Aim

The aim of trabeculectomy surgery is to create a pathway for external drainage of aqueous from the anterior chamber.1

Indications

Trabeculectomy can be indicated following failed angle surgery, especially for primary congenital glaucoma (PCG). It can be considered as a primary procedure if a surgeon is unfamiliar with angle surgery, if angle surgery is not possible, or if a patient is unlikely to respond sufficiently to angle surgery as with very early or late presentations. Trabeculectomy can be indicated when very low target pressures are required, as in advanced optic-disc damage or to improve corneal clarity. Angle surgery has lower success rates for secondary childhood glaucomas compared to PCG,2,3 so it can be considered as a procedure of choice for many secondary glaucomas. Contraindications for trabeculectomy include phakia/pseudophakia, the presence of a cataract that might need removal in the near future, and corneal pathology that might require transplantation in the near future.

Technique

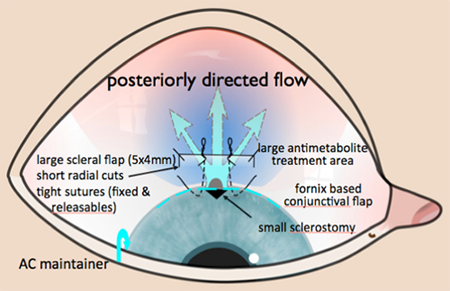

Traditionally, trabeculectomy in children was associated with significant complications largely related to early hypotony and adverse bleb morphology i.e. cystic, avascular blebs. These and other challenges of pediatric trabeculectomy, stimulated the re‑evaluation of the technique. There are many ways to perform trabeculectomy surgery in children, but Moorfield's Safer Surgery System (MSSS),4 which introduced simple modifications to the technique, and intraoperative application of Mitomycin C (MMC) have been found to encourage diffuse bleb formation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Contemporary pediatric trabeculectomy: Moorfield's Safer Surgery System.

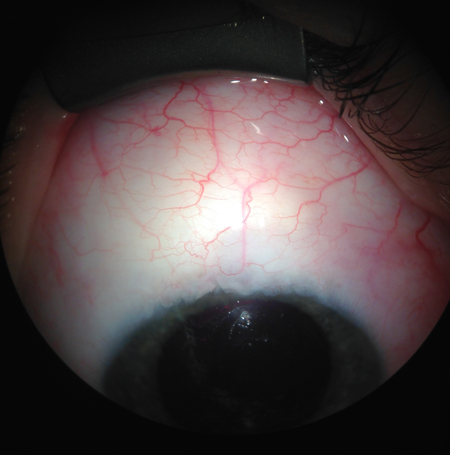

The MSSS emphasises a large area of treatment with antiscarring agent and posterior flow through a fornix based conjunctival flap and short scleral flap radial incisions to achieve posterior flow and a diffuse bleb (Figure 2).5,6

Figure 2. Diffuse, elevated bleb with contemporary surgical trabeculectomy technique.

"Titration" of postoperative intraocular pressure (IOP) is possible with releasable/adjustable sutures. This technique has been shown in adults and infants to be associated with favorable bleb morphology, reduced complications, and satisfactory outcomes.6,7 Buphthalmic eyes are especially prone to hypotony, flat anterior chambers, choroidal effusions, and suprachoroidal hemorrhage due to low scleral rigidity if aqueous flow is not well controlled. Measures to minimize hypotony are essential in trabeculectomy surgery especially in cases such as aniridia and Sturge Weber syndrome. For example, we recommend an anterior chamber (AC) maintainer to minimize any period of intraoperative hypotony and also to facilitate the accurate judgement of flow through the scleral flap.

Postoperative Management

Just as in adults, trabeculectomy requires frequent postoperative review to monitor the presence and degree of bleb inflammation. Potentially intensive steroid topical therapy might be required, which can be challenging for caregivers who might have difficulty gaining co-operation from young children. Additionally caregivers need to commit to frequent visits to the ophthalmologist for postoperative monitoring, which affects the child's schooling and potentially the caregiver's ability to commit to work or care for the rest of the family.

The surgeon's challenges include adequate examination of the child and the ability to perform postoperative manipulations such as suture removal or application of further antiscarring agent. Examinations under anaesthesia (EUA) might be required for this purpose, often on a repeated basis. Remember that IOP measurement can be inaccurate with inhalational anesthetics, which reduce IOP.

Failure tends to occur early in children, so frequent monitoring in the early postoperative period is vital. Examine children the first postoperative week and then weekly for the first month followed by greater intervals depending on bleb appearance and IOP control. In infants, at least 1 EUA is required within the first month after surgery preferably within the first 2 weeks. While under anaesthesia, you can take the opportunity to manipulate or remove sutures, inject subconjunctival 5Fluorouracil (5FU, 0.2–0.3 ml of 50 mg/ml 5FU), and to inject steroids such as betamethasone and local anesthetic adjacent to the bleb. Adjust topical steroids depending on the degree of inflammation and IOP, and in general, follow a weaning regimen for 3–4 months.

