Establishing the diagnosis

Case presentation

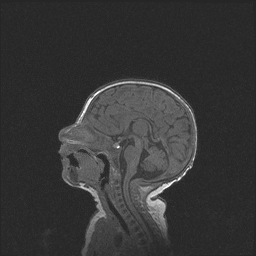

At age 5 weeks, a female child of two nonconsanguineous physicians of Jordanian descent presented with head titubation and nystagmus that had persisted and worsened since she was 1 week old (Video 1). Upon presentation, urinary and serologic testing was performed, in addition to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figures 1 and 2). The results of testing showed normal urinary levels of vanillylmandelic and homovanillic acids and a normocytic normochromic erythrocytosis with moderate neutropenia consistent with thalassemia trait, given her heritage. The MRI of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis was unremarkable. A complete history and physical examination revealed maternal Hashimoto thyroiditis, without presence of psychiatric disease or substance abuse during pregnancy, and no evidence of tumor, retinal dystrophy, or neurologic disease in the child. When the child presented again at 9 months of age, the head titubation and nystagmus had decreased in frequency, and ophthalmologic examination demonstrated central/steady/maintained vision in each eye.

Video 1. 5 week old female child with head titubation and nystagmus.

Figure 1. Axial T1 MPR sequence of MRI of the brain demonstrates normal chiasm.

Figure 2. Sagittal T1 FL 3D MPRAGE sequence of MRI of the brain demonstrates normal fourth ventricle, cerebellum, and brainstem.

Etiology

Spasmus nutans is a rare, idiopathic disorder that includes the clinical triad of nystagmus, head nodding, and torticollis, although diagnosis does not require all three findings.1 Latin for “nodding spasm,” spasmus nutans presents in the first year of life, may persist until puberty, and has been associated with lower socioeconomic status.3,4,5 First described by Raudnitz in 1897,2 the pathogenesis and neuroanatomical substrate of this typically self-limiting form of disconjugate nystagmus is still unknown. Electroretinography, electrooculography, and neuroimaging can help distinguish the clinical picture of spasmus nutans from that of other forms of nystagmus that have significant morbidity and potential mortality.

Epidemiology

The precise incidence and prevalence of spasmus nutans are unknown, but it is considered rare. Correlation of demographic and socioeconomic factors has been reviewed since the early 1900s. Several studies confirm spasmus nutans to be associated with a high incidence of rickets disease, more frequent onset of nystagmus in the darker months of the year, poor social and hygienic conditions in families, and a higher incidence in crowded sections of large cities and in children of African American descent.3,4 A more recent study at a tertiary referral center administered questionnaires to the families of 23 patients diagnosed with spasmus nutans based on clinical findings and on the analysis of eye movement recordings. The epidemiologic analysis validated that non-white ethnicity, low home luminance, and low socioeconomic status (ie, low annual income and availability of private insurance) are all associated with an increased risk for the development of spasmus nutans (Table 1).5

| Table 1. Relative risk factors for spasmus nutans estimated by Mantel- Haentszel statistics |

|---|

| Parameters | Odds Ratios | 95% Confidence Interval | Risk Ratios | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|

| Ethnicity

|

0.09

0.03 |

0.03- 0.287

0.05-0.153 |

3.32 |

1.88-5.87 |

Home luminance

- Dark room

- Brightly lit room

|

8.8

4.16 |

1.23-62.8

1.1-15.0 |

2.1 |

1.1-4.2 |

| Insurance

|

0.16

0.063 |

0.046-0.529

0.01-0.39 |

2.49 |

1.37-4.54 |

Adapted and permission requested from Irene Gottlob.5

The onset of spasmus nutans has been reported to range from age 2 weeks to 3 years, and is generally quoted as 6-12 months of age.6 Though initially thought to resolve between 3 and 6 years of age,7 more recent evidence from long-term follow up suggests there may be a persistence of subclinical nystagmus up to age 12 years.8

Pathophysiology

The cause of the nystagmus in spasmus nutans remains unknown. The disconjugate nature of the nystagmus suggests a yoking abnormality whose anatomic location may lie at the level of the ocular motor nuclei and may be caused by a delayed developmental change in the associated connections within this system.9 These delayed modifications may account for both the transient nature and the variability of the dissociated nystagmus. Other systems implicated in the development of spasmus nutans include the vergence, saccadic,10 and pursuit systems, though none in isolation can explain the observed high-frequency, dissociated, rapid ocular oscillations and normal saccades typical of the disorder.

