Researchers from the University of Liverpool have discovered that an estimated 15% of Ebola survivors have a retinal scar that appears specific to the disease.

“The distribution of these retinal scars or lesions provides the first observational evidence that the virus enters the eye via the optic nerve to reach the retina in a similar way to West Nile virus. Luckily, they appear to spare the central part of the eye so vision is preserved,” said Paul Steptoe, MD, an ophthalmologist at the Royal Liverpool Hospital who performed the ocular examinations. “Our study also provides preliminary evidence that in survivors with cataracts causing reduced vision but without evident active eye inflammation (uveitis), aqueous fluid analysis does not contain Ebola virus therefore enabling access to cataract surgery for survivors.”

The study, published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, assessed survivors discharged from the Ebola Treatment Unit at the 34th Regiment Military Hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Using an ultra-widefield retinal camera, Dr. Steptoe and his team examined 82 Ebola survivors who had previously reported ocular symptoms, and 105 unaffected controls from civilian and military personnel.

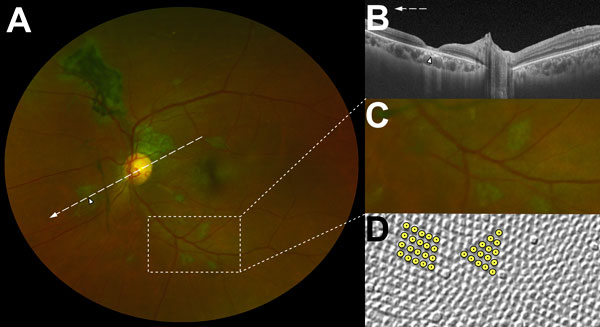

Though lesion shape varied among post-Ebola eyes, they all shared an angular shape—often resembling a diamond or wedge—that is uncharacteristic of any other retinal disease. The authors hypothesize that the sharp appearance of these lesions may be due to the tight triangular packing of the retinal cone mosaic.

Characteristic features of lesions observed in a case–control study of ocular signs in Ebola virus disease survivors. A) Composite scanning laser ophthalmoscope retinal image, left eye. Arrow indicates direction of the optical coherence tomography scan. B) Optical coherence tomography. White, long, dashed line indicates cross-sectional plane; white arrowhead indicates Ebola lesion limited to the retinal layers with an intact retinal pigment epithelium. C) Examples of straight-edged, sharp angulated lesions D) Example of tangential section through the human fovea with illustrative highlighting of a triangular photoreceptor matrix corresponding to Ebola lesional shape.

OCT revealed that the lesions were limited to the retina and located either adjacent to the optic disc or in the fundus periphery. Despite the proximity to the optic nerve head (ONH) in 8 cases, the area showed no swelling or pallor.

Analyzing photos of these ONH-bordering lesions, the team observed curvilinear projections from the disc margin that appear to align with the anatomic pathway of the retinal ganglion cell axons that constitute the optic nerve. This distribution suggests a neurotrophic spread into the eye from the optic nerve and along retinal ganglion cell axons. The authors note another possible mode of entry into the eye is hematologic.

Fortunately, the retinal lesions did not affect vision. Researchers found no difference in uncorrected visual acuity found between Ebola survivors and controls. And despite concerns over the safety of cataract surgery in Ebola survivors, the authors showed that the virus does not necessarily persist in the aqueous humor. Samples from 2 survivors with white cataract and no anterior chamber inflammation were negative for Ebola RNA on PCR assay.

Although the sample size was too small to make any definitive conclusions, the findings raise the possibility of safe cataract surgery for Ebola survivors with no signs of ongoing intraocular inflammation.