Success and Complications

Trabeculectomy is more likely to fail in children than adults8,9 due to the child's more vigorous wound healing.10 This propensity to failure necessitates using MMC, which you can use at varying potencies and requires only intraoperative exposure, a major advantage over 5FU in children. However, MMC is associated with higher complication rates. Early complications relate to hypotony (shallow or flat AC), hypotony maculopathy, choroidal effusion, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, and late complications are associated with thin, avascular, cystic blebs prone to leakage and potentially blinding infection.11–16

The potential for complications after trabeculectomy, especially with MMC, cannot be overstated in children. The most appropriate MMC dose and duration of exposure for children is unknown, but most surgeons use 0.2–0.5 mg/ml depending on the number of risk factors for scarring and familiarity with specific concentrations. If an avascular cystic bleb develops, inform parents of the risk and seriousness of bleb-related infection. Advise them to report immediately to an ophthalmologist if symptoms or signs of bleb-related infection occur.

With MMC, trabeculectomy cumulative success rates of 59%–90% at 2 years reducing to 51% at 5 years have been reported.12,14,17 Compared to GDDs, trabeculectomy surgery can achieve lower mean IOP,12 depend less on medication for IOP control,6,12,18 and require less postoperative surgical revision.18,19

A reported risk factor for trabeculectomy failure, even with MMC, is glaucoma following congenital cataract surgery.12,20,21 Furthermore, success in infants, especially in those younger than 1 year, has been reported to be lower than older age groups11,13,16 and when compared to glaucoma drainage implants (GDDs).19 However, a more recent study suggests that with appropriate case selection (phakic patients) and regular follow-up, success can be comparable to GDDs.6 When trabeculectomy fails to control IOP, you can try bleb needling with an antiscarring agent if the bleb architecture allows and the sclerostomy is patent. You can repeat trabeculectomy with a stronger dose of MMC or consider a GDD if further surgery is required.

References

- Cairns JE. Trabeculectomy. Preliminary report of a new method. Am J Ophthalmol 1968;66: 673-679.

- Luntz MH. Congenital, infantile, and juvenile glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1979; 86: 793-802.

- Rice NSC. The surgical management of congenital glaucoma. Aust J Ophthalmol 1977;5:174-9.

- Khaw PT, Chiang M, Shah P, Sii F, Lockwood A, Khalili A. Enhanced Trabeculectomy – The Moorfields Safer Surgery System. In Glaucoma Surgery. Dev Ophthalmol. Bettin P, Khaw PT (eds) Basel: Karger, 2012: vol 50, pp 1-28.

- Papadopoulos M, Edmunds B, Chiang M, Mandal A, Grajewski AL, Khaw PT. Glaucoma surgery in children. In: Weinreb RN, Grajewski A, Papadopoulos M, Grigg J, Freedman S. (editors) Childhood Glaucoma. WGA Consensus Series - 9. Amsterdam: Kugler Publications; 2013, pp 95-134.

- Jayaram H, Scawn R, Pooley F, et al. Long Term Outcomes of Trabeculectomy Augmented with Mitomycin-C Undertaken within the First Two Years of Life. Ophthalmology 2015;-:1-7

- Wells AP, Cordeiro MF, Bunce C, Khaw PT. Cystic bleb formation and related complications in limbus- versus fornix-based conjunctival flaps in pediatric and young adult trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Ophthalmology 2003;110(11):2192-7.

- Gressel MG, Heuer DK, Parrish RK, 2nd. Trabeculectomy in young patients. Ophthalmology 1984;91(10):1242-6.

- Inaba Z. Long-term results of trabeculectomy in the Japanese: an analysis by life-table method. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1982;26(4):361-73.

- Beauchamp GR, Parks MM. Filtering surgery in children: barriers to success. Ophthalmology 1979;86(1):170-80.

- Susanna R Jr, Oltrogge EW, Carani JC, Nicolela MT. Mitomycin as adjunct chemotherapy with trabeculectomy in congenital and developmental glaucomas. J Glaucoma 1995; 4:151-157.

- Beck AD, Wilson WR , Lynch MG, et al. Trabeculectomy with adjunctive mitomycin C in pediatric glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 1998; 126: 648-657.

- Freedman SF, McCormick K, Cox TA. Mitomycin C-augumented trabeculectomy with postoperative wound modulation in pediatric glaucoma. J AAPOS 1999; 3: 117-124.

- Sidoti PA, Belmonte SJ, Liebmann JM, Ritch R. Trabeculectomy with mitomycin-C in the treatment of pediatric glaucomas. Ophthalmology 2000; 107: 422-429.

- Waheed MD, Ritterband DC, Greenfeld DS, et al. Bleb-related ocular infection in children after trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Ophthalmology 1997;104:2117–2120.

- Al-Hazmi A, Zwaan J, Awad A, et al. Effectiveness and complications of MMC use during pediatric glaucoma surgery. Ophthalmology 1998; 105: 1915–1920.

- Giampani J Jr, Borges-Giampani AS, Carani JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of trabeculectomy with mitomycin C for childhood glaucoma: a study of results with long-term follow-up. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2008;63:421-6.

- Chen TC, Chen PP, Francis BA, et al. Pediatricglaucoma surgery: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2014 Nov;121:2107-15.

- Beck AD, Freedman S, Kammer J, Jin J. Aqueous shunt devices compared to trabeculectomy with mitomycin C for children in the first two years of life. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136: 994-1000.

- Mandal AK, Bagga H, Nutheti R, et al. Trabeculectomy with or without mitomycin-C for pediatric glaucoma in aphakia and pseudophakia following congenital cataract surgery. Eye 2003;17:53-62.

- Azuara-Blanco A, Wilson RP, Spaeth GL, et al. Filtration procedures supplemented with mitomycin C in the management of childhood glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83: 151-156.