In contrast, the head nodding in spasmus nutans is not thought to be pathological but rather a voluntarily nod as a neurovisual adaptation to compensate for nystagmus and to improve vision. In a study of 35 patients with spasmus nutans, Gottlob et al found an influence of head nodding on eye movements of 21 patients (60%).11 The fine, fast, dissociated nystagmus changes to a larger, slower, symmetric eye movement during head nodding, with both eyes oscillating in phase at the same amplitude and oscillating 180 degrees out of phase to the head movements. The head nodding disappears during sleep,9 is lower frequency than the nystagmus,11 and becomes more prominent when the child inspects an item of interest.11

Clinical Features

Reports of nystagmus in spasmus nutans vary widely, but it often appears as an extraordinarily fine, high frequency, pendular nystagmus that has been likened to an ocular “quiver”.12 It is usually horizontal in direction but may also be vertical or torsional,13 and it is often described as an intermittent nystagmus that is asymmetric or even monocular.9,11 On electrooculography, the two eyes may be out of phase with each other, which is noted clinically as dissociation.9

Head nodding may be the abnormality that first attracts attention but, as previously mentioned, it is generally agreed to be compensatory and not pathologic. Electrooculographic recordings have suggested that head nods are characterized by oblique, sinusoidal, intermittent, slow frequency, and large amplitude movements.11 In order to suppress nystagmus, the amplitude of the head nod must be higher than a certain threshold (which may differ amongst individuals).

The head tilt, or torticollis, is present in less than half of cases of spasmus nutans.14 Not many theories have been suggested about why it is present, though some authors feel it may help direct the head nodding to its optimal trajectory.11

As visual development is affected by specific alterations in early visual experience (including nystagmus), it is logical to suspect long-term visual comorbidities in patients with spasmus nutans. A retrospective study compared 18 patients with spasmus nutans against published, age-matched controls to evaluate associated visual problems including strabismus, amblyopia, anisometropia, and astigmatism. There was a significantly higher incidence of strabismus (56%, P < 0.001), most commonly esotropia, and amblyopia (44%, P < 0.01) when compared to controls.15 Another prospective case series followed 10 patients with spasmus nutans from a mean age of 20 months until a mean age of 7 years, and concluded approximately two thirds of patients had signs of congenital esotropia, dissociated vertical deviation, amblyopia, and/or latent nystagmus.8

Evaluation and differential diagnosis

Congenital nystagmus, retinal disease, brain tumors, and other neurologic diseases all share clinical findings with spasmus nutans. Since a few patients are later found to have congenital retinal dystrophies or neurodegenerative diseases, some experts advocate postponing the diagnosis of spasmus nutans until after resolution of the nystagmus—though it is rare in medicine for a diagnosis to require the future resolution of clinical findings.16

Head nodding can be found in up to 12.6% of visually impaired individuals with nystagmus, which can confuse physicians suspicious of spasmus nutans.17 Given the overlap of head nodding between sensory- and motor-type nystagmus and spasmus nutans, these entities cannot be distinguished by eye movement recordings alone. Congenital nystagmus is another condition that shares features with spasmus nutans. Gottlob et al have published criteria by which one can distinguish the two (Table 2).18

