4 p.m. Denver time (Mountain Savings Time) virtually via videoconference.

|

About the author: Arthi G. Venkat, MD, MS, is an assistant professor at Georgetown University School of Medicine and a retina and uveitis specialist at the Retina Group of Washington. She is the Young Uveitis Specialist (YUS) representative for the American Uveitis Society. |