Retinal diseases such as achromotopsia,19 Bardet-Biedl syndrome,20 congenital stationary night blindness,21 and other photoreceptor dystrophies22 have all been reported in association with spasmus nutans-like nystagmus. Findings of photophobia, decreased vision, night blindness, and myopia all suggest an underlying congenital retinal dystrophy.16 Further investigation, including electroretinography, should be carefully considered, especially when visual function remains below normal.23

| Table 2. Features distinguishing spasmus nutans from congenital nystagmus. |

|---|

|

|

Positive Criteria in Spasmus Nutans (%)

|

Positive Criteria in Spasmus-Nutans-like Disease (%)

|

Positive Criteria in Infantile Nystagmus (%)

|

|

Nystagmus onset later than 6 mos

|

52

|

62

|

0

|

|

Strabismus or amblyopia

|

56

|

50

|

32

|

|

Head nodding

|

95

|

100

|

64

|

|

Horizontal OKN

|

94

|

70

|

14

|

|

Nystagmus amplitude, 1 eye < 3%

|

65

|

66

|

0

|

|

Nystagmus amplitude, OD/OS > 25%

|

90

|

55

|

0

|

|

Intermittent nystagmus

|

78

|

60

|

0

|

|

Only pendular nystagmus

|

100

|

100

|

8

|

|

Frequency of pendular nystagmus ≥ 7 Hz in 1 eye

|

78

|

90

|

20

|

|

OD/OS out of phase

|

96

|

100

|

4

|

OKN = optokinetic nystagmus; OD = right eye; OS = left eye.

Adapted and permission requested from Irene Gottlob.

Particularly notable are the diseases with spasmus–nutans-like nystagmus that have significant morbidity and potential mortality. Suprasellar chiasmal gliomas have been known to cause Russell diencephalic syndrome, which was likely the cause of what was thought to be rickets or malnutrition associated with spasmus nutans in the era before neuroimaging.16 This constellation of signs that are indistinguishable from spasmus nutans highlight the need for neuroimaging. In 1986, a series of 14 patients with spasmus nutans underwent neuroimaging without evidence of anterior pathway gliomas; 1 patient (7%) had an empty sella and an arachnoid cyst.24 Over 1 decade later, the largest series of 67 patients with spasmus–nutans-like nystagmus found no evidence of anterior pathway gliomas on neuroimaging.25 Less than half of these patients had the full triad of spasmus nutans and only 43% underwent neuroimaging; the authors also reported optic nerve hypoplasia in 2 children (7%) and white matter changes on cerebral MRI in another 2 children (7%). The most recent retrospective review by Kiblinger et al studied 22 patients with spasmus–nutans-like nystagmus and found chiasmal gliomas in 2 patients (9%).23 Only 14% of the patients had the full triad, but 91% underwent neuroimaging; the authors also reported Chiari I malformations in 2 children (9%), and 1 child each with evidence of “small optic nerves,” enlarged cisterna magna, and a small, incidental subdural hematoma. There are other reports of brain tumors associated with spasmus–nutans-like nystagmus, including thalamic neoplasm26 and arachnoid cyst.27

Another sizable percentage of patients presenting with spasmus–nutans-like nystagmus have important underlying neurologic or systemic disease. Evaluation for opsolclonus-myoclonus28 in association with neuroblastoma should include urinary catecholamines and complete body magnetic resonance imaging. Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease and subacute necrotizing encephalomyelopathy (Leigh disease) should be suspected in children with spasmus–nutans-like nystagmus and clinical signs of ataxia and/or developmental delay;16 neuroimaging is likely to demonstrate evidence of white matter signal abnormalities. Another report describes a child with a history of spasmus nutans, congenital ocular motor apraxia, and developmental delay whose MRI of the brain demonstrated hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis.29

Prognosis

As with most self-limiting ocular conditions, the prognosis for visual function in spasmus nutans is quite good. One long-term follow up study observed 10 patients over a mean of 5.5 years and concluded that all 10 subjects had vision better than 20/50.8 Additionally, 90% of patients had 20/30 vision or better in at least 1 eye, and orthotropia with normal stereovision will likely develop in approximately one-third of these patients.

References

- Katzman B, Lu LW, Tiwari RP. Spasmus nutans in identical twins. Ann of Ophthalmol. 1981;13(10):1193-1195.

- Raudnitz R. Zer Lehre vom spasmus nutans. Jahrb Kinderh. 1897;45:145.

- Still GF. Head-nodding with nystagmus in infancy. The Lancet. 1906: 168:207–20

- Herrman, C. Head shaking with nystagmus in infants. A study of sixty-four cases. Tr Am Pediat Soc. 1918;30:180–194.

- Wizow SS, Reinecke RD, Bocarnea M, Gottlob I. A comparative demographic and socioeconomic study of spasmus nutans and infantile nystagmus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002; 133:256-262.

- Osterberg G. On spasmus nutans. Acta Ophthalmol. 1937; 15:457–467.

- Jayalakshmi P, Scott TF, Tucker SH, Schaffer DB. Infantile nystagmus: a prospective study of spasmus nutans, and congenital nystagmus and unclassified nystagmus of infancy. J Pediatr. 1970; 77:177–187.

- Gottlob I, Wizov SS, Reinecke RD. Spasmus nutans: A long-term follow-up. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995; 36:2768-2771.

- Weissman BM, Dell’Osso LF, Abel LA, Leigh RJ. Spasmus nutans: A quantitative prospective study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987; 105:525-528.

- Gresty M, Leech J, Sanders M, Eggars H. A study of head and eye movement in spasmus nutans. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976; 60:652-654.

- Gottlob I, Zubcov AA, Wizov SS, Reinecke RD. Head nodding is compensatory in spasmus nutans. Ophthalmology 1992; 99:1024-1031.

- Norton EW, Cogan DG. Spasmus nutans: A clinical study of twenty cases followed two or more years since onset. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1954; 52:442–446.

- Hoefnagel D, Biery B. Spasmus nutans. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1968; 10:32–35.

- Brodsky MC. Pediatric Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2nd New York: Springer; 2010; 411.

- Young TL, Weis JR, Summers CG, Egbert JE. The association of strabismus, amblyopia, and refractive errors in spasmus nutans. Ophthalmology. 1997; 104:112-117.

- Brodsky MC. Pediatric Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2nd New York: Springer; 2010;412.

- Jan JE, Groenveld M, Connolly MB. Head shaking by visually impaired children: A voluntary neurovisual adaptation which can be confused with spasmus nutans. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1990; 32(12):1061-1066.

- Gottlob I, Zubcov A, Catalano RA, Reinecke RD, Koller HP, Calhoun JH, Manley DR. Signs distinguishing spasmus nutans (with and without central nervous system lesions) from infantile nystagmus. Ophthalmology. 1990; 97:1166-1175.

- Gottlob I, Reinecke RD. Eye and head movements in patients with achromatopsia. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994; 232:392–401.

- Gottlob I, Helbling A. Nystagmus mimicking spasmus nutans as the presenting sign of Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999; 128:770–772.

- Lambert SR, Newman NJ. Retinal disease masquerading as spasmus nutans. Neurology. 1993; 43:1607–1609.

- Smith DE, Fitzgerald K, Stass-Isern M, Cibis GW. Electroretinography is necessary for spasmus nutans diagnosis. Pediatr Neurol 2000; 23:33–36.

- Kiblinger GD, Wallace BS, Hines M, Siatkowski RM. Spasmus nutans-like nystagmus is often associated with underlying ocular, intracranial, or systemic abnormalities. J Neuro-Ophthalmol 2007; 27:118–122.

- King RA, Nelson LB, Wagner RS. Spasmus nutans: a benign clinical entity? Arch Ophthalmol..1986; 104:1501–1504.

- Arnoldi KA, Tychsen L. Prevalence of intracranial lesions in children initially diagnosed with disconjugate nystagmus (spasmus nutans). J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1995; 32:296–301.

- Baram TZ, Tang R. Atypical spasmus nutans as an initial sign of thalamic neoplasm. Pediatr Neurol. 1986; 2:375–376.

- Spaide RF, Klara PM, Restuccia RD. Spasmus nutans as a presenting sign of an arachnoid cyst. Pediatr Neurosci. 1985–1986; 12:311–314.

- Allarakhia IN, Trobe JD. Opsoclonus-myoclonus presenting with features of spasmus nutans. J Child Neurol. 1995; 10:67–68.

- Kim JS, Park SH, Lee KW. Spasmus nutans and congenital ocular motor apraxia with cerebellar vermian hypoplasia. Arch Neurol. 2003; 60:1621–